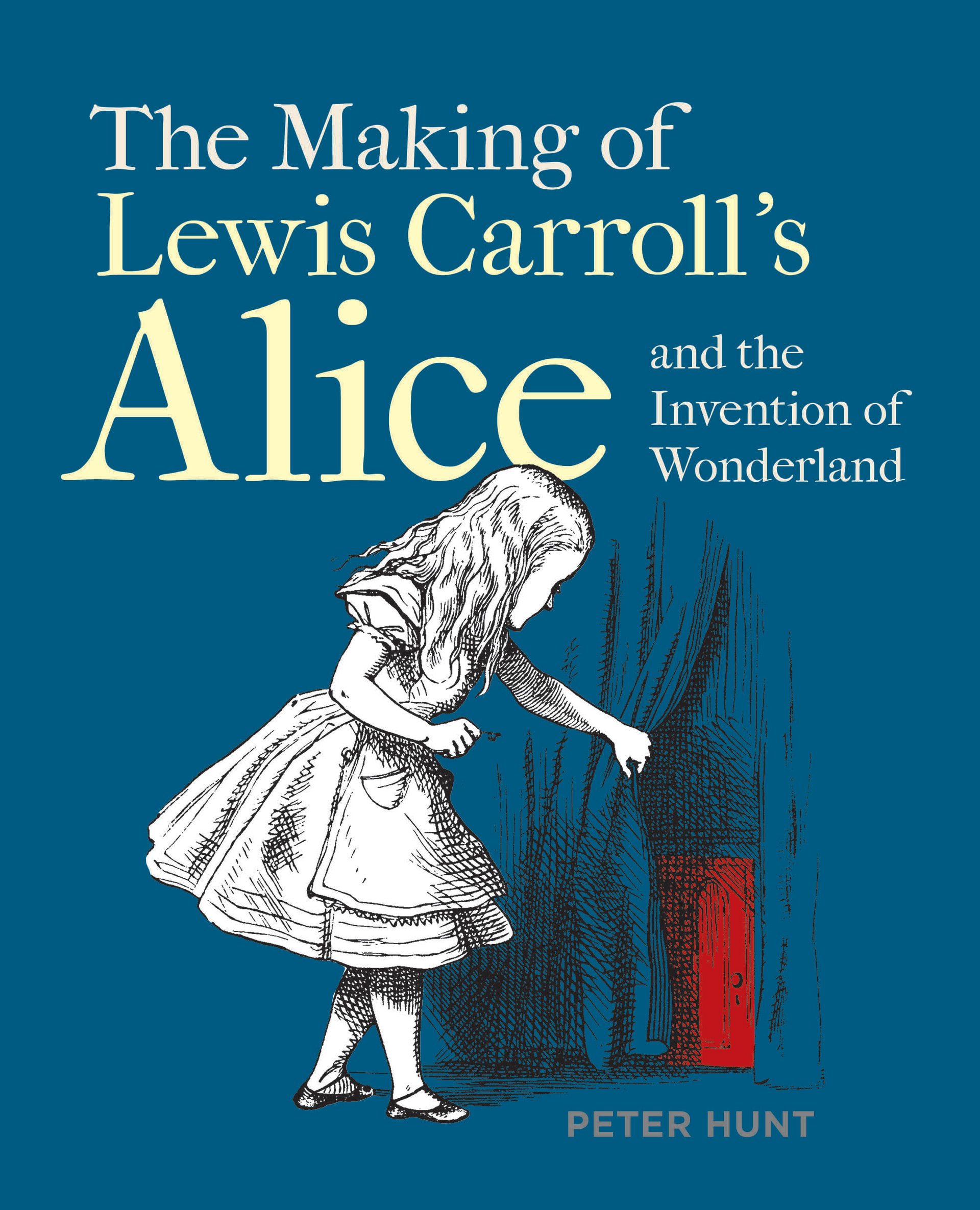

Books about Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (AKA Lewis Carroll), says Peter Hunt, tend to focus on his sexuality and the nature of his relationship with Alice Liddell – the young girl for whom the mathematician originally devised the ‘Alice’ stories – “the gossip really”. In penning his own book on Dodgson, The Making of Lewis Carroll’s Alice and the Invention of Wonderland, Hunt “didn’t want to go anywhere near that again”. It’s all conjecture, he says, with critics tying themselves in knots trying to explain whether or not the Oxford lecturer was a paedophile. “I thought, let’s not do that, let’s look somewhere else to account for why he’s so interesting.” He did have lots of ‘child-friends’ though, why was that? He was a man who liked children, says Hunt, which sounds peculiar nowadays, but a 1946 Puffin  edition of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland is illustrative of standards shifting. Eleanor Graham’s foreword looks favourably upon the writer’s activities of pinning up little girls’ dresses at the seaside to prevent them getting wet, and taking a box of toys with him on the train in case he found himself sharing a carriage with a child. “In 1946,” he says, “that was regarded as being very jolly and totally innocent. Now, you think, ‘good God, what’s going on?’ There are fashions in what is regarded as being acceptable and not acceptable, and we tend to judge the past from the present, don’t we?” Liddell, daughter of the Dean of Christ Church, “was probably his favourite child of all time, but there were other contenders – later on he had young girls who were very fond of him and vice versa.” However, there are no recorded complaints about Dodgson from any children; somewhat odd, he points out, if his conduct wasn’t innocent.

edition of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland is illustrative of standards shifting. Eleanor Graham’s foreword looks favourably upon the writer’s activities of pinning up little girls’ dresses at the seaside to prevent them getting wet, and taking a box of toys with him on the train in case he found himself sharing a carriage with a child. “In 1946,” he says, “that was regarded as being very jolly and totally innocent. Now, you think, ‘good God, what’s going on?’ There are fashions in what is regarded as being acceptable and not acceptable, and we tend to judge the past from the present, don’t we?” Liddell, daughter of the Dean of Christ Church, “was probably his favourite child of all time, but there were other contenders – later on he had young girls who were very fond of him and vice versa.” However, there are no recorded complaints about Dodgson from any children; somewhat odd, he points out, if his conduct wasn’t innocent.

