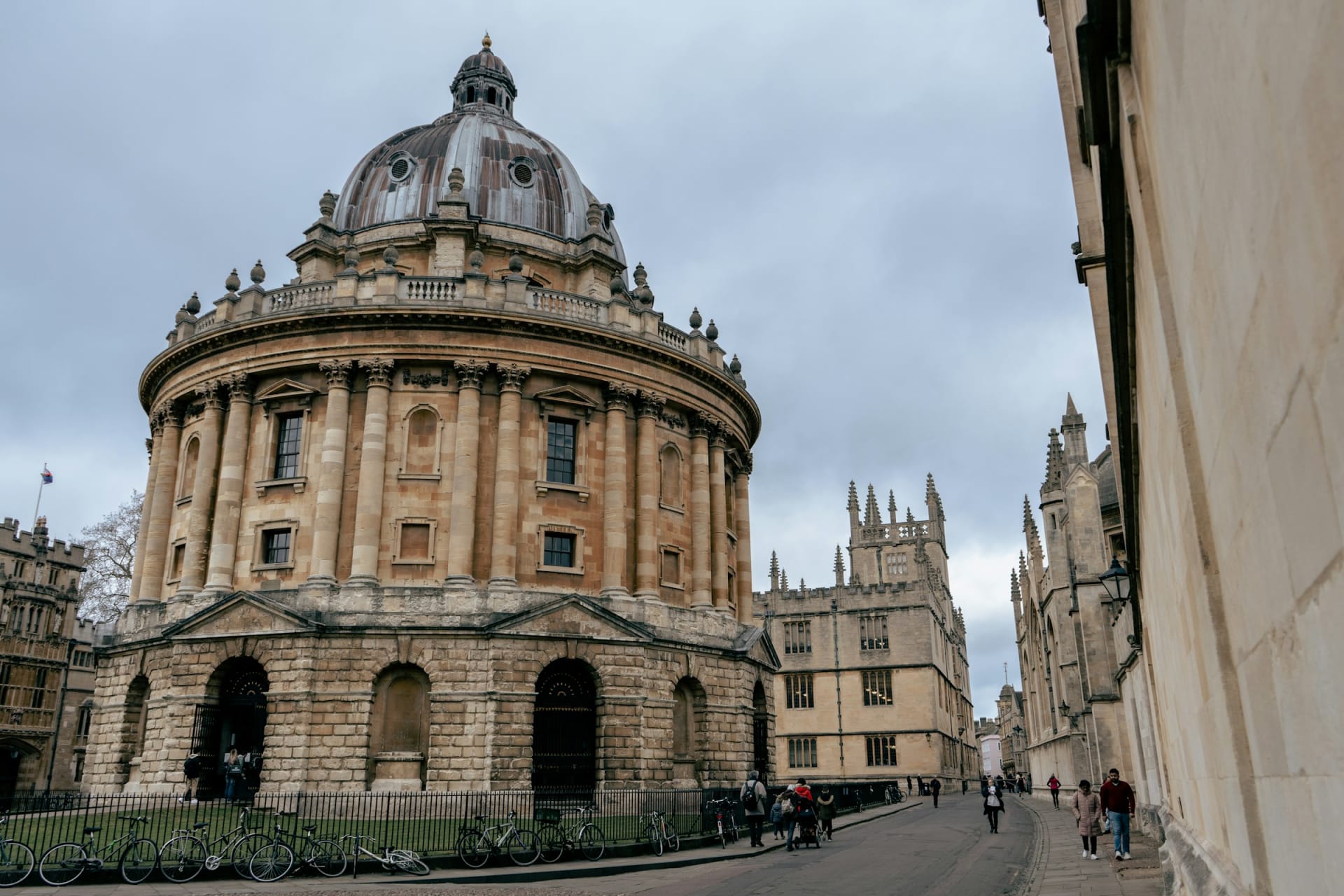

As you drive out of Oxford towards Yarnton, solar panels dot the fields to your right. To your left, you may have noticed giant pylons and not given them a second thought. However, if you peel off the A road there and venture into the winding streets of the village, you’ll find the Oxford Pioneer Park, front and centre of which is First Light Fusion, who are busy trying to solve the problem of safe, clean energy.

Like many of Oxford’s Innovation Spinouts, First Light Fusion started life as an academic endeavour. Dr Nicholas Hawker, co-Founder and CEO, along with Professor Yiannis Ventikos, co-Founder and Non-Executive Director, started researching fusion in 2007. A master’s thesis became a DPhil. Simulations were performed which suggested the possibility of fusion energy through a new and unique approach, now known as ‘projectile fusion’, which involves firing a projectile at tremendous speed to fuse to atoms together. For those unfamiliar with such concepts (me), fusion is the process which powers the sun and the stars. When two atoms of hydrogen fuse they form an atom of helium. In the process, a hella lot of energy is produced. Not to be confused with splitting an atom – which we all know has devastating impact – fusion creates intense heat, safely. Scientists from all over the world have spent decades trying to recreate fusion on earth into a viable commercial source of energy. While commercial fusion isn’t powering our homes yet, First Light are getting closer with a unique and novel approach which has received global acclaim.

Like many of Oxford’s Innovation Spinouts, First Light Fusion started life as an academic endeavour. Dr Nicholas Hawker, co-Founder and CEO, along with Professor Yiannis Ventikos, co-Founder and Non-Executive Director, started researching fusion in 2007. A master’s thesis became a DPhil. Simulations were performed which suggested the possibility of fusion energy through a new and unique approach, now known as ‘projectile fusion’, which involves firing a projectile at tremendous speed to fuse to atoms together. For those unfamiliar with such concepts (me), fusion is the process which powers the sun and the stars. When two atoms of hydrogen fuse they form an atom of helium. In the process, a hella lot of energy is produced. Not to be confused with splitting an atom – which we all know has devastating impact – fusion creates intense heat, safely. Scientists from all over the world have spent decades trying to recreate fusion on earth into a viable commercial source of energy. While commercial fusion isn’t powering our homes yet, First Light are getting closer with a unique and novel approach which has received global acclaim.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Hawker’s inspiration came from the natural world: specifically the pistol, or snapping, shrimp. This species is distinctive for its massive single claw in which water is collected in the crook. When the shrimp snaps shut their claw the force is such that a bubble is formed and ‘shot’ out at any unlucky prey. The velocity ensures anything in its path is destroyed and when the bubble pops, the noise is shattering. The shrimp creates a shock wave. Hawker’s approach was to look at how the power of these shock waves could be harnessed to replicate a scalable level of energy production.

I was met in the foyer by Chief Operating Officer, Ryan Ramsey, former Captain of HMS Turbulent, a nuclear-powered submarine. His career has incorporated both military and business, at such high levels I felt faintly dizzy in his presence. Happily, he is straight-talking, personable and palpably passionate about his current role. He is all about the “simple ways to explain, educate and make people understand” something which I feared that my lack of science-knowledge would mean was utterly beyond my ken. Our conversation was littered with questions from me: “so, is it kind of like…” and him “not really, try and think of it in these terms” but never making me feel like a fool for not instantly grasping the intricacies of the physics involved.

A sense of inclusivity, pride and excitement persists: “Going into civilian works, I’ve seen a lot of mission statements but there’s always been a disparity with the actual ethos. This is the only place I’ve worked where everyone is on board with the mission on the statement. They share as much as possible and there’s zero competition. The business model means we need to be operative and none of us think this can’t be done.” And its mission? Powering a world worth inheriting.

A sense of inclusivity, pride and excitement persists: “Going into civilian works, I’ve seen a lot of mission statements but there’s always been a disparity with the actual ethos. This is the only place I’ve worked where everyone is on board with the mission on the statement. They share as much as possible and there’s zero competition. The business model means we need to be operative and none of us think this can’t be done.” And its mission? Powering a world worth inheriting.

After fifteen minutes or so Ryan checks his watch and whisks me through the office space, to the huge hanger beyond in which the fun stuff happens. An experiment is taking place and I’m being invited to see it happen.

As we hurry along to the control room, I notice a few things which take me by surprise: a ping pong table, a treadmill, stacks of board games (including Risk), bowls of fruit in the kitchen and a series of motivational A4 print-outs encouraging staff to ‘challenge negative thoughts’ by asking ‘what would you say to a friend?’ or ‘hack happy chemicals’ like ‘meditate to boost serotonin’ or ‘try something new’ to raise dopamine levels.

Turns out, trying something new is built into the contract here as each staff member is allocated ‘time out’ to work on alternative projects. In fact, the test I’m about to witness is the result of Senior Scientist and doctoral student Cristian Dobranszki’s research into pulsed power electronics. I can’t explain what that means, but standing in the room whilst it happened was a pinch-me moment; a portal, plunging me into a sci-fi movie but made human when Cristian ding-donged his xylophone to make an announcement to all staff, inviting them in to come along to watch the proceedings. Think of school secretary, Blanche Hodel, in Grease and you won’t be far off. Incongruous but very much part of how things are done here.

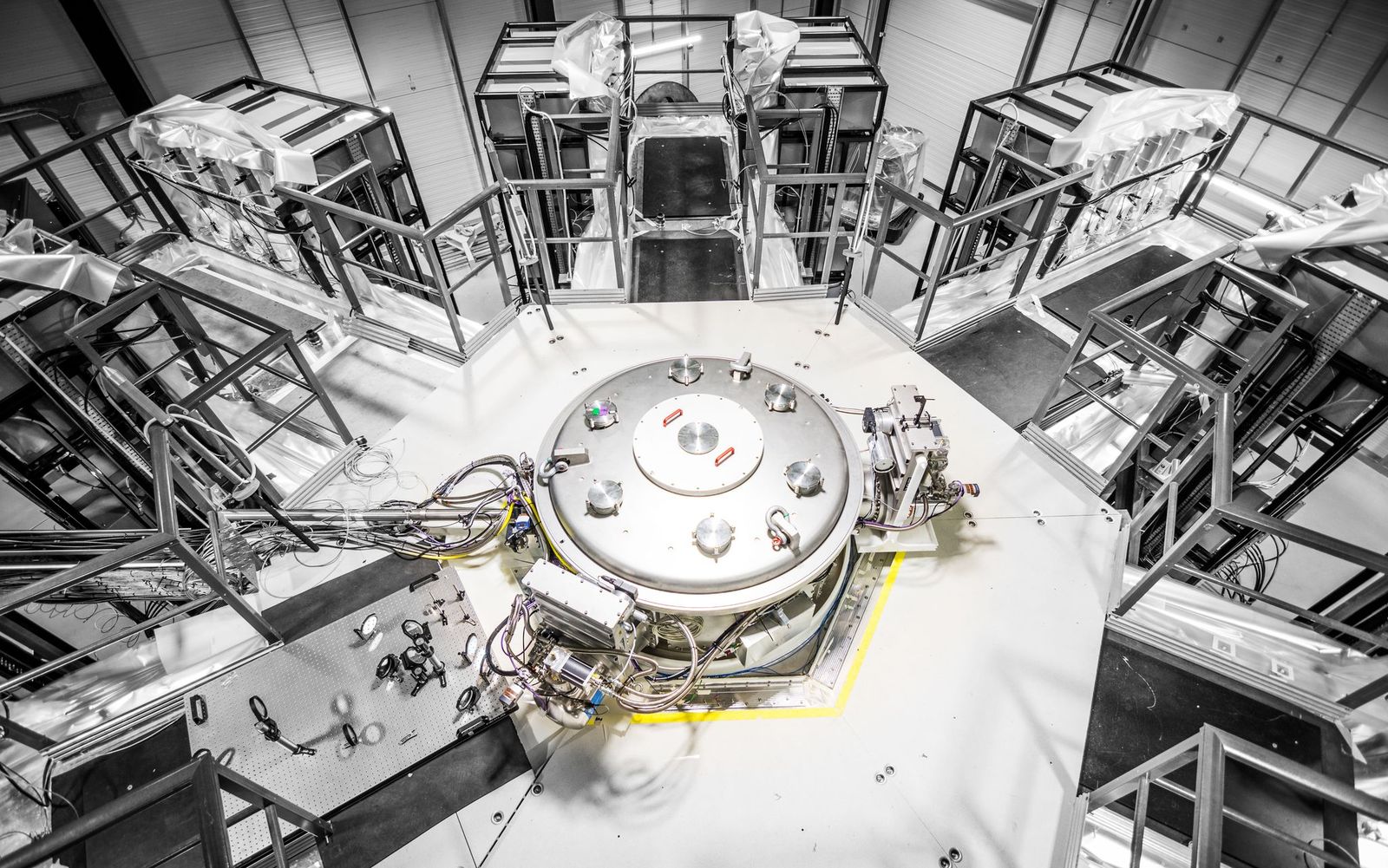

Various staffers wandered in, for the most part in their twenties and about as representative a group of young people as you might find anywhere in Oxford: one with blue hair, many with tattoos, dressed in jeans, slogan tees and hoodies. We watched as the volts charged into millions of amps. Consider your average plug carries 13 and let your mind boggle along with mine. Green lines turned red as the voltage intensified. I was relieved to see that although the many computer screens seemed to be conducting proceedings, in fact, the ