Art and science aren’t always the easiest bedfellows. But for ‘cerebral’ artist Rebecca Ivatts, they merge seamlessly to create astonishingly arresting paintings – many relating to the brain – that are receiving great acclaim from the neuroscience community at Oxford University and beyond.

As with many artists, 47-year-old Rebecca’s muse struck at an early age. “I spent my whole childhood drawing and although I then went on to study languages at Oxford, the irrepressible urge to paint continued. I was a member of Oxford Practical Arts Society at St Catherine’s, I drew at the Ruskin and painted on my years abroad in France and Spain.”

Studying at the Slade, Royal College of Art and Prince’s Drawing Foundation (with a doctor standing by a skeleton and talking students through the anatomy) proved significant as this is where Rebecca learned to draw and paint the nude body, a subject that has dominated her work (one of her early nudes features on Gogglebox). “For me, anatomical knowledge feeds into your imagination as you are thinking about what lies beneath, adding depth, dynamism and interest.”

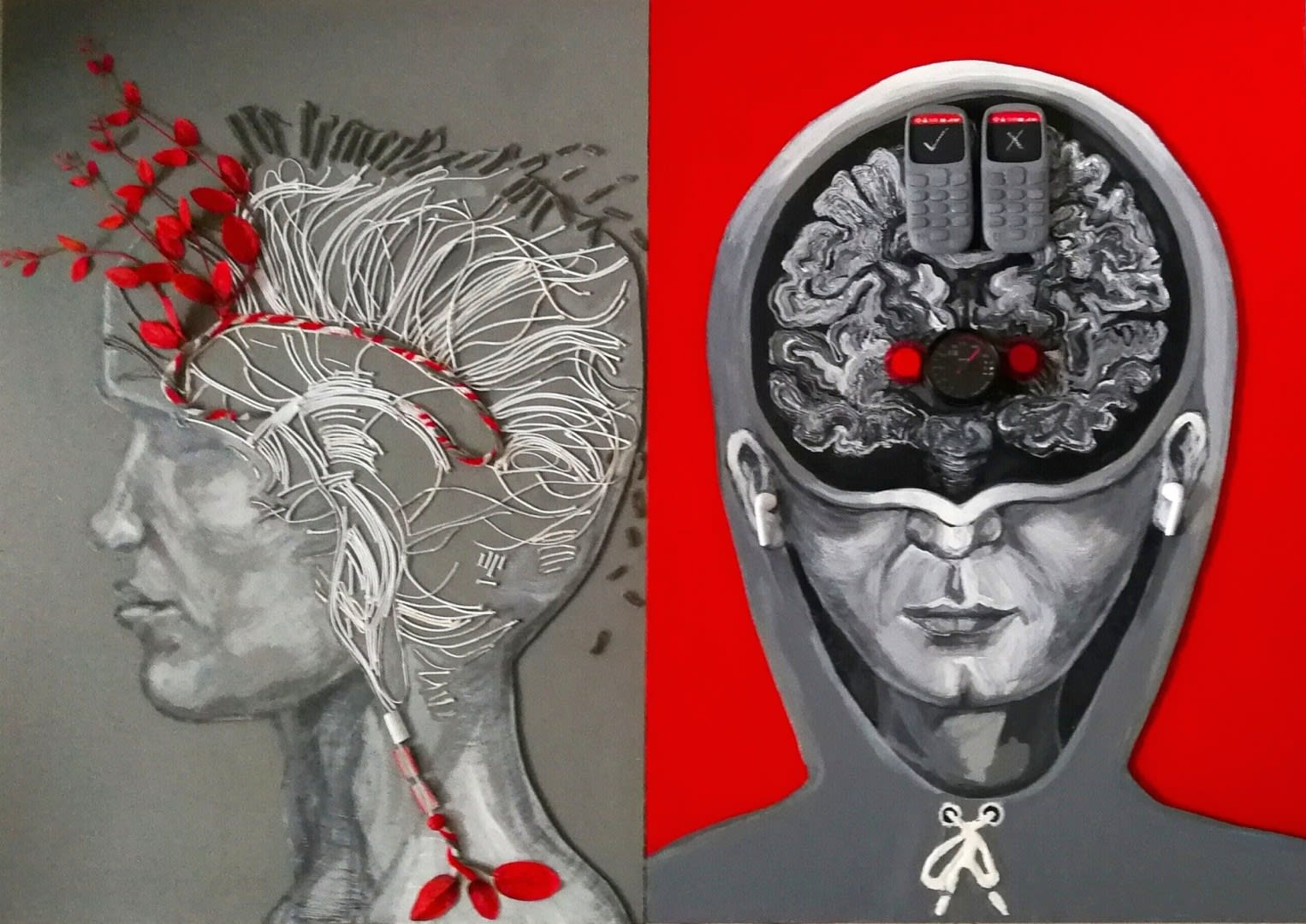

After graduating, Rebecca decided to pursue a career as an artist in Madrid, where the seed for her future brain paintings was sown. “I really love the red, black and white palette so popular in Spanish painting as I can express form in black and white, then add emotional resonance in red. Picasso himself said, ‘No one paints black like the Spanish’. Spanish art is quite visceral – artists such as El Greco and Goya did not shy away from the dark side of what it means to be human.” In Spain, she also saw incredible drawings of neurons by the man considered to be the father of neuroscience, Santiago Ramón y Cajal.