Was he a nice person? “I don’t think I would have liked him very much.” Dodgson was obsessive, he says, the kind of character he’d rather only see occasionally – though “probably quite charming when he wanted to be”. Macmillan once received a letter from the author, he says relaying his “favourite anecdote about the control freak side of his character”, instructing their post section how to wrap his books. “I’m not sure how well I would have got on with a guy like that,” he resumes, moving on to the relationship between Dodgson and his illustrator, John Tenniel. “Dodgson tried to get everything as he wanted it, Tenniel was clearly quite a distinguished guy, he wasn’t used to being kicked around. I think Dodgson was very lucky Tenniel actually illustrated Through the Looking-Glass at all because he was probably fed up with him by then.”

The books are also lacking nice characters which, he says, makes you wonder why the ‘Alice’ stories are so popular. You might expect books that stand the test of time to comprise  people with whom readers empathise (he mentions Heidi and Winnie the Pooh) but such people don’t seem to exist in Dodgson’s tales, in which even the title character is “quite cold”. One of the mysteries, he states, surrounding their longevity.

people with whom readers empathise (he mentions Heidi and Winnie the Pooh) but such people don’t seem to exist in Dodgson’s tales, in which even the title character is “quite cold”. One of the mysteries, he states, surrounding their longevity.

The books have indeed become so entrenched in our culture that “every day I bet you could find in a newspaper a headline that says, ‘this is a Wonderland situation’, ‘politics of Wonderland’, or something like that.” Most people haven’t read them and yet we’re all aware of them. There’s no going back, he says, once a book boasts 7,000 editions worldwide. “You could say it’s the old snowball effect; it’s a classic because it’s a classic and therefore it continues to be a classic.” Tim Burton’s 2010 film, he resumes, bears little resemblance to the work of Lewis Carroll, yet sold on the name. It’s also made its way into the public consciousness “without the help of Disney, the Disney film isn’t very important in the transmission of ‘Alice’.”

