There are around 2,500 breweries in the UK. Given the sheer quantity of beer out there, how do you set yourself apart? While some plumb the depths of Willy Wonka flavours (avocado stout anyone?), others look to flashy branding and catchy names. Stroud Brewery, in contrast, looks to the environment and its community, making beer that doesn’t cost the earth.

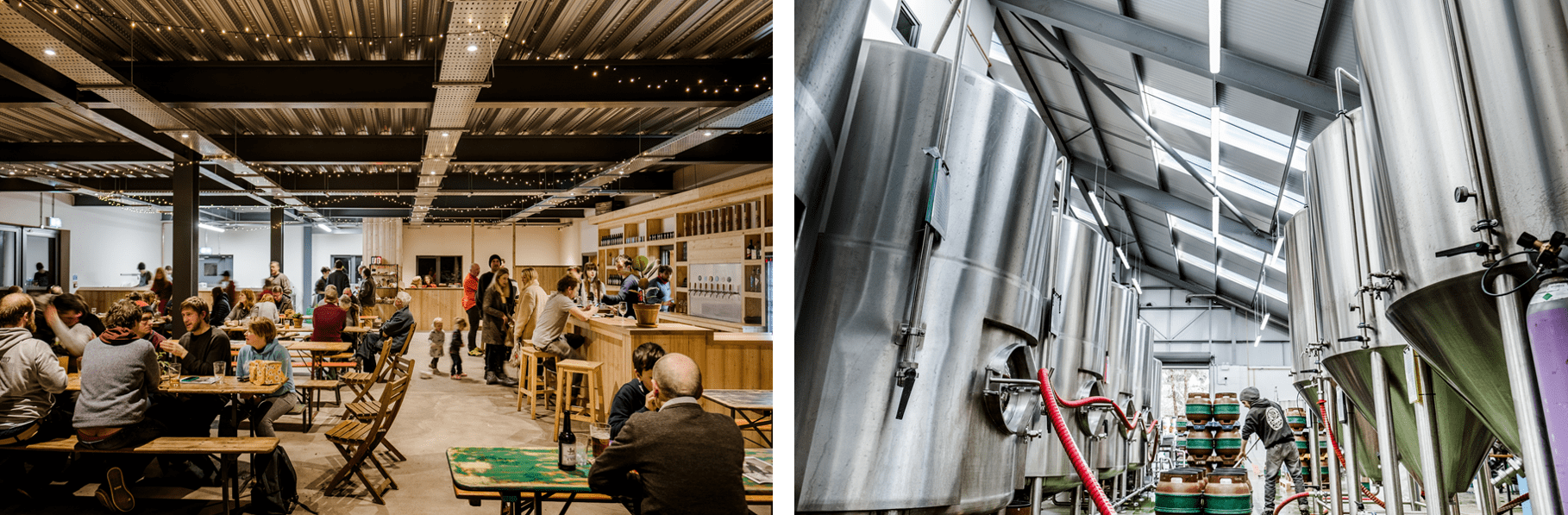

I met founder and managing director Greg Pilley in an industrial estate in Thrupp, in the brewery’s new home, about 75 metres away from where they started. Chatting over tea in the cavernous new building – complete with multiple events spaces, a wood-fired pizza kitchen and long bar it’s hard to imagine the business in a smaller spot. Way back in 2006 Greg began by himself, taking on a brewer in 2008 before he’d paid himself from the business. The bar started life as “blankets on the floor”. Even without heating, people would still journey out to drink, meet and enjoy each other’s company.

A passion for community has underpinned Greg’s circuitous route to making beer. Along the way, he touched on much of what informs the brewery today. After studying marine biology at university, he went back to a farm he’d worked on previously where an inspiration of his “was one of the instigators of the Farming and Wildlife Advisory Group”. From there he did more conservation work in the UK and travelled as a VSO to Nigeria before “getting some sponsorship to look at traditional alcoholic beverages of Africa”. He wanted to disrupt the perception of Africa as “a single country of famine and war and disaster”. Through the prism of drink, he wanted “to illustrate that diversity of life and recognise that the local booze reflected the geography and the climate and that there was a social setting that it was drunk in.”

Publishers were less keen on his idea and his coffee table book didn’t materialise, so off he went to work for the Soil Association in Bristol, writing their technical guide on how to start a vegetable box scheme – “I had my own ambition to set up a veggie box. I wanted to learn about it but there weren’t any resources.” From there he moved to a project focused on community-supported agriculture “exploring different partnerships between consumers and farmers that was more than just buying their product, it was actually having a commitment to the farm in some way”. Through this work, and expecting the arrival of his first child, he came upon Stroud. “I thought Stroud was really cool and had an instant community of people – like-minded, interested in agriculture and all those issues – and while weeding a carrot field with a fellow beer enthusiast, we said ‘wouldn’t it be great if Stroud had a brewery’ and I was possessed thereafter.”

I must agree, Stroud is really cool, and well worth a day trip. There is a calm there so thick you can chew on it. I like it because it’s the kind of place that wears its history with elegance not ego. It doesn’t self-consciously proclaim its accolades – those proud of Stroud take pride in their stride. It’s a radical place with a history of protest dating back to the Stroudwater Riots in 1825. Its citizens have rescued historic buildings, thwarted the vandalism of the countryside, saved hospitals and rebuffed the BNP. It has one of the best farmers’ markets in the country (therefore, the world) and was the home of Britain’s first fully organic café.

The word ‘organic’, like ‘artisan’, ‘craft’, ‘small-batch’, ‘free range’, ‘fair trade’ and ‘hand-picked’, confers a Waitrose-y esteem on things. I think we all know vaguely what it’s supposed to entail, but I wondered if it’s been a little diluted as a concept. “It’s interesting you say that,” says Greg with some eagerness. “The conversation around the question ‘can global breweries brew craft beer?’” It turns out that ‘craft’ has no properly defined parameters, unlike organic, which is “clearly defined in law”. Responding to a survey, 98% of the public believed that big breweries couldn’t, by whatever definition, brew a craft beer. “What they were attributing to ‘craft’ was another value; that they should be independent in order to qualify.”

This is all part of a post-covid shift in consumer preferences. The consumer has become increasingly concerned about provenance and started to divert their reduced spending power away from huge producers towards smaller independents. In terms of our drinking habits, he’s observed that “instead of going to the pub and having a pint of your regular, we’re beer explorers, and life is changing generally for the better from consumption to experience. I suppose it’s a new way of reinforcing your identity – it’s not about having stuff, it’s about having experienced stuff.”

It’s a focus on experience and doing more than just making great beer that has got Stroud Brewery where it is. Of the 2,500 UK breweries, “there are about 25 that are certified to brew an organic product and there’s only five that are dedicated to only doing organic beers – we’re one of them.” That’s a small enough club to be in but not the only one they’ve sought – they’ve also achieved B Corp accreditation, an “assessment of a for-profit business’ social and environmental impact”. This is no walk in the park, covering “sourcing policies, staff welfare, energy use and distance to customers,” – and they’re one of only a pair of UK breweries to have achieved it.

So, what next? Greg, if you hadn’t already surmised, doesn’t believe in growth for growth’s sake. Instead he’s looking to make the new building pay, develop his team and “embed ourselves even more in the local community”. All power to him. For in these fraught and riven times, it’s nice to know some still focus on doing simple things well and with kindness to the earth. This, dear reader, is beer you can feel good about.