Artist and computer programmer David Woollard uses computer technology to create detailed and imaginative drawings ranging from detailed geometric mandalas and pictures of chaos theory to typographical slogans and golden will-o-the-wisp fractals that seem to hang three-dimensional in space.

He tells Esther Lafferty, “I learnt to code when I was tiny and I was always interested in the quirky side of programming and in using maths to create interesting shapes. I used to create different kinds of digital art in a web browser and then lockdown happened, which is when I started experimenting with machines. I found a machine that was available in China, the Eleksmaker, which could translate my on-screen creations into work on paper. It wasn’t a great machine – and I use an Axidraw robot now – but as I began using it, I discovered a large on-line community that was into making art with machines.”

David’s dad, who is a retired electronics engineer working on big infrastructure projects, was an inspiration to him, connecting him to numbers and patterns when he was a child as he helped him with his maths homework, and David’s mum is a crafter who enjoys scrapbooking and other art forms. Both, he says, have always been totally supportive of all his ventures, and David is proud, therefore, to be weaving their disparate influences together within his hyperkinetic art.

“It started off as nothing more than a bit of fun, but some of the drawings I – or we, because I call my Robot ‘Stephen’ – were making were really beautiful and I was getting great feedback on Instagram (@hyperkinetic.art) and I’m thrilled that what began as a hobby has grown into something much more.”

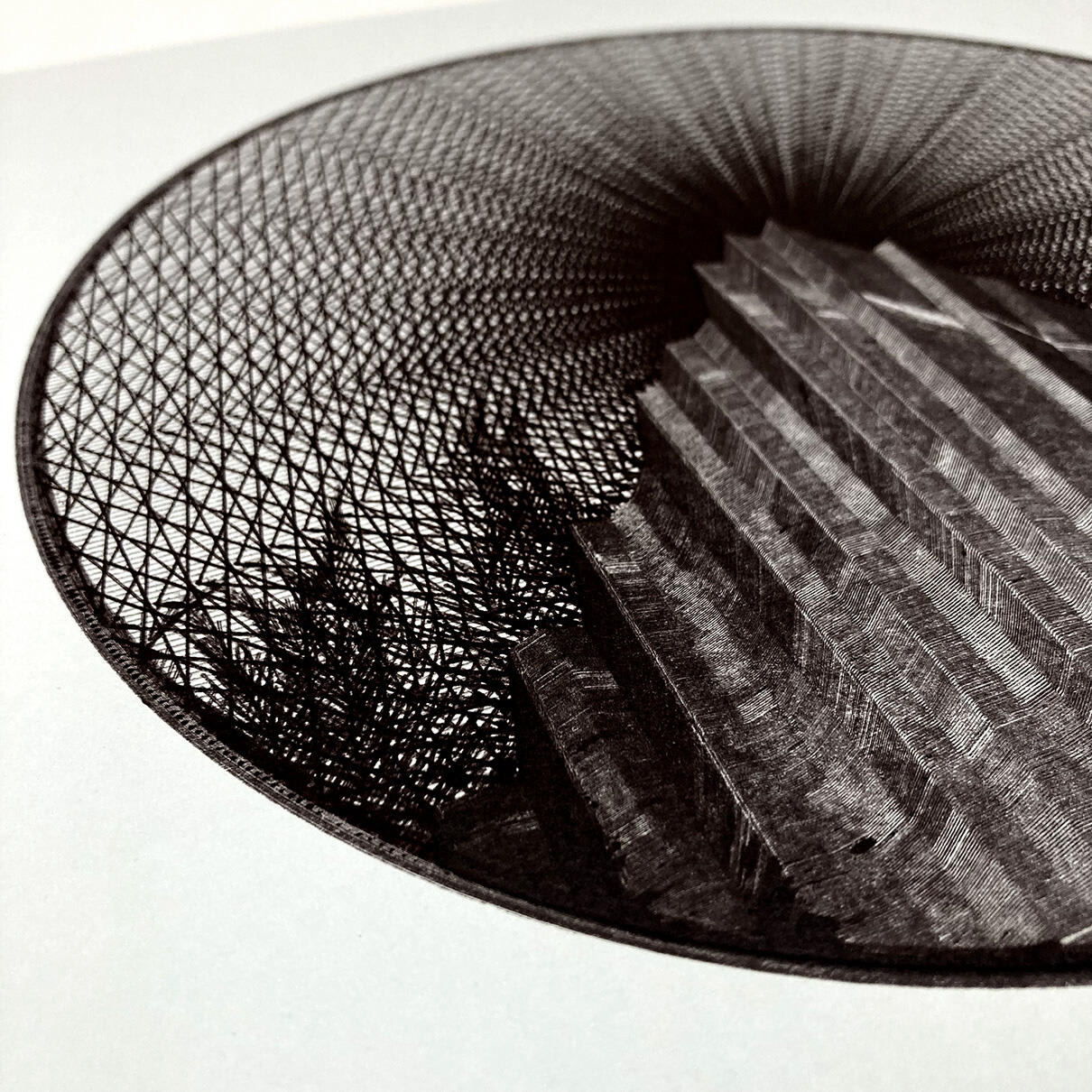

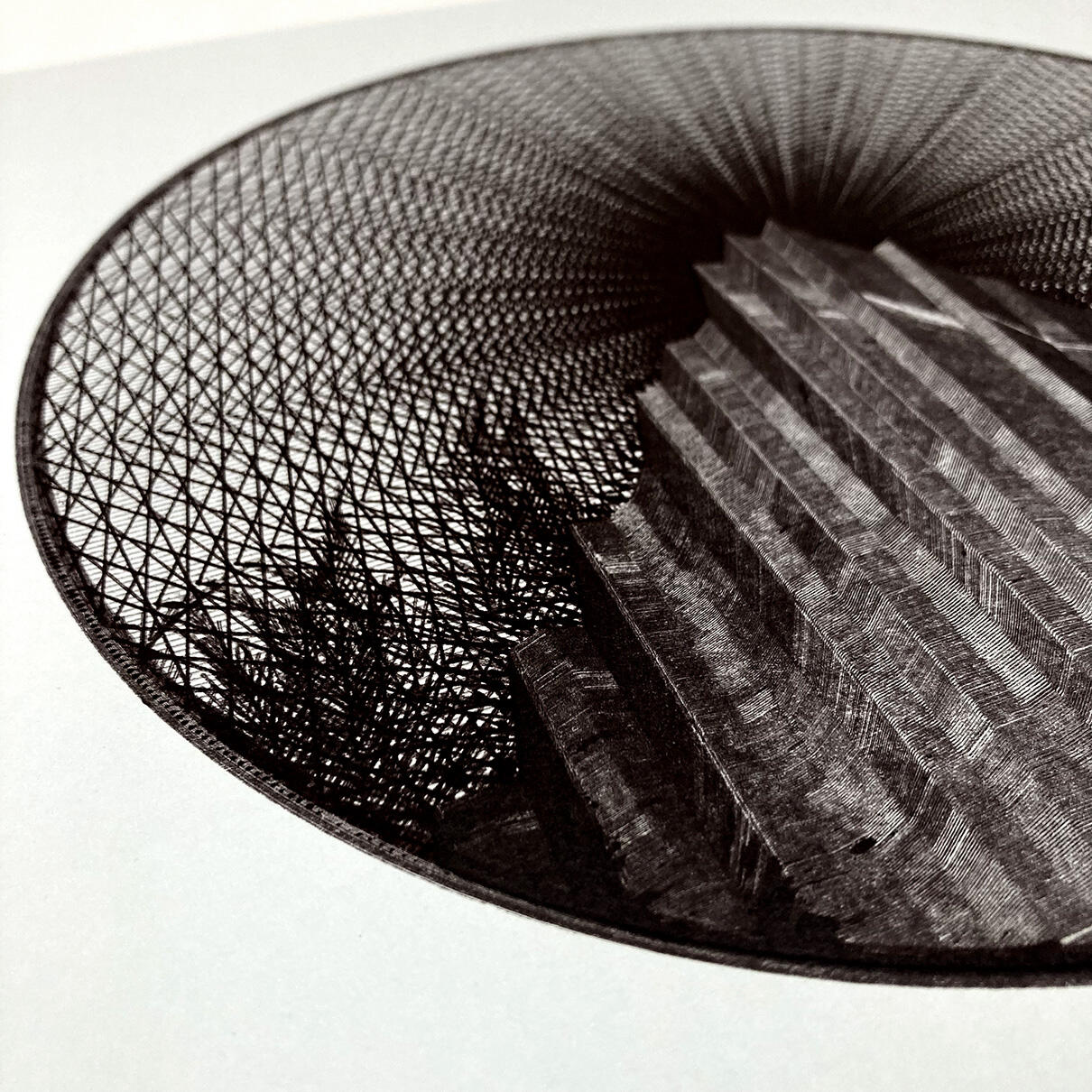

“To start a new piece, or series of work, I simply pull a problem to solve from my neurodivergent brain, like generating art in a particular form, or a mathematical thought to represent, and then I devise the relevant instructions. The speed and acceleration of the pen varies the thickness of the line, and the robot works slightly differently on different papers and textures: a piece can take anywhere from half an hour to several hours to generate, and I bear these things in mind as I approach each piece.”

David goes on to say, “Whatever people generally think, computers are actually pretty stupid, and humans aren’t. Computers are completely reliant on the input from a user, a human. The computer’s strength though is precision and persistence. It can draw 100,000 lines, all slightly different and it doesn’t get bored so I’m using a robot as a tool – it isn’t the creator. People often ask me about AI, but this is entirely different in that the final piece is very much a man-made design.”

(As an aside, David is actually anti AI-art because while AI doesn’t produce a direct copy of anything, it is drawing on work by hundreds of artists around the world who have used their skills and imagination to produce works of art, assimilating them all and spitting out a randomised version derived from the sum of their efforts. AI can’t generate art in a vacuum – it is using the work of all those who have gone before. In contrast, although David’s art is generative, drawn with computer codes, it’s the result of hours of his individual thinking and planning.)

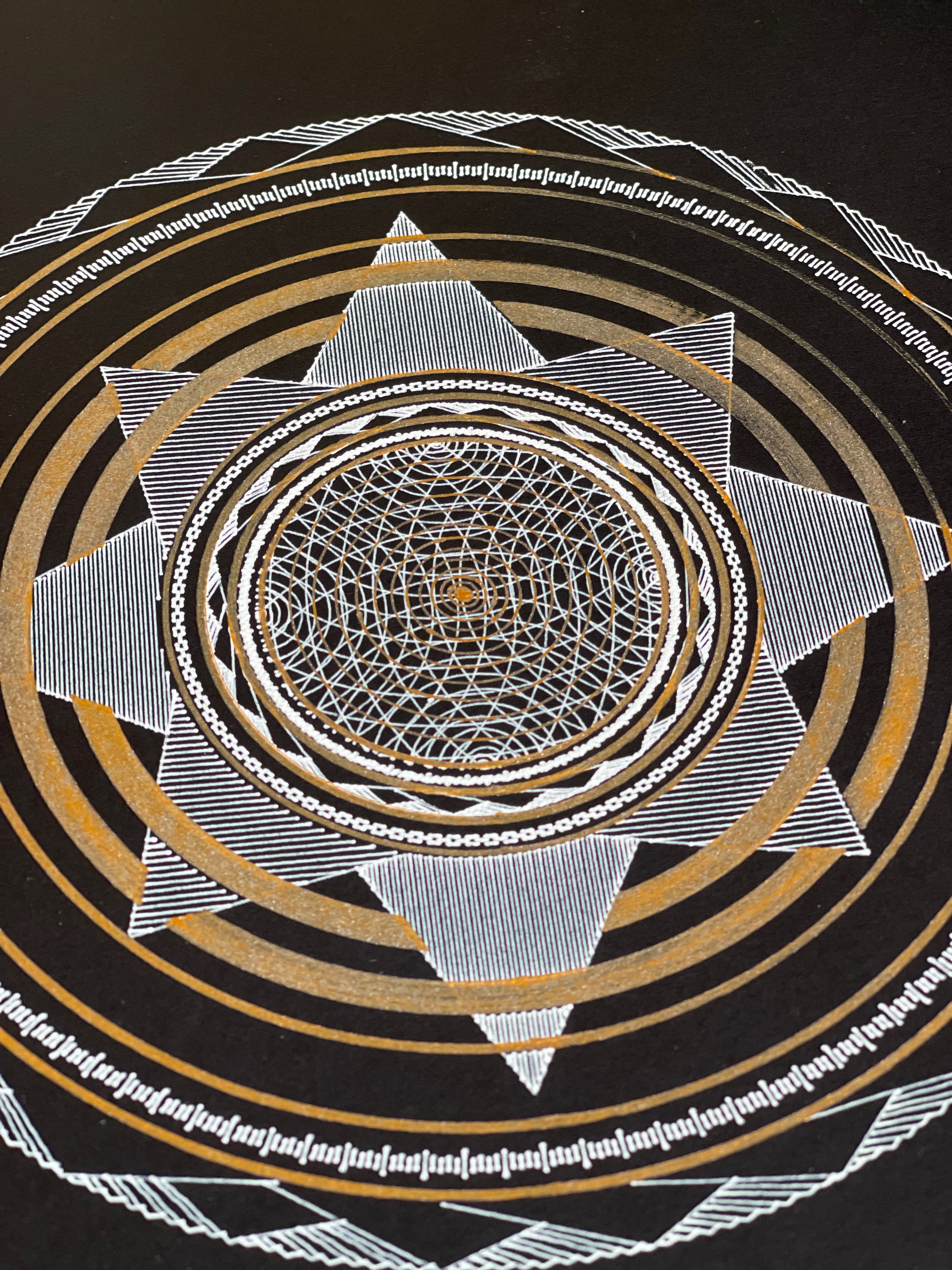

“My current obsession is compasses – the ornate illustrations on old manuscripts are so beautiful, and yet a compass is essentially a set of overlapping shapes that intersect around a central point, and this inspired me to create contemporary versions. The process is rather like reverse engineering – I am starting with an end point in my mind and building code that will generate a line drawing. I probably discard more than 99% of the outputs but it is wonderful when there’s a happy accident and it looks beautiful.”

David’s series include Mountainscapes, based on a Gaussian distribution (a widely-used statistical function), which have different peaks and troughs every time he runs the code; feathers in different shapes and sizes, which are based on Pi “because feathers are essentially a series of curved lines that come from a central curve”; and trees. “I generate trees from fractal shapes,” he explains. “If you start with a line that splits in two, and that’s repeated over and over again, you’ll have many branches. Some of the versions the code generates are as beautiful as real trees. I’m thinking about moving into 3-D next,” he continues, “coding 3D-printed self-supporting Bonsai trees.”

There are further series developed from sine waves in which David’s lines progress from linear to wavy and chaotic; Boolean geometry in which, polygons are ‘smashed up’ and reconstituted in a stained-glass effect; and gravity in which David simulates laws of motion. This later series has an unexpected wispy, ethereal quality, as organic shapes twist and turn like starling murmurations.

David also has some typographical designs, text-based slogans generated geometrically – these are emotive phrases or lyrics that from bands that have moved him. Some have apolitical undertone: “Give it all back to the animals,” for example, refers to the way we approach the planet and his thoughts about the future.

An insight into AI Art, Tony Wyer

“Last spring I listened to a piece on BBC Radio 4 about the new apps that are available to create AI-generated art, and had a go at using them,” says Tony Wyer. “I was very impressed with what I created, a painting rendered in an impressionist style of Longbridges bathing station close to Donnington Bridge, based on a photo I had taken. Shortly afterwards, just after a winner at the Sony World Photography Award 2023 was announced, the artist revealed that his work, Pseudomnesia: The Electrician, had been created using AI. Also last year, a sculpture The Impossible was created entirely by AI in Sweden, taking the essence of well-known pieces by classical masters including Michelangelo and Rodin.

It was then that I became really interested in the use of AI in art, right from its early development by the ‘Godfather’ of AI art, Harold Cohen (a British-born artist who developed a computer programme, AARON, to produce drawings and paintings autonomously, through to Ai-Da). Oxford has been at the heart of the AI and art debate, ever since the humanoid artist-robot, Ai-Da, and her art was first presented to the public here in 2019.

Over the past year there has been a real increase in the sophistication of tools that anyone can use to generate digital pictures and the images it can create are amazing. There’s a large sharing community on-line using the technology, that seemed skewed to creating fantasy images of castles, dragons, and pets too, but I wanted to do something more aligned to mainstream fine art.

Although AI Art is a small movement, a stand-along genre which won’t replace traditional creativity and art, we can’t simply dismiss it: it is coming and so we should embrace discussion around the field. After all, there were plenty of people in the mid-nineteenth century who thought that the advent of photography would be the death of painting, and that hasn’t proved to be the case: now plenty of painters use photography as an aide-memoir or an alternative to sketching scenes en plein air.

AI technology is reliant on creative input and I envisage most artists feeding ideas into AI as a textual description – ‘the art of the prompt’ – and seeing what is generated to develop and refine their ideas and imagery rather than producing finished works.

I create my series of AI-generated images, labelling them to include the prompts and ‘refiners’ used to create each piece, and the pictures range from a flooded landscape to post-industrial abstracts and a pair of portraits of Dante and Patrice first influenced by seventeenth-century art, and then envisaged in the 23rd century. Just as early science fiction from Oxford influenced inventions and thinking in the first half of the twentieth century, might AI art influence the future? Who knows where it will take us?