Hunt has also written The Making of The Wind in the Willows, which required more original research. The author upon which it focuses was a very different character to Dodgson, also  “a shrewd businessman” who wrote 2,000 letters a year. “Kenneth Grahame was basically the laziest man you’ve ever met in your life. Dodgson produced more in about ten minutes than Grahame did in his lifetime.” The latter married well and had a very good job at the Bank of England, he says, which he “left under strange circumstances. He was sort of conned into writing Wind in the Willows,” he says, “otherwise he wouldn’t have written anything – you can’t imagine him sitting down and writing 2,000 letters a year.”

“a shrewd businessman” who wrote 2,000 letters a year. “Kenneth Grahame was basically the laziest man you’ve ever met in your life. Dodgson produced more in about ten minutes than Grahame did in his lifetime.” The latter married well and had a very good job at the Bank of England, he says, which he “left under strange circumstances. He was sort of conned into writing Wind in the Willows,” he says, “otherwise he wouldn’t have written anything – you can’t imagine him sitting down and writing 2,000 letters a year.”

Well if you will write them about minor things like packaging, you’ll likely hit a high number.

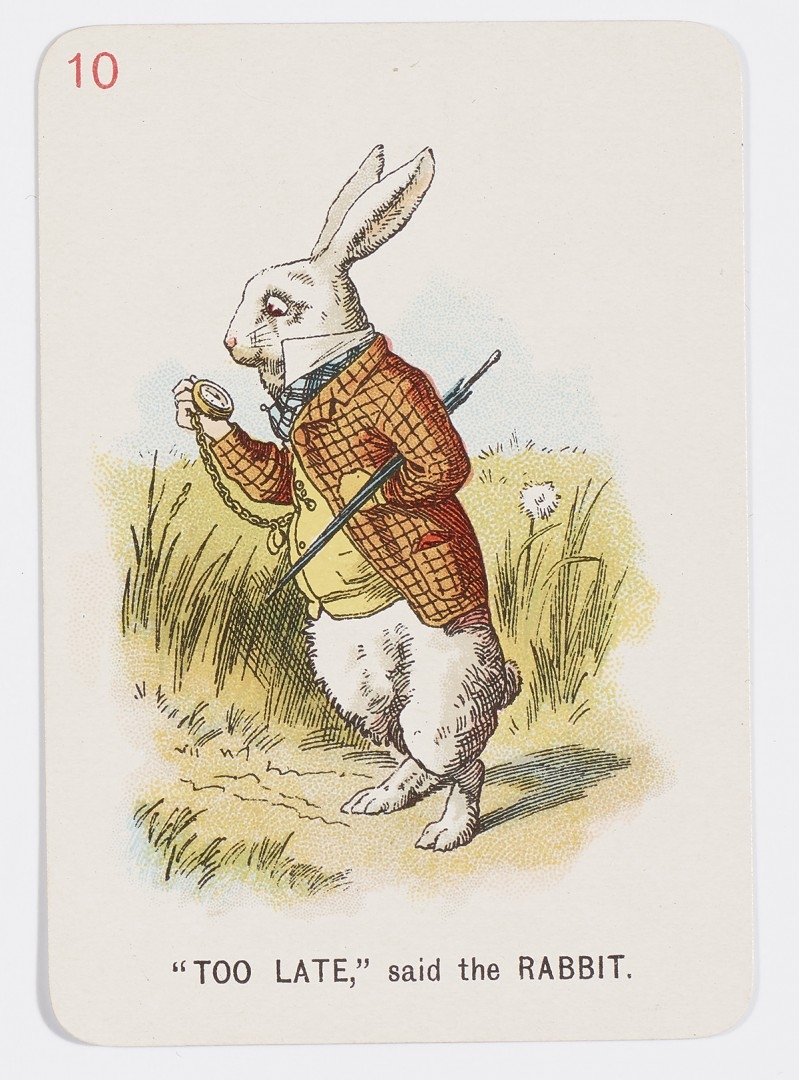

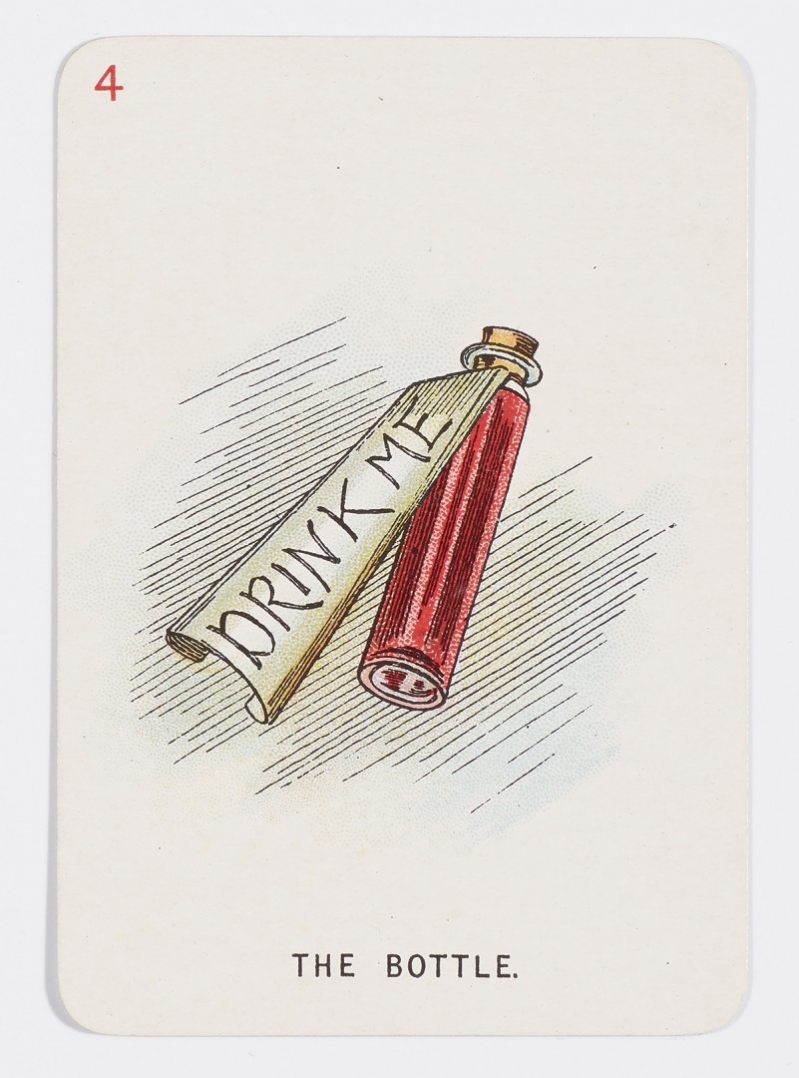

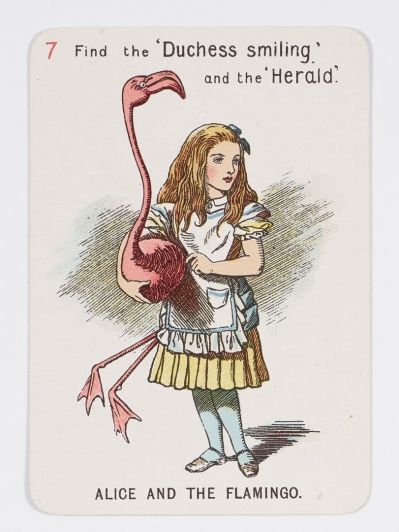

All images credited to the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford, 2020

The Making of Lewis Carroll’s Alice and the Invention of Wonderland is available from bodleianshop.co.uK