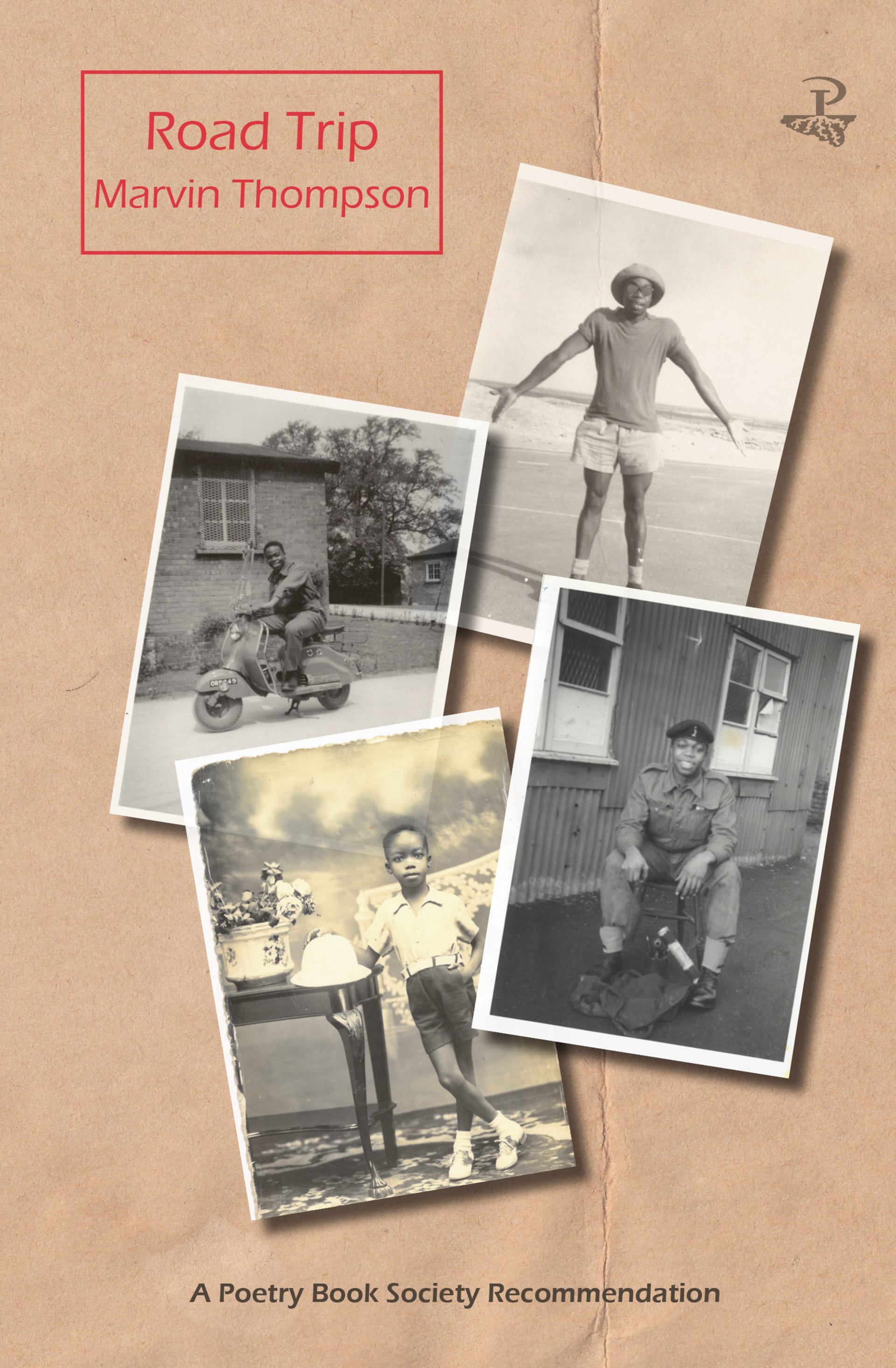

Following its release in March, we spoke to teacher and poet, Marvin Thompson about his first poetry collection, Road Trip, an intense interrogation of culture and heritage. From Wales, he discusses the incentive behind the book, and the importance of poetry for young people today. We also explore with him the complexities of the Black Lives Matter movement and navigating prejudice as a person of colour.

How have the past few months been for you as a teacher?

As much as it was stressful and as much as you’ve got the children’s wellbeing to think of, I didn’t have the added stress of worrying about my job. But in early May, there was a report that BAME people were more likely to die from COVID-19 – for multiple reasons which weren’t explained. Then in early June, it was, ‘Right, back into school.’ I didn’t get my risk assessment for vulnerable people in schools for another month. It was like, ‘You’re more vulnerable but we’re not going to tell you why.’ At the time of the Black Lives Matter demonstrations, the government came out saying, ‘We’re not going to release the report on BAME and COVID-19, because we think that might inflame the situation even further.’ That was quite a stressful time for me as a black father. What must this country think about people like me, to say, ‘Because you’ve been protesting, which you’re legally allowed to do, we’re not going to give you the information which we medically should.’? Ultimately my school was really good with me and I felt assured that a system was put in place. Don’t get me wrong, it’s very difficult. You’ve got to marry-up the education of the kids and the economics of the country, but it would just be nice if there was an official acknowledgement that it’s tricky for a lot of people and it doesn’t feel like that has been the narrative.

Do you speak to your own children about black history?

