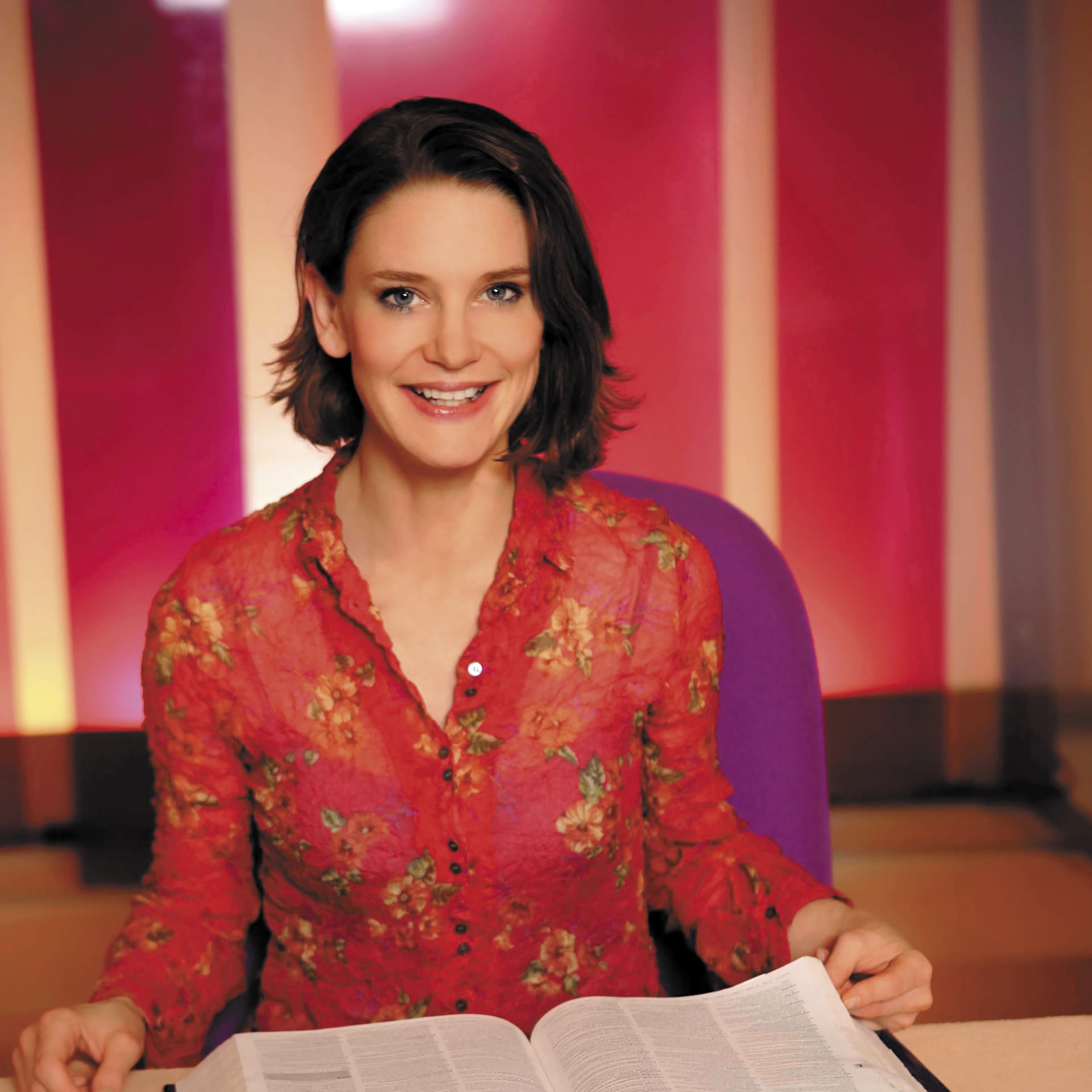

Next month the award-winning Ballet Black returns to Oxford, with the triple bill that is ‘Ingoma’, ‘Pendulum’ and ‘CLICK!’ Fresh from a season that concluded with the dance company joining Stormzy on Glastonbury’s Pyramid Stage, founder Cassa Pancho talks about the mission of the company, and why it’s yet to achieve what it set out to.

Last year Cassa Pancho was awarded the Freedom of London, “a great honour”, she says recalling the ceremony which she attended with her husband. Here she had to declare that she’d inform the Queen if she heard of anything that could lead to the monarch’s harm or injury (“which I like to think I would have done anyway”) and was presented with a certificate. There was a time, she says, where the award allowed recipients to “walk your sheep over London Bridge or something like that, but you’re not allowed to do that now unfortunately.”

It was of course in recognition of Ballet Black’s contribution to diversity in ballet. She founded the company in 2001, four years before retiring from dancing herself, always “more interested in choreography, directing and making the show” than she was appearing in them. “The initial mission was to create a platform for dancers of black and Asian descent, to give them a voice in classical ballet which they didn’t have. I did that by bringing together a company of dancers – including myself – and putting on performances to try and raise the profile of these dancers and create a profile for Ballet Black.”

Back then, why weren’t there opportunities for such dancers? “It’s a lot of things,” says the artistic director. “I wrote a dissertation about the lack of black women in ballet and was told even by some of my own tutors that black people don’t have the body for ballet, can’t do it, aren’t interested in ballet, classical music or classical art in any way, so there would be no point in even writing a dissertation about it – let alone starting a company.” She interviewed black dancers for the assessment, who had been told they wouldn’t succeed in ballet for their bodies didn’t suit it. “That was a prevalent stereotype at the time.”

She set up the organisation as a 21-year-old graduate with no money and “no reputation to back me up”. It was also at a time when people didn’t really form ballet companies; there are some small ones now, she says, “but back then it was the big companies and nothing else. A lot of people said ‘you want to start a ballet company… you’re a nobody in the ballet world. You also want a company full of black and Asian dancers… that’s crazy.’ It took probably ten years for the company to be taken seriously.”

She came up with the name early on, with the intention of using it until she could think of a better one, “something that means Ballet Black but is not Ballet Black”. Nothing else came to her, and the existing handle “outlined what the company was, you knew what you were dealing with when you saw our name, and now 18 years have gone by – if I changed it, people wouldn’t know who we were anymore. I went through a phase of not really liking it, but now I’ve realised that the name itself provokes the discussion and the debate. A lot of people that have never thought about ballet hear ‘Ballet Black’ and it causes them to question why we would even exist.”

Has she achieved what she set out to with the company? “No, not yet. When we’ve seen true progress, dancers will be hailed for their skill first and their colour won’t come up. Instead of saying something like ‘Misty Copeland becomes the first African American principal dancer at American Ballet Theatre’, they’ll say Misty Copeland has been promoted because she’s an amazing dancer. One day there won’t be a need for Ballet Black,” she says, “but I think there really is now.”

In interviews she’ll talk about the above issues, but Ballet Black gigs aren’t about talk. “We show, don’t tell – that’s what I like to think. We’ll just show you it can be done, that all of this is possible, that black artists can be as great at ballet as anyone else. It doesn’t matter what colour you are.”

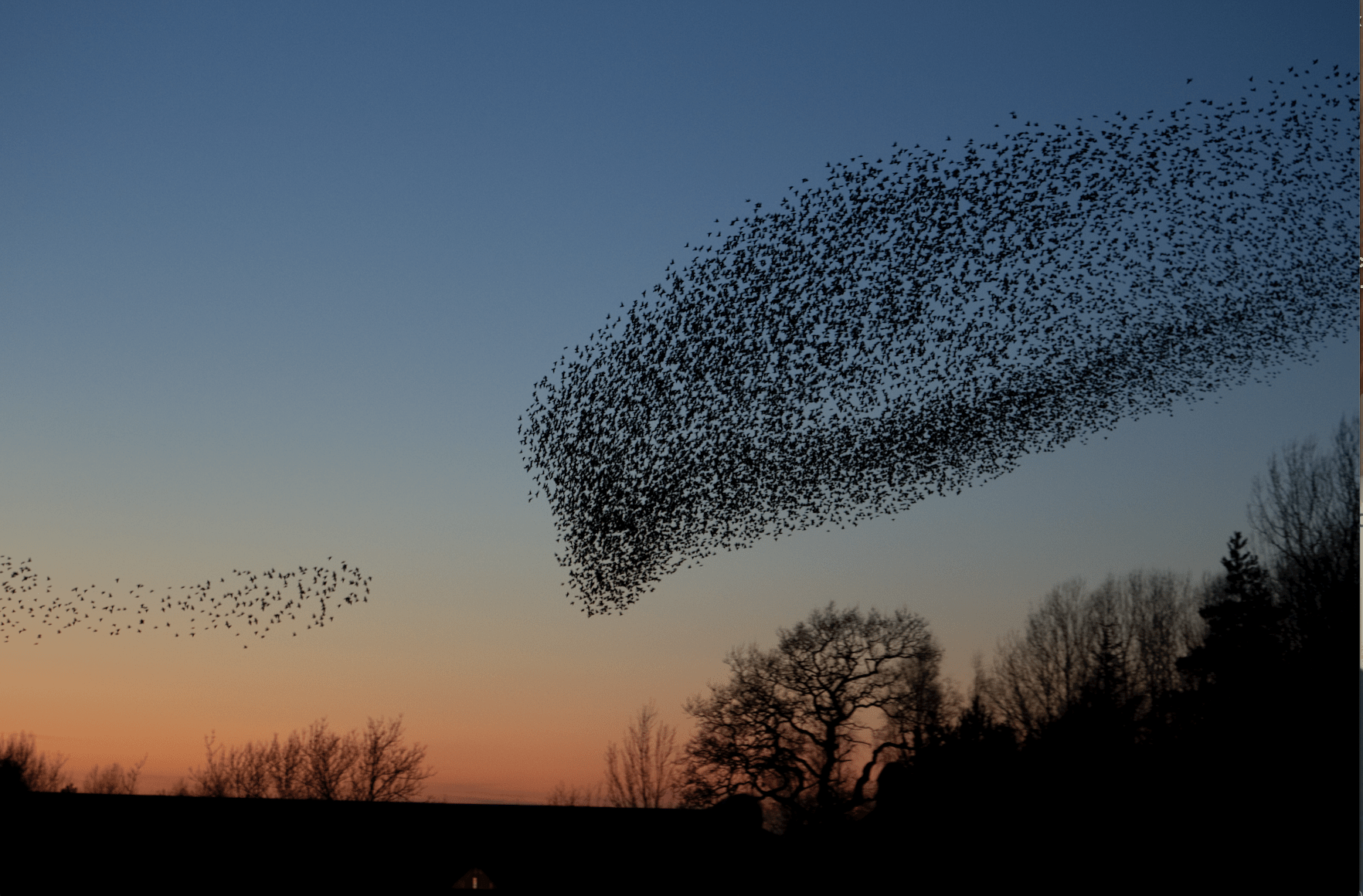

Ballet Black is at Oxford Playhouse 1 November. Its triple bill comprises Mthuthuzeli November’s ‘Ingoma’ (meaning song). A fusion of ballet, African dance and singing, it portrays a milestone moment in South African history and imagines the struggles of black miners and their families in 1946, when 60,000 of them took courageous strike action. ‘Pendulum’ is Martin Lawrance’s intimate duet made for the company in 2009, and ‘CLICK!’ is an original, upbeat piece by Scottish Ballet’s choreographer in residence, Sophie Laplane.