In case you didn’t know, the huge silver building glinting in the sunshine just off the A34, is not a giant UFO or spaceship, but Diamond Light Source. It’s the UK’s national synchrotron, and an amazing resource for science in both the UK and further afield.

Based close to the Ridgeway, on the Harwell Campus, it is keeping the UK at the forefront of global scientific research and discovery. It creates a super-bright light 10 billion times brighter than the sun, which enables scientists to break new science frontiers by making the invisible visible. Indeed, since beginning operations in 2007, experiments at Diamond have resulted in the publication of over 7000 scientific papers detailing important and often groundbreaking new discoveries.

Roughly the footprint of Wembley Stadium and with a half-kilometre circumference, Diamond is a huge scientific machine which works like a giant microscope, harnessing the power of electrons to produce light, which is channeled into 32 laboratories known as ‘beamlines’. These very intense beams of x-rays, infrared and ultraviolet light can be used to support an astonishing variety of research. Scientists use the light to study everything from fossils and historical artefacts to new medicines and treatments for disease, pollution and climate change to innovative engineering, new energy sources and cutting-edge technology.

Making the invisible visible

For centuries, scientists have used microscopes to study things that are too small to see with the naked eye. However, microscopes are limited by the visible light that they use. To study smaller objects like molecules and atoms, scientists need to use the special light generated by the synchrotron. Whether it’s fragments of ancient paintings or unknown virus structures, at Diamond, scientists can study their samples using a machine that is 10,000 times more powerful than a traditional microscope.

Diamond is one of the most advanced scientific facilities in the world, and it is run as a not-for-profit limited company, funded as a joint venture by the UK government, through the Science & Technology Facilities Council (STFC) in partnership with the Wellcome Trust. The synchrotron is free at the point of access through a competitive application process, provided that the results are in the public domain. Over 7000 researchers from both academia and industry use Diamond to conduct experiments, assisted by approximately 600 staff.

Tackling plastic pollution – engineering a plastic-digesting enzyme

Scientists working with Diamond have recently engineered an enzyme which can digest some of our most commonly polluting plastics, providing a potential solution to one of the world’s biggest environmental problems.

The discovery could result in a recycling solution for millions of tonnes of plastic bottles, made of polyethylene terephthalate, or PET, which currently persists for hundreds of years in the environment.

The research was led by teams at the University of Portsmouth and the US Department of Energy’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) and is published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). They solved the crystal structure of PETase – a recently discovered enzyme that digests PET – and used this information to understand how it works. During this study, they inadvertently engineered an enzyme that is even better at degrading the plastic than the one that evolved in nature.

The researchers are now working on improving the enzyme further to allow it to be used industrially to break down plastics in a fraction of the time. Professor John McGeehan said: “Diamond recently created one of the most advanced x-ray beamlines in the world and having access to this facility allowed us to see the 3D atomic structure of PETase in incredible detail. Being able to see the inner workings of this biological catalyst provided us with the blueprints to engineer a faster and more efficient enzyme.”

The researchers found that the PETase mutant was better than the natural PETase in degrading PET. Significantly, the enzyme can also degrade polyethylene furandicarboxylate, or PEF, a bio-based substitute for PET plastics that is being hailed as a replacement for glass beer bottles.

The results achieved will be invaluable in tailoring the enzyme for use in large-scale industrial recycling processes. The impact of such an innovative solution to plastic waste could be global.

Henry VIII’s “Balls” – Ironshot from the Mary Rose

Humans have been using iron to make weapons, tools and ceremonial items for more than 20,000 years, but once these objects have been excavated they are at risk from corrosion. Each recovered artefact has to be conserved to prevent it from deteriorating in the presence of air and water. Until now, a comparison of the effectiveness of different conservation methods has been hampered by the variable nature of the artefacts found, and the environments in which they were buried.

When King Henry VIII’s flagship, the Mary Rose, sank off Portsmouth in 1545, it took with it 1248 iron cannonballs. Seawater and iron are not compatible, causing corrosion that eats away at the metal and weakens its structure. Since the excavation of the shipwreck, the cannonballs have been conserved in different ways. Dr Eleanor Schofield, head of conservation at the Mary Rose, working with PhD student Hayley Simon from UCL Institute of Archaeology and Diamond, is using many of its non-destructive techniques available to unlock the secrets of ancient treasures and explore ways to conserve artefacts.

Diamond’s bright light x-rays make it possible to visualise the differences in the corrosion profiles and trace them to the treatments applied. Already much has been achieved through the research carried out at Diamond on the wood from the main ship, monitoring its treatment and current display environment and developing new conservation treatments.

Synchrotron x-ray techniques can differentiate iron corrosion products formed during treatments, even years later, giving us an unprecedented insight into the effects of conservation techniques on iron corrosion. This new information will play an important role in future conservation developments concerning archaeological iron worldwide.

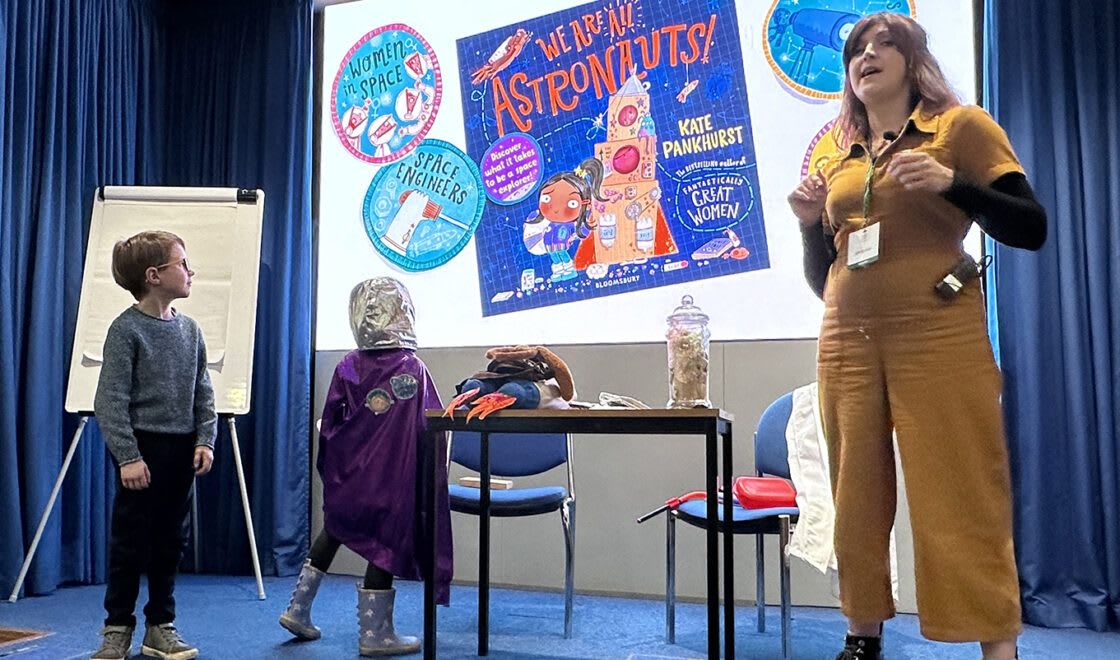

Inspiring young engineers and scientists

As one of the most exciting places in the country to be a scientist or engineer, Diamond is on a mission is to share this excitement with young people. However, skills shortages in STEM (science, technology, engineering and maths) mean the scientists and engineers needed to run and develop the UK’s synchrotron may not be available if current trends continue. New generations of scientists are needed to research solutions to global problems and create the technological advancements that are the lifeblood of a modern economy.