Have you ever flirted with your satnav? Do you find its voice reassuring as you negotiate traffic? Do you joke with Alexa, and thank her as she gives you the weather report and places your online shopping order? Where will these applications of artificial intelligence take us in the future?

With a rather 1970s hipster aesthetic and a sci-fi slant, the 2013 film Her, written and directed by Spike Jonze, is a futuristic romance and a thought-provoking exploration of intimacy in the 21st century; exploring how we might connect with one another maybe 20 or 30 years from now. The main character Theodore Twombly (Joachim Phoenix) is a lonely oddball who sports a distinctive moustache and heavy tortoiseshell glasses. Despite writing lyrical love letters for other people professionally, he can’t find the right words to maintain a relationship of his own.

Step up ‘Samantha’, a state-of-the-art tailor-made operating system with the velvet voice of Scarlett Johansson, who reads him like a book and instantly manages his life with silky ease. She’s caring, funny and always there for him: of course, he’s going to fall in love. The pair seem like the perfect partnership – or as close as you’re going to get when one of the pair has no physical manifestation –but it isn’t only Theodore whose life has changed. What will happen as Samantha, ‘born in Theodore’s computer’, becomes increasingly self-aware and develops a desire to be human and have her own body? As she continues to evolve emotionally and applies the seemingly infinite capacities of artificial intelligence to her own existence, where will it lead?

Her raises issues ripe for discussion. From the insidious impact of Siri, Alexa, Cortana and Google Assistant as their almost-simpering female voices sweetly and politely reaffirm misogynistic social norms, to whether it is dangerous to hand over your self-determination to any form of AI, and the role of technology in relationships.

During an IF Oxford event, Her: artificial intelligence and human nature at the Ultimate Picture Palace on Thursday 13 October, visitors will have the opportunity to watch the film then join a panel discussion with researchers from the University of Oxford Nuffield Department of Clinical Neurosciences. Discussants will include Saad Jbabdi, Professor of Biomedical Engineering and Ben Seymour, Professor of Clinical Neuroscience whose work focuses on pain and aversive learning using virtual reality.

Together, visitors can explore questions of consciousness, the very human feelings of loneliness and anxiety, and how these manifest in the brain. It’s intriguing to consider the brain’s response to objects that we know are not alive, and the evolutionary pressures that have perhaps prompted us to find humanity in robots. Why do we attribute agency to them, even though we know it is only through human programming that they behave the way they do? As the fields of artificial intelligence and machine learning grow with new mathematical thinking and practical applications, you might also ask where this could take us?

How different is Theo and Samantha’s connection from a long-distance relationship? Could an operating system ever reciprocate genuine feelings and how would the couple have a sexual element? Could AI ever really replace human love, and at its root, what even is love? Would culture be willing to accept such a human-digital romance? Would you? And might we one day consider a polyamorous robot or an operating system to be a form of sentient being; what impact might this have on society’s moral codes?

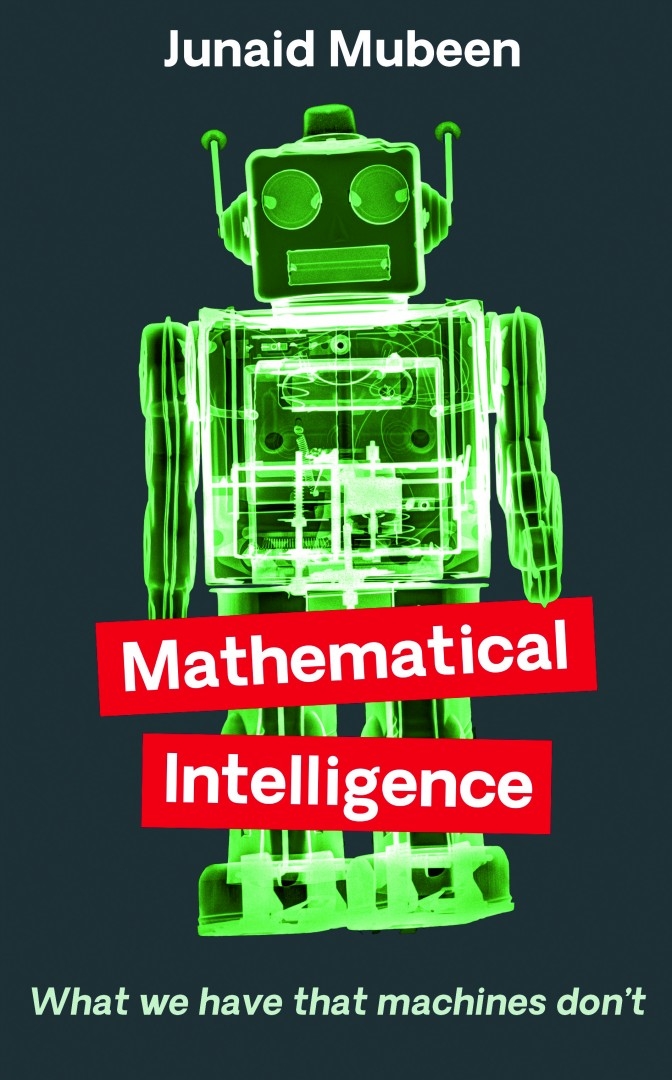

Book Review: Junaid Mubeen: Mathematical Intelligence – What We Have That Machines Don’t

There is no doubt that AI is extremely powerful and is changing the way the world works – but will computers ever overtake humans and relegate us to second place? Or, do humans actually have the edge? In a new book, Mathematical Intelligence, What We Have That Machines Don’t (Profile 2022), mathematician-turned-educator Junaid Mubeen argues that we have a remarkable system of thought developed over millennia. While we can’t match the arithmetic and pattern-seeking abilities of a computer, we have alternative mathematical superpowers. Computers can process vast calculations at mind-boggling speed, but the scope of their abilities is limited by the models we feed them: although computers work with an enviable precision, the human ability to simply estimate is remarkable, Junaid argues.

There is no doubt that AI is extremely powerful and is changing the way the world works – but will computers ever overtake humans and relegate us to second place? Or, do humans actually have the edge? In a new book, Mathematical Intelligence, What We Have That Machines Don’t (Profile 2022), mathematician-turned-educator Junaid Mubeen argues that we have a remarkable system of thought developed over millennia. While we can’t match the arithmetic and pattern-seeking abilities of a computer, we have alternative mathematical superpowers. Computers can process vast calculations at mind-boggling speed, but the scope of their abilities is limited by the models we feed them: although computers work with an enviable precision, the human ability to simply estimate is remarkable, Junaid argues.

A classic Fermi, or estimation problem, is "How many piano tuners are there in Chicago?" a question that is almost impossible to answer correctly. You need make a series of assumptions in order to hazard a guess. You might begin by guessing the number of pianos you could expect to find in a big American city and divide by how many instruments a piano tuner can tune in a year, you will have an estimate of the number of tuners. It’s a rough and ready approach but is a lot quicker than knocking on every door with a clipboard. A computer can do neither!

In essence, a computer simplifies all objects to strings of numbers, so, asks Junaid, how can it ever understand the pure ‘dogness’ of a dog? A small child builds a reliable mental picture through exposure to canines of every shape and size and even the best self-learning computer that has ‘seen’ thousands of dog images can recognise a dog-shaped object reliably, but will never understand that it is a living being or how it might make us feel. Artificial intelligence has no imagination; it cannot define goals, question a purpose, or share intentions with others.

In this day and age, where we fear the threat of artificial intelligence, this fascinating overview identifies seven areas where human intelligence can’t be matched, and in so doing, Junaid puts paid to the idea that we will soon succumb to robot overloads. He gives us hope that our innate mathematical talent, honed with good teaching and mathematical self-awareness, will harness the power of AI and give us maximum freedom to flourish. Go forth and multiply.

Mathematical intelligence: Waterstones Bookshop, OX1 3AF

Thursday 20 October, 6.30pm