He sat among the woods; he heard

The sylvan merriment; he saw

The pranks of butterfly and bird,

The humours of the ape, the daw.

And in the lion or the frog,—

In all the life of moor and fen,—

In ass and peacock, stork and dog,

He read similitudes of men.

Taken from Aesop (Andrew Lang) (1844-1912)

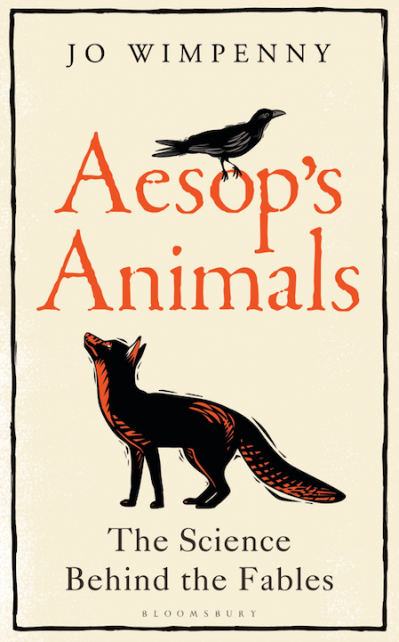

Many of us grew up with Aesop’s fables, believing that the fox is clever, the donkey is foolish and the wolf is the villain of the piece. From these ancient stories we learned moral lessons, but we also grew up to believe that certain animals behave in certain ways. In a new book, Aesop’s Animals: the Science behind the Fables, author Jo Wimpenny considers several of Aesop’s animal characters, asking whether what we think we know matches up with reality. Does science support the preconceptions that have been built into our brains through these childhood stories?

Many of us grew up with Aesop’s fables, believing that the fox is clever, the donkey is foolish and the wolf is the villain of the piece. From these ancient stories we learned moral lessons, but we also grew up to believe that certain animals behave in certain ways. In a new book, Aesop’s Animals: the Science behind the Fables, author Jo Wimpenny considers several of Aesop’s animal characters, asking whether what we think we know matches up with reality. Does science support the preconceptions that have been built into our brains through these childhood stories?

We spoke with Wimpenny, a zoologist-turned-writer with a research background in animal behaviour and the history of science. She studied Zoology at the University of Bristol and went on to research problem-solving in crows at the University of Oxford.

Animals have been a lifelong interest of mine, I grew up in the countryside where there was nature everywhere, and we had cats, dogs, and hamsters. Even as a child I wasn’t just interested in spotting different animals: I wanted to know why they were doing what they were doing. I guess going on to study zoology was pretty much a given.

As a student I heard about a pivotal study in which a New Caledonian crow called Betty bent a wire to make a hook so that she could retrieve a treat. That blew my mind! It was such incredible problem-solving and inspired me to join the research team studying these crows’ behaviour as a DPhil student. Although New Caledonian crows became something of a ‘poster child’ of bird intelligence, the whole corvid family – which includes rooks, ravens, jackdaws and more – is fascinating. I know that some of them, like magpies, have a bad reputation as bullies and thieves, but there’s such a glint in their eyes and the way they stalk is so characterful that I can’t help but wonder what’s going on in their heads. These days, the term ‘bird-brained’ should really be used as a compliment.

While I was working on crows, two researchers in Cambridge – the aptly-named Chris Bird and his PhD supervisor, Nathan Emery – published a study which showed that rooks could use stones to raise the water level in a glass (so that they could reach a floating worm) just as the crow did in Aesop’s fable of The Crow and The Pitcher:

A crow perishing with thirst saw a pitcher, and hoping to find water, flew to it with delight. When he reached it, he discovered to his grief that it contained so little water that he could not possibly get at it. He tried everything he could think of to reach the water, but all his efforts were in vain. At last, he collected as many stones as he could carry and dropped them one by one with his beak into the pitcher, until he brought the water within his reach and thus saved his life.

Aesop is thought to have been an ancient Greek storyteller who lived some 2,500 years ago, and today this fable has been replicated by modern science. Had he known that corvids could do this? Could he have even seen it happen? It got me thinking whether any of his other fables had any basis in fact, and that was the whole starting point for Aesop’s Animals.

