The call of the unknown

Throughout recorded history there have been times when the urge to explore previously unknown parts of the world has captured the imagination of whole populations, to the surprise and often consternation of those on the receiving end of these expeditions. Alexander the Great, Henry the Navigator, Christopher Columbus – each led voyages which were to have consequences that resonated through the ages.

In the middle of the 19th century, the river Nile, one of the greatest remaining challenges for explorers, still had its origins behind a barrier of fetid swamps, fatal diseases and seemingly ferocious tribesmen. Its mystery was compounded by reports of fabulous lakes and mountains.

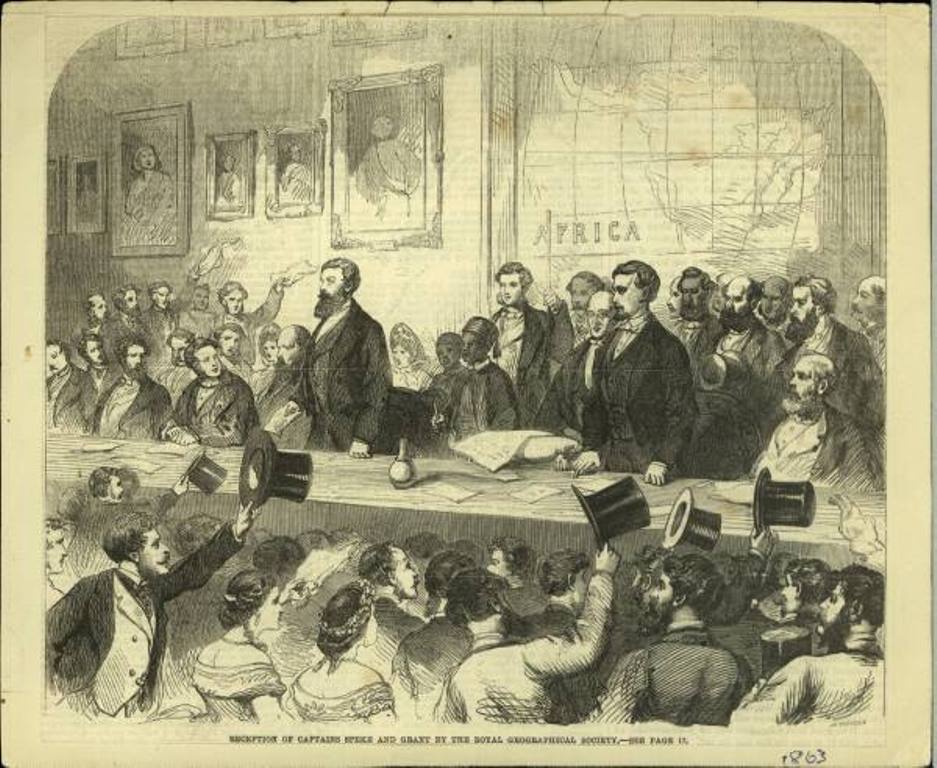

This challenge fired the imagination of The Royal Geographical Society, who had a particular interest in determining the source of the Nile. Thus, in a series of expeditions between 1856 and 1877, several British explorers were sent to unravel the mystery of the source of the Nile. This river, the longest in the world, flowed through the desert, yet brought life in its floodwater every year. Where did all this water come from? The Sudd (Arabic for obstacle) – a huge, papyrus-clogged swamp, thwarted earlier attempts to follow the river upstream.

Until 1856 little was known of the source of the Nile, the great river that was the cradle of western civilisation, that hadn’t been known to the Greek geographer Ptolemy, in AD 150. He had reported that the Nile originated in two great lakes in central Africa about 10 degrees south of the equator, and was flanked by the peaks of the ‘Mountains of the Moon’. This explanation had been incorporated in a map made by an Arab geographer about AD 1100.

In the mid-1850s, the mysteries of the Niger and the Blue Nile solved, scientific curiosity reverted to the next of Africa's great rivers, the White Nile. European missionaries and traders had ascended it as far as the border of Uganda, but beyond here its course was unknown. In 1856, there was a growing feeling within the Royal Geographical Society that the time was at hand to settle the matter.

Lieutenant Richard Francis Burton

Enter Lieutenant Richard Francis Burton of the East India Company's Bombay Light Infantry, a swarthy, moustachioed man of 35 who offered to take an expedition into the region. Burton was already famous for a number of illustrious excursions. He had a remarkable intellect and combined broad-ranging scholarship with eccentric, libertine behaviour.

While in India, he often donned native garb, perfecting his ability to pass as a ‘local’. It was this ability to shed his British persona that enabled him, in 1853, to travel an equally perilous journey to Mecca and Medina disguised as a Muslim Pathan (a native of north-west Pakistan or Afghanistan) and, the following year, to enter the ‘forbidden city’ of Harar (in modern Ethiopia). However, in his later African journeys, he played the role of English gentleman to the hilt.

Speke and Burton - chalk and cheese

The Society accepted his offer, sufficient funds were raised, and the East India Company granted him leave. Burton selected fellow Indian army officer Lieutenant John Hanning Speke as his companion. These two individuals seemed perfectly suited to the task. Burton was already known for his bold exploits and, although he had blighted his prospects in the Indian Service by his bluntness, he was not yet the frighteningly controversial figure he was to become. His linguistic abilities and his evident valour and resourcefulness made him an obvious leader.

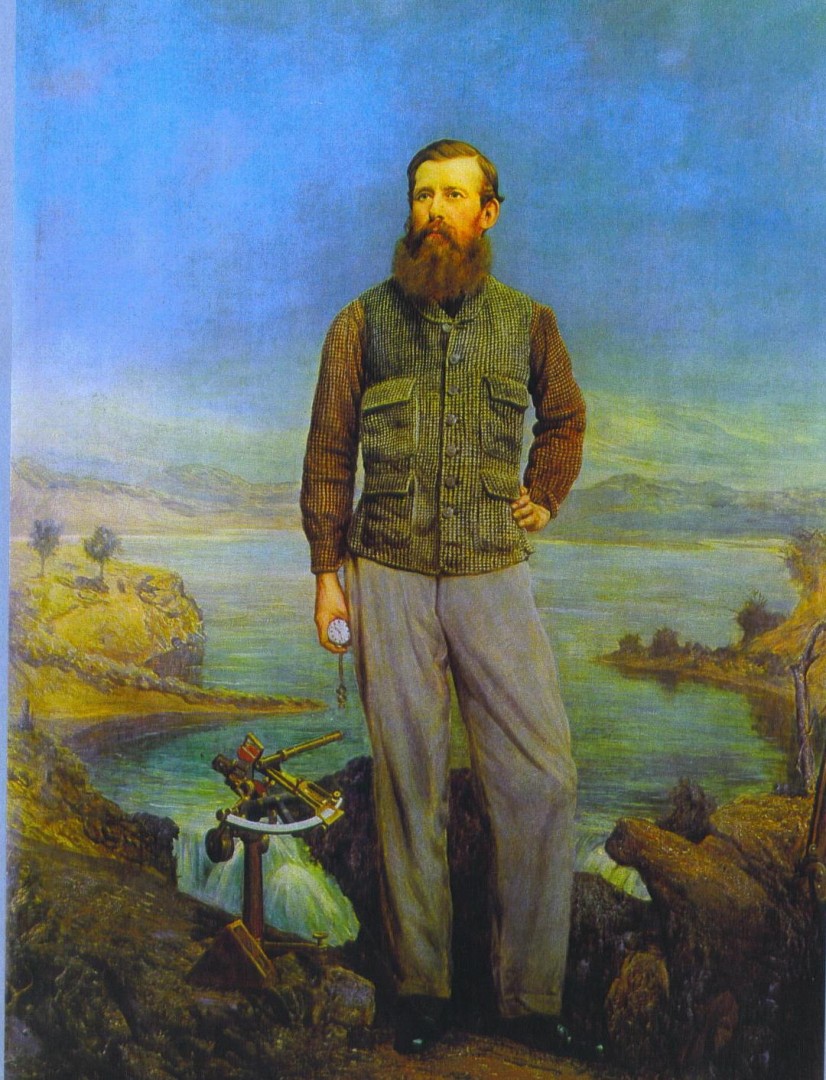

Lieutenant John Hanning Speke

Speke seemed almost as suitable: he’d joined the army of the East India Company in 1844, where he later served under Field Marshal, Sir Colin Campbell during the First Anglo-Sikh War. He was 29 and had considerable experience in collecting botanical and zoological specimens during his leave in the Himalayas and was also an accomplished surveyor. Although appearing complimentary, the two personalities were in fact utterly incompatible and the violent confrontations between Burton and Speke that followed saw armchair geographers taking bitterly opposed sides.

Other explorers were involved in the debate, including David Livingstone, who died whilst trying to clear up the Burton/Speke Nile controversy; Henry Morton Stanley who found his vocation in Africa; James Augustus Grant who joined Speke's second expedition to Africa; and Samuel Baker because he went to verify Speke's theories.

Burton was an enigmatic character, and had developed a taste for wine, women, fighting, gambling, mysticism, daredevilry and languages. They were the precious tools with which to satisfy his insatiable curiosity about exotic peoples. In India, Burton's rapid mastering of Persian, Afghan, Hindi, Urdu, and Arabic won him the friendship of Sir Charles Napier, the British general and Commander-in-Chief, famous for conquering the Sindh (in present day Pakistan), to whom he rendered superlative service as an intelligence officer. He earned the animosity of his superiors in the East India Company when he told them that they were losing touch with their subjects and made an accurate prediction of the approximate date of The Indian Rebellion of 1857, which began as a mutiny of sepoys of the East India Company's army on 10 May 1857, in the town of Meerut.

In 1854 an earlier expedition led by Burton to penetrate central Africa from the Somali coast led to disaster. He was accompanied by Speke and two fellow officers, Lieutenant G.E. Herne and Lieutenant William Stroyan and a number of Africans employed as porters. Shortly after they met on the coast, their party was attacked by a group of Somali warriors. In the ensuing fight, Stroyan was killed and Burton and Speke were both severely wounded. Speke was captured and stabbed several times with spears before he was able to free himself and escape. Burton was impaled with a javelin, the point entering one cheek and exiting the other. This wound left him with a notable scar that can be easily seen on portraits and photographs. He was forced to make his escape with the weapon still transfixed through his head. The expedition was only saved from destruction because a friendly Arab boatman took the survivors back to Aden. Although Burton, in his report to the Royal Geographical Society criticised Speke, he nonetheless annexed Speke's notes on the botany and zoology of the area to his report. Speke felt humiliated and ill-used; their relationship was already an explosive, psychic mixture.

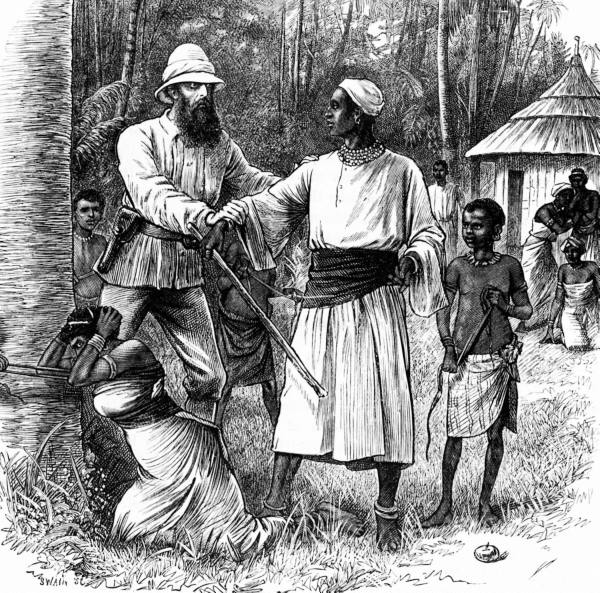

An early illustration depicting John Hanning Speke restraining the hand of Mutesa I, the reigning Kabaka (King) of Buganda, who was about to strike a tribeswoman accused of theft.

Speke, as fair and charming as Burton was saturnine and sarcastic, was born of a Devon family whose origins went back to the Norman Conquest of 1066. He was a fanatic about personal fitness, dominated by his mother and sisters, awkward in the company of women and had a narcissistic tinge to his make-up. He joined the Army of the East India Company at the age of 17, and his duties took him to the Punjab.

In India Speke had the good fortune to meet James Grant, the Scot who was to play an important role in the future. Grant had been commissioned in the East India Company's Army in 1846, and served during the Anglo-Sikh Wars and Rebellion of 1857. Grant was loyal, obedient, and fully capable of carrying out his duties independently if necessary, but also willing to follow an order to the letter. In this friendship however, Speke was the impetuous leader, while Grant was the cautious, admiring follower.

Despite his blundering during the earlier expedition, Speke was invited by Burton to join his official ‘Great Lakes’ expedition to central Africa in 1856. Burton later said that he took Speke to ‘give him another chance’. Speke was however determined to be associated with the Nile discoveries.

Some of the African porters who accompanied Burton and Speke on their historic expedition to find the source of the Nile, are pictured here in an engraving which appeared in the Illustrated London News following their return to England in 1858.

In 1857, the two partners embarked at Bombay and landed at Zanzibar. They made hasty preparations for the march inland from Bagamoyo (in modern Tanzania). With help from the British Consul, Colonel Atkins Hamerton, Burton and Speke assembled their party which included 36 African porters, 10 gun-carrying slaves, four drivers and a posse of Baluchi soldiers to protect them. There was much additional equipment required including ammunition, medicines, stores and an iron boat in seven sections intended to enable them to explore the great lake. As a consequence a second caravan was organised to carry the additional suuplies. On 25 June 1857, the march began.

A forgone conclusion?

In the early stages of the expedition Burton overheard the Hindus telling each other that he would never get as far as Ugogo (not a third of the distance) whereupon they would seize all his belongings; he then had his moment of despair. The caravan proved to be only nominally under the command of its European leaders. The column moved at its own pace; indiscipline was the rule, theft endemic, and desertions began as soon as the men marched from the coast.

Within three weeks they had covered 118 miles with more than 600 ahead of them, both men were already so sick they often had to be carried. Smallpox was rife and the way was well marked by the bones of slaves who had died of this and other diseases. When they finally reached Morogoro they were, said Burton "physically and morally incapacitated". At this point the Baluchi soldiers mutinied and had to be quelled by an emaciated Burton who faced them down with a revolver in his hand.

Throughout the journey, and despite his ill-health, Burton continued his ethnological studies, which were so uncomplimentary to the natives that they are unprintable today. By the time they reached Ugogo, half the supplies intended to last a year had been consumed or stolen. This was very serious because the local tax, called ‘hongo’ payable to chieftains over whose land they passed was rising progressively and had to be paid out of the supplies they carried.

The travellers’ health improved as they reached the savannah country. Tattered and emaciated, the two Englishmen walked into Kazeh on 7 November 1857, Speke was almost blind with opthalmia. There they learned that there was not one but three great lakes or seas: The Sea of Niassa to the south; The Sea of Ujiji (Lake Tanganyika) just ahead, and The Sea of Ukewere (Lake Victoria) to the north. On the morning of 14th December they were in sight of Lake Tanganyika and despite their incapacity and disabilities they attempted to explore the lake in a canoe, much too small a craft for such a large body of water.

The most urgent task was to find what outlets there were from the lake, and thus to decide whether the Nile had its origins here. But they were unable to reach the northern end of the lake. However, the natives assured them that at the northern end there was a river, The Ruzizi, which flowed into and not out of the lake, meaning it could not be the source of the Nile.

Credit where credit is(n't) due

Their position now seemed so desperate that Burton decided to return to Zanzibar with news of the discoveries thus far made. Speke later claimed that he suggested that they should march north from Ujiji, to The Sea of Ukewere but Burton felt unable to do so, even though the relief caravan had arrived. It had been badly plundered en-route and the goods it brought quite insufficient to enable the party to barter its way onwards. Had a further journey been possible, Burton would have discovered that Lake Tanganyika was 400 miles long. As Burton continued with his ethnological investigations Speke was furious by the time being wasted, so he persuaded Burton to permit him to take a small party on a three week trek to the reputed ‘Sea’ to the north.

Speke made a momentous foray northwards, and three weeks later, on 3 August 1858, beheld the huge expanse of The Sea of Ukewere, which he decided in a flash of inspiration was at last the Ptolemaic source of the Nile. He then hurried back to Burton to announce the great discoveries. Burton at first received the information coldly, then whilst acknowledging that Speke had found ‘a’ lake, demanded what possible proof he had that it was in fact ‘the’ lake.

An argument for the ages

And so began an historic quarrel, Speke arguing – without foundation, but accurately – that Lake Victoria was the birthplace of the Nile, and Burton countering that it was Lake Tanganyika. After convalescing, Burton returned to England to find that Speke had already presented his version to Sir Roderick Murchison, the President of Royal Geographical Society.

To Burton's chagrin, the RGS favoured Speke's conclusions, and in 1860 Speke was sent back with James Grant for further exploration. Over the next three years, the two made many discoveries, including the Ripon Falls, where the Nile flows from Lake Victoria. However, they failed to prove Speke's theory because they did not trace the continuous course of the river. The conflicting claims of Burton and Speke resulted in a debate being scheduled at the RGS for 16 September 1864. On the day before the meeting, however, Speke died under mysterious circumstances while shooting partridge on the Neston Park Estate, Corsham in Wiltshire. Although probably accidental, the Burton camp would forever claim suicide.