(stroke, creativity)

Rebecca’s fascination with the brain really took off, though, when she had her first child, Johnny, six years ago. “I found the antenatal scans mysterious, fluid and fascinating. Then, by chance, an old radiologist friend talked me through brain scans – an epiphany. In them I could see a whole universe: clouds, constellations, ghosts, butterflies, a Munch-like scream, a dark horse. Medical imaging provided the perfect springboard for both the intellect and the imagination.”

For the past few years, the brain has dominated Rebecca’s work, but what is it about this complex organ that so attracts her? “When one thinks of the real self, what makes one tick, the brain is the personal organ par excellence. What’s more, in my mind, neuroscientists are the new philosophers.”

Her first series, All in the Mind, exhibited at the 2017 British Neuroscience Festival in Birmingham, was “the culmination of three years’ work: a very free, creative, joyful response to brain imaging.” Since then, there has been growing interest from the scientific community. “At that first festival I was approached by an Oxford professor who was very involved in the relatively new field of public engagement, the notion of scientists engaging with the public and communicating what they’re working on via the arts. So, in that context, my work is very timely.”

Although scientific research can seem rarefied, Rebecca’s neuroscience-related work also resonates with young people. “They love my ‘Monkey Brain’ painting. It’s a fun image – a face within a face, cheeky, tongue-in-cheek, the monkey inside us all. Yet a neuroscientist may look at this and think about how the brain is hardwired for facial recognition – it’s a quality of the primate’s social brain. Someone who’s into mediation and mindfulness might think of the ‘monkey brain’ – that place where your wandering thoughts and anxieties take over. In fact, this work is being used for the Pint of Science Festival in May, a huge global student movement, where it will be appearing on T-shirts and beer mats!”

Radley College – very active in the arts with its Sewell Gallery – recently commissioned a teenage brain triptych. For the latter, Rebecca collaborated with the UCL lab of adolescent brain expert Sarah-Jayne Blakemore, daughter of eminent Oxford neuroscientist Sir Colin Blakemore. “They explained why the teenage brain is more sensitive to mental health issues. In this period of change, grey matter volume is decreasing and white matter is increasing, while connections are being pruned back. The emotional centre, or amygdala, is on overdrive yet executive control is immature. It’s this developmental mismatch that makes the adolescent brain so fascinating.”

The scientific/health community has been highly supportive of Rebecca’s research, commissioning and buying works and offering grants. “The stroke series, which I’m working on with the help of Oxford academics at the Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences, has been funded by a grant awarded by a neuroscience journal produced by Oxford University Press.”