When I first started writing Road Trip, I wrote it as a book for me, but then when I started writing more about my children, I realised this was a book that in later years, my kids could perhaps read and learn from. From then on it became a project of writing the book for them. In terms of teaching them, I’ve always immersed them in their black and Jamaican culture because my parents are from Jamaica. I’m very aware that they’re going to get a good schooling in their Welsh and white British culture – and that’s brilliant – but I see it as my job as a parent to also give them a good schooling in their black and Jamaican culture. We will listen to lots of jazz, reggae and soul-music, we read biographies of Serena Williams and the scientist Maggie Aderin-Pocock. We watched this great film called Hidden Figures which is about African American women who are engineers and mathematicians on the NASA space programming in the 60s. I’m not trying to indoctrinate my kids, I’m just trying to give them a range of experiences so when they’re older, they can feel confident about not only their Welsh, British, white culture, but also their Jamaican, black culture. Both of those can feed into them being confident, happy and successful people.

How did your own parents teach you about black history?

My parents were very focused on the idea of education as a tool that could not only boost you in terms of self-worth and self-confidence, but also your chances of doing well in school and therefore in life. They were part of the Windrush generation. When they were born, they were British by the fact that Britain owned Jamaica. England was in a union with Jamaica before England was in union with Scotland so that’s how long the tie between England and Jamaica is. Coming to England, some of the white people were very friendly and lovely, but some were the opposite and I can only imagine what they went through.

"My mum was a nurse and she told stories of how she had patients rubbing her skin to see if the colour came off."

They were very aware that I needed educating on these things, and I needed confidence in who I was. Whenever there were documentaries on, whatever I was watching was turned off and we would turn over to the documentary. They also bought the family encyclopedias – as soon as you buy an encyclopedia they go out of date, nevertheless I was encouraged to read those and learn about different things. One thing I remember is, when there were adverts for charities, where you see African children starving, my dad would always turn over the TV. He didn’t want us as children to cultivate the image of black people as just starving. He was very aware that the only images of black people on TV were starving babies which wasn’t very good for our mental health.

Did your parents feel proud to be British?

Yes. On forms where you had to put down your ethnicity, my dad would always put black British. Even though he very well knows he was from Jamaica. When you think about it, he’s been black British since he was born in Jamaica. Jamaica was deeply British by the fact it was owned by Britain for centuries. It makes me laugh when people complain about immigration, because historically, the worst immigrants were the Brits. They didn’t just get drunk and eat chips all day – they killed people.

I was listening to you read ‘Triptych’ in which you condemn Breckon Town Council’s blue plaque to Thomas Phillips, the slave trader. Have you been encouraged by the efforts of so many people to remove statues of racists and colonialists?

A week after George Floyd died – before the Colston statue got toppled – I got stopped by the police in this little place called Cwmffrwdoer. They were following me in a blacked-out BMW, it was not a marked vehicle, so I knew someone was following me but I didn’t know who. It was a relief, yet a fear that the police stopped me, but here’s the question that they asked me: "Excuse me sir, are you lost?" Now when was it the police’s job to follow someone and ask them if they are lost? Is that what the police should be doing? Or should they be going and finding some criminals? My point to all this is, it’s all very well toppling statues and taking off plaques and so forth, but that’s not going to help this structural issue that we’ve got in Britain. The idea of people coming together in solidarity to say there are certain things that humanly we feel are wrong and shouldn’t be happening – that is really encouraging, but there’s a long way to go. These policing issues have been going on for decades. When Stephen Lawrence was murdered and we had the MacPherson inquiry, Sir William MacPherson pronounced that the Metropolitan Police was institutionally racist. That should have been a catalyst to go, ‘We’re going to look at ourselves, we’re going to sort our system, and we’re going to continue to have these checks and balances over the coming years to make sure we don’t slip back into old ways.’ The statues are symbolic, but the deeper work needs to be done. People argue it’s erasing history. Well, actually, with Captain Thomas Phillips’ blue plaque, you can get his voyage journal – where he talks about his slave trade – on Google Books for free. Statues aren’t educational, they are monuments honouring certain people and we shouldn’t be honouring the slave trade.

What else are you working on at the moment?

I’ve been writing villanelles. They’re a very musical verse form used in English language poetry. That repetition gets a lovely musicality. A lot of the things I discuss are very modern topic matters, but I’ve been using this very traditional verse form to talk about them because these topics are British – they’re not white topics or black topics – so I’m going to use a British verse form to push these ideas forward.

What are you reading, watching and listening to?

What are you reading, watching and listening to?

First of all, if you haven’t seen I May Destroy You, it is sensational. What I love about it is that it is so female-centred. It’s also so modern; it really tackles the idea of consent for heterosexual people, for gay people and others. There’s also a great book called Don’t Touch my Hair by a mixed-race Irish writer called Emma Dabiri. It’s almost a social history of black people but from the angle of their hair. We all have that commonality in that we can all talk about our hair but if you look through the lens of Afro-textured hair it’s really fascinating. I’ve also been listening to a lot of grime music. I’ve never really been into grime, but I’ve got a friend from Bournemouth who knows everything there is to know about it. Lastly, there’s a recent poetry volume by a lady called Romalyn Ante who is a specialist nurse practitioner. Her book is fantastic. It’s one of those poetry reads that sucks you in. It’s comfortable and uncomfortable at the same time.

What do you think about the government decision to make poetry optional for GCSE students next year?

It’s like the government is signalling that what they really want to teach kids are those marketable skills that make millions of pounds for the government. Poetry is never going to be that, however in terms of things like wellbeing, it’s very well known that the arts in general – whether it’s music, dance, drama, or poetry – are really great for people’s mental health in terms of encouraging deep meditative thinking about themselves, others and the environment around us. I know that for myself, when I’m thinking most deeply is when I’m reading a poem or listening to some music. These are the kind of things that poetry and other art forms encourage. Other subjects like science and maths are more money-generating, but there are other reasons why we educate children.