Whereas Aesop depicted crows as clever, another of his fables is about a thirsty pigeon who saw a goblet of water painted on a signboard. Not realising it was only a picture, she flew towards it and crashed into the sign. The impact broke her wings and, falling to the ground, she was caught by one of the bystanders. And yet, science tells us that pigeons actually have fantastically good vision and discriminative abilities, including being able to tell apart cancerous and normal cells from medical images. While the pigeon fable didn’t make it into the final manuscript, it did make me want to shine a light on the underdogs – the animals that are typically misrepresented in these stories.

One of the animals that has been sadly maligned in Aesop’s fables, and many stories since, is the wolf. We have all grown up with the traditional tales of the Three Little Pigs and Red Riding Hood. On TV, and in movies, they’re often cast as evil villains, waiting in the dark to pounce on the unsuspecting. Generations of children have grown up to fear an animal because they believe it to be an evil, villainous murderer. These are very human terms and they’re tied up with human notions of intentionality; they’re not relevant to describe other animals. Wolves are one of most feared and persecuted animals on the planet, yet they are the closest living relatives of our familiar animal companions, the dog, with whom they share 99.9% of their genes. They’re wild carnivores so they hunt because they need to survive, not because they’re evil. And, they actually have to work very hard for their food – research has found that on average, they only make a kill in 14% of their attempted hunts, and typically they end up picking off the weak, sick or injured animals from a herd. Wolves are also often depicted as loners, and yet for most of their lives they live in strongly bonded family groups. They are loyal, playful, intelligent animals – many of the traits that we strongly value in our own species. Yes, wolves can be dangerous to us, but that comes down to their biology as a wild predator rather than any ingrained malevolence.”

One of the animals that has been sadly maligned in Aesop’s fables, and many stories since, is the wolf. We have all grown up with the traditional tales of the Three Little Pigs and Red Riding Hood. On TV, and in movies, they’re often cast as evil villains, waiting in the dark to pounce on the unsuspecting. Generations of children have grown up to fear an animal because they believe it to be an evil, villainous murderer. These are very human terms and they’re tied up with human notions of intentionality; they’re not relevant to describe other animals. Wolves are one of most feared and persecuted animals on the planet, yet they are the closest living relatives of our familiar animal companions, the dog, with whom they share 99.9% of their genes. They’re wild carnivores so they hunt because they need to survive, not because they’re evil. And, they actually have to work very hard for their food – research has found that on average, they only make a kill in 14% of their attempted hunts, and typically they end up picking off the weak, sick or injured animals from a herd. Wolves are also often depicted as loners, and yet for most of their lives they live in strongly bonded family groups. They are loyal, playful, intelligent animals – many of the traits that we strongly value in our own species. Yes, wolves can be dangerous to us, but that comes down to their biology as a wild predator rather than any ingrained malevolence.”

In Aesop’s Animals, Jo considers a range of animals to unpick the data, explore the latest research and examine the evidence for tool use, self-recognition, imitation, cooperation, deception and the ability to plan for the future. She asks whether Aesop chose the best animals for each of his stories, or whether some have been miscast. Is the wolf capable of deception or would another animal be better ‘in sheep’s clothing’? Could a slow-and-steady tortoise really beat a scatter-brained hare in a race? Who would you have backed?

Another of the fables in the book is The Ants and the Grasshopper, in which the grasshopper spends the whole of a fine summer dancing and singing and not doing anything useful at all, while his neighbours, the ants, are working tirelessly to stash grain for the winter. When the winter comes the hungry grasshopper begs for food, but the ants send him away, chastising him for his frivolity while the sun shone. This leads into the question of whether animals can actually think ahead. It’s long been thought that animals exist only in the present cognitively; however, there is evidence from apes, corvids and others that they can think about events in the past and plan ahead for the future, something called ‘mental time travel’. Ants show a lot of complex behaviours that certainly look like they’re planning for future, including storing up grain for the winter. But, just like birds migrating or bears hibernating, they’re not doing this because each individual is thinking ahead and predicting the challenges of winter. This is very different to the way in which we plan, for example by booking a holiday several months ahead. During their growth and development, hermit crabs go off to seek a new shell but are they browsing and considering in the same way we would choose a new house? Almost certainly not.

To find out more about the truth behind the fables, visit Animal fables: fact or fiction? Waterstones bookshop, on Tuesday 11 October at 6.30pm.

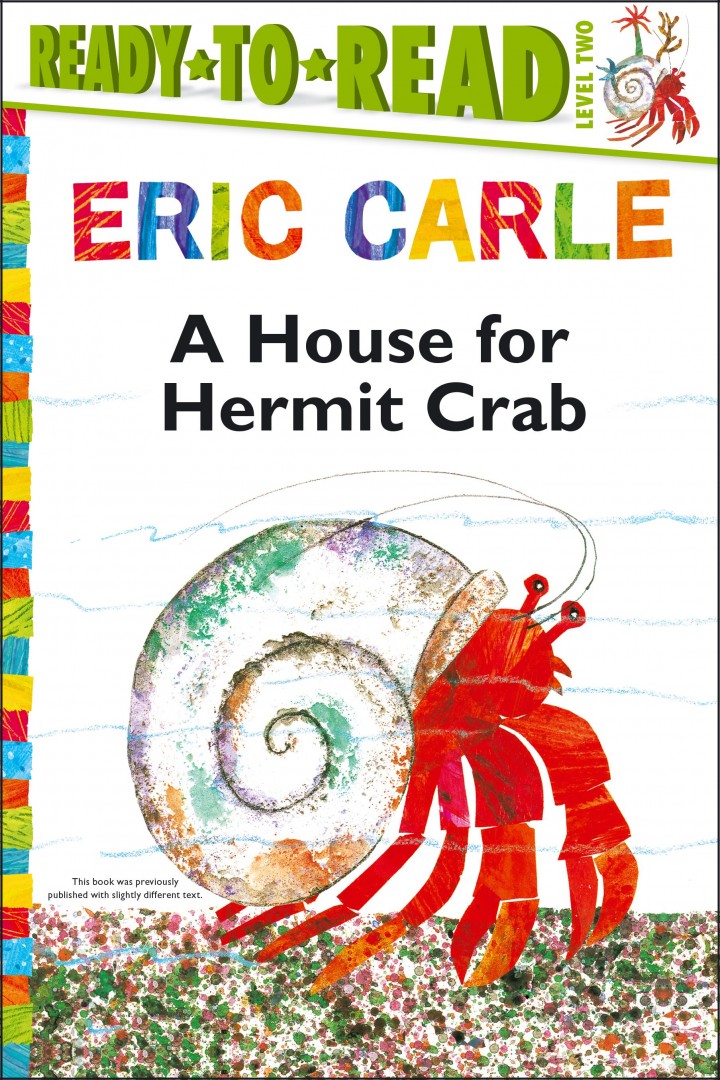

Eric Carle’s A House for Hermit Crab ⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️⭐️

Eric Carle’s picture book A House for Hermit Crab tells a story of a crab who moves into a rather dull shell and decides, month by month, to invite the creatures he encounters under the sea to live on his shell. What will happen when Hermit Crab outgrows this shell at the end of the year?

Eric Carle’s picture book A House for Hermit Crab tells a story of a crab who moves into a rather dull shell and decides, month by month, to invite the creatures he encounters under the sea to live on his shell. What will happen when Hermit Crab outgrows this shell at the end of the year?

This is a lovely story, especially for children who are facing change in their own lives as it broaches issues of growth, change, and embracing a new future and the exciting possibilities that lie ahead.

Carle’s bright painted and collaged illustrations are instantly recognisable by anyone who knows The Very Hungry Caterpillar, and through the book show the delightful variety of the marine creatures in cheerful colours. They also illustrate the symbiotic relationship between species on the ocean floor.

It’s also a great way to get children thinking about the judgements we make within these pages about each animal’s character. Hermit Crab seems smart, welcoming and optimistic. Carle’s anemone looks as pretty and gentle as a garden flower, but in the real world a sea anemone protects the hermit crab from predators with its long stinging threads. The spiky sea urchin looks fierce: will it join the animals decorating the shell?

You can explore these ideas and other picture books that have animal behaviour at their heart with storyteller Sarah Law at Oxfordshire County Library on Saturday 8 October.