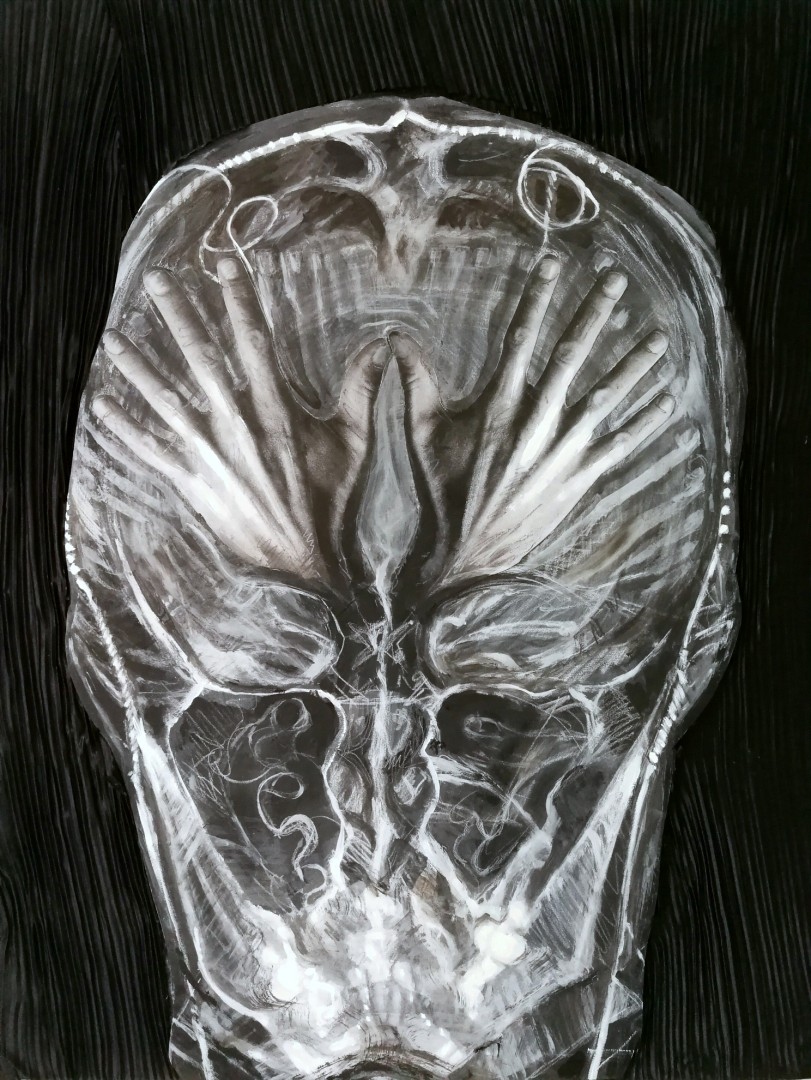

Another successful collaboration has been with Parkinson’s specialist and Oxford professor Chrystalina Antoniades, coincidentally a tutor at Brasenose, Rebecca’s old college. “She showed me a treatment for Parkinson’s called deep brain stimulation – you literally flick a switch and the tremor immediately stops, as if by magic. So ‘Dove of Peace’ is set against silk curtains – a Victorian Gothic image of hands inside a head, like a white dove that might emerge from a magician’s hat.”

“I produced another work for her, about treatment to improve control of eye movements in Parkinson’s patients. When it went on show at the Ashmolean Museum, the chairwoman of the Oxford Parkinson’s Association was visibly moved and said, ‘Wow, this really communicates something of the burden I feel with this’. It was a very humbling moment for me – I stood on the outside of her condition, but I’d managed to express something real.”

As well as an EU-funded symposium ‘Beauty and the Brain’ in Hungary, the past year has included a digital exhibition at the Bodleian Library, a Parkinson’s event and symposium in Oxford, the World Dementia Council summit at the Wellcome Trust and an exhibition in the Ashmolean’s Randolph Gallery accompanied by a talk about neuro-aesthetics, “how our brain perceives artworks and how our eye travels around an artwork”,

Rebecca is delighted that her work resonates equally with scientists and non-scientists and that young people are so impassioned about brain science. “At a UCL/Wellcome Hub dementia event, it was wonderful to see so many dynamic young people involved in this incredible road of discovery to find cures. This global epidemic is no means the preserve of the old.

“I feel privileged to be able to contribute to the understanding of health conditions that affect many people. This is not just art for art’s sake, so maybe has more relevance than über-commercial art, say, a Damien Hirst diamond-encrusted skull.”

She has found researching the brain to be fascinating, joking that she is almost doing a part-time PhD in neuroscience. “For example, the hippocampus – where short-term memories are converted to long-term memories and the epicentre of spatial awareness – is affected by Alzheimer’s. (As an aside, London cab drivers have a very enlarged hippocampus due to studying The Knowledge.)

“My rose brain clock (‘Temps perdu’), a cross between a rose and a brain, shows a stamen-like structure in the centre, representing the hippocampus. A neuroscientist would immediately recognise this – in fact, the chairman of global pharmaceutical company Janssens bought the work. However, it doesn’t take that much explanation to a member of the public either.

“Although I paint a lot around dementia, Alzheimer’s and stroke, All in the Mind also features the creative brain, neuroanatomy, proprioception (our sixth spatial-awareness sense), depression, stress, anxiety and wellbeing, including the effects of meditation and mindfulness.”

To research stroke, Rebecca has gone to the Gordon Museum at King’s College to look at brain samples, as well as attending research and rehab sessions with real patients. “I aim to get across the sense of, ‘I’m still here, don’t forget me.’ In ‘Phoenix’, brain regeneration is depicted using coffee and burnt holes created with a blowtorch, while for neuroplasticity I borrowed the metaphor of gardening. In the brain you want the perfect balance of cells that encourage or inhibit firing – after a stroke you need more firing, but not too much. I want to create positive images too around subjects like the Mediterranean diet, improving brain health, mindfulness, digital detox, social media etc.”

So what’s on the immediate horizon? This month is Action for Brain Injury week and Rebecca will be exhibiting a series of brain works and holding her drawing workshop, Take a Line for a Walk, at the Kennington home of stroke charity Headway – headwayoxford.org.uk

Does she think she’ll ever tire of depicting our mental epicentre? She smiles. “When I started out ‘painting brains’ I had no idea of their power to communicate and educate. Some people say art and science are worlds apart. I totally disagree. Imagination has a huge part to play in scientific enquiry.

“The word ‘brain’ comes with a heavy association and even my husband asks, ‘Aren’t you going to get tired of painting brains?’ But actually I’m not painting brains at all. I’m painting what it is to be us. It’s the prism through which we experience everything.”

Find out more about Rebecca’s work and exhibitions or contact her for commissions at rebeccaivatts.com

and follow her on Instagram @rebeccaivatts