The Beyond the Binary project aims to shape Pitt Rivers into a welcoming space, so that no individual or group feels excluded because of sexuality or gender, and all visitors – however they might identify – can understand humanity better. Beyond the Binary is working with a broad range of partners to challenge historical interpretations of the museum’s collections, offering alternative understandings from people with different identities, as well as identifying human histories which are unrepresented as a result of intolerance. Losing Venus, consisting of multiple installations by Matt Smith, highlights the colonial impact on LGBTQ lives across the British Empire. From his house during lockdown, the artist spoke to Sam Bennett about a captain’s love quest, by which ways of loving were erased.

I do appreciate you taking the time to talk to me in these uncertain times.

To be honest, any excitement at the moment is great so don’t worry at all.

To COVID-19 matters first then, what does the current situation mean for you as an artist, with museums and galleries closing?

I’ve been really lucky, the timings of projects have meant I’ve managed to get stuff onto the radar, but then I’ve got a show in the summer that’s just been delayed indefinitely. Sort of like everybody, there are things that are really awkward, but it’s also a relief to have a bit of time to sort stuff out. What’s lovely is everybody’s found their humanity again, and we’ve all realised that stuff goes wrong.

The virus means people won’t see Losing Venus in the flesh for a bit, but let’s get them excited for when they can.

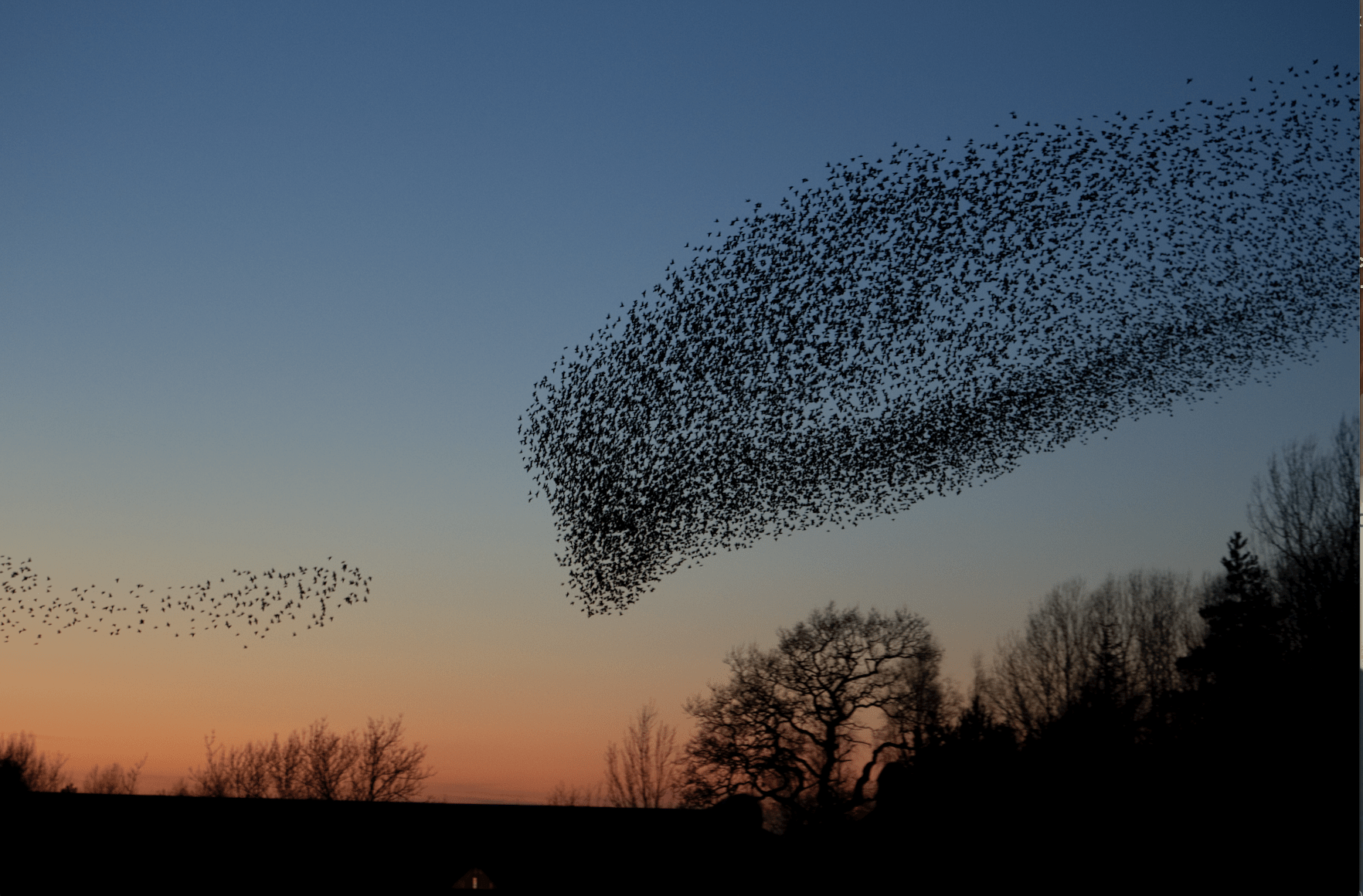

I remember Bird la Bird, a performance artist, showing two maps: one of the British Empire around 1920 and one of countries where it’s still illegal to be LGBTQ. They don’t match exactly but there’s a lot of overlap between the two, and I was interested. I’ve been waiting for the right time to try and unpick it a bit. When the Pitt Rivers said they were interested in working together it seemed like a good opportunity. The museum is really good at documenting what people wore or what they used, but museums tend to be less good at talking about people’s emotions or lives. The one place where the museum has evidence of people is in their photographic collection. So, I was interested in going through that and looking at countries where LGBTQ people were discriminated against through British legislation during the Empire, and taking some of those images out and replacing the actual people with a gridded system, to talk about this loss of knowledge that is inherent in museums.

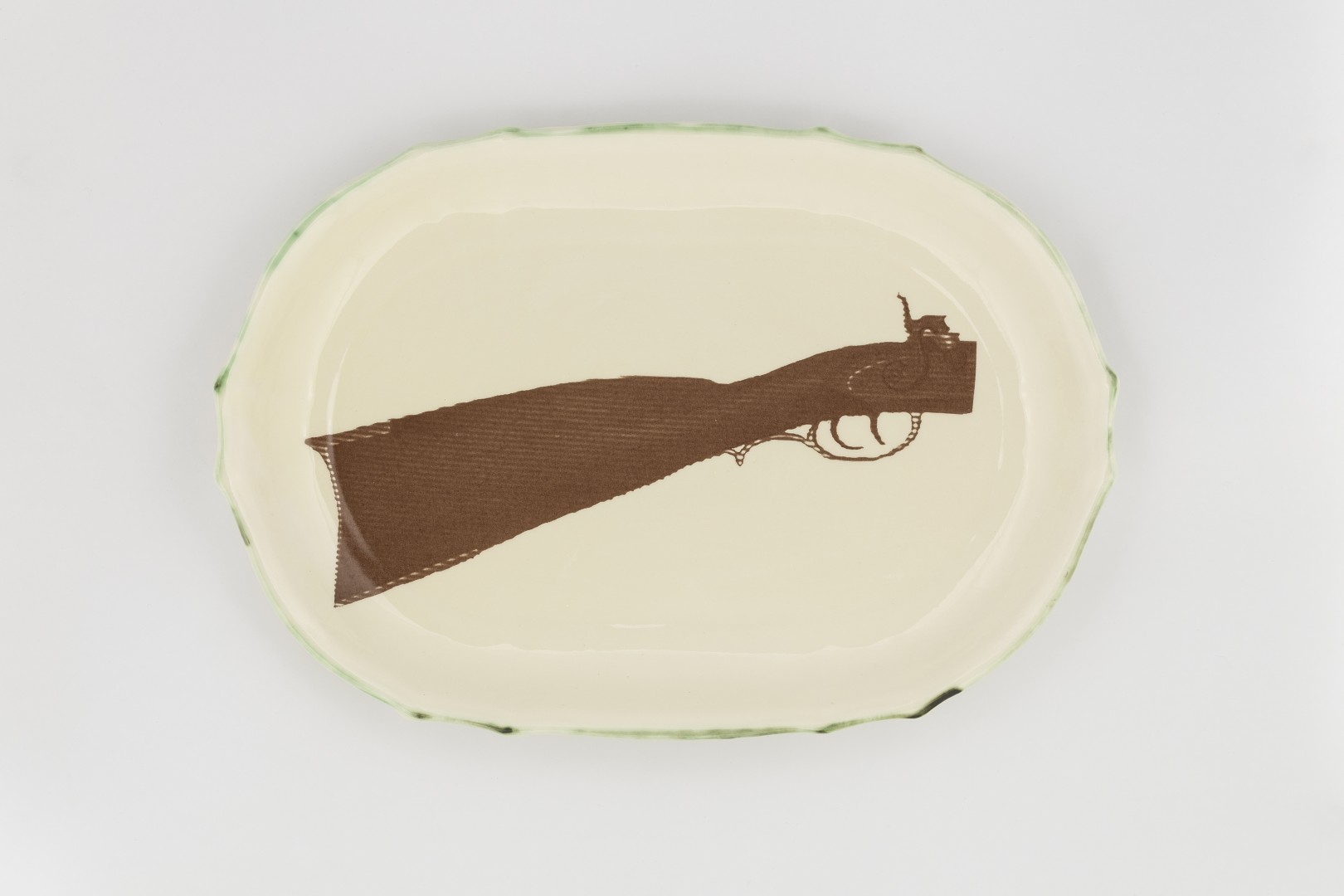

That was the starting point, and then it was like, how do we move back? I was interested in the journey of Captain Cook 250 years ago, ostensibly to map the transit of Venus in Tahiti. By looking at the movement of the planet from Tahiti, they could triangulate how far the sun was from the Earth and therefore the size of the solar system. In effect, Cook left England to map the goddess of love. Once he had done that, he had a second set of instructions from the Admiralty: to claim land and develop trading links around the world. So this search for the goddess of love went on to British colonialism, taking over land and implementing British ways of being; looking for love but starting to erase ways of loving through the Empire. One of the second installations within the exhibition is the dinner service Wedgwood never made to commemorate Cook’s voyage. There are images recorded by the people who went with Cook to document the voyage, but also images of the goddess of love from Roman mythology, and then of the weapons Cook used to assert control over various places. It’s trying to layer up these complicated and competing ways of understanding Cook as an explorer and discoverer, but also a man who imposed British ownership over land and ways of being that were very alien to those countries.

That was the starting point, and then it was like, how do we move back? I was interested in the journey of Captain Cook 250 years ago, ostensibly to map the transit of Venus in Tahiti. By looking at the movement of the planet from Tahiti, they could triangulate how far the sun was from the Earth and therefore the size of the solar system. In effect, Cook left England to map the goddess of love. Once he had done that, he had a second set of instructions from the Admiralty: to claim land and develop trading links around the world. So this search for the goddess of love went on to British colonialism, taking over land and implementing British ways of being; looking for love but starting to erase ways of loving through the Empire. One of the second installations within the exhibition is the dinner service Wedgwood never made to commemorate Cook’s voyage. There are images recorded by the people who went with Cook to document the voyage, but also images of the goddess of love from Roman mythology, and then of the weapons Cook used to assert control over various places. It’s trying to layer up these complicated and competing ways of understanding Cook as an explorer and discoverer, but also a man who imposed British ownership over land and ways of being that were very alien to those countries.

In your work you confront quite ugly things – is that because they’re the most interesting?

For me, it’s not fun to so much confront ugly things as to provide balance, and I think we’ve been quite bad in this country about providing balance for these collections. Lots of people are doing some great work on allowing non-Western viewpoints a stronger voice within museums, but I think we’ve got a huge way to go to address some of the things the British did as part of the colonial project. It’s not that I want to focus on the bad, but I want to balance out the good with some of the huge downsides that came with that imperial project, so we can have a more grown-up relationship with the world.

Losing Venus is split into four parts, one of which relates to dolls and puppets. Is that linked to the news stories about LGBTQ-inclusive lessons we saw last year?

Not directly, but it’s a really nice connection you’ve made. In the Pitt Rivers there’s a case of dolls and puppets, and the label says dolls are often the way children are taught to become adults and lead adult lives. I was interested in what happens to queer children around the world and what ways of being adults they’re allowed. In some places, like Samoa, there’s a very strong tradition of third genders being part of the community and actively embraced. But how can you have a doll explore the harsh reality of being an LGBTQ adult in countries like Iran and Syria? I wanted to unpick four very different ways, positive or negative, that society deals with LGBTQ adults around the world; how being LGBTQ changes how you can be an adult, and how people have to adapt and modify their behaviour depending on the country in which they happen to be living.

Not directly, but it’s a really nice connection you’ve made. In the Pitt Rivers there’s a case of dolls and puppets, and the label says dolls are often the way children are taught to become adults and lead adult lives. I was interested in what happens to queer children around the world and what ways of being adults they’re allowed. In some places, like Samoa, there’s a very strong tradition of third genders being part of the community and actively embraced. But how can you have a doll explore the harsh reality of being an LGBTQ adult in countries like Iran and Syria? I wanted to unpick four very different ways, positive or negative, that society deals with LGBTQ adults around the world; how being LGBTQ changes how you can be an adult, and how people have to adapt and modify their behaviour depending on the country in which they happen to be living.

What are museums ultimately for, and how do they keep evolving?

There’s no one answer to what museums are for, but the aspect I’m most interested in is that they hold up a mirror and reflect society. In a way, they’re part of the establishment’s system that tells us how we should think and how we should approach ideas, ways of being, and ways people live. Because of that, I’m fascinated by how museums either show progressive, inclusive ways of living, or quite conservative and backward ways. Different museums are on different parts of the spectrum between very inclusive and quite retrograde in their views. I’m interested in how we can help move these organisations to places where everybody sees themselves reflected and everybody feels safe. I think most museums keep evolving. We saw it in 2017, with the 50th anniversary of the partial decriminalisation [of homosexuality]. Museums around the country, some of whom never tackled LGBTQ visibility, suddenly realised that now was the time to start. What’s going to be interesting is how the inclusion of others carries on beyond a one-year programme or when it’s not an anniversary. Organisations like the National Trust are doing some really interesting work on this; how it becomes embedded as an everyday part of the curatorial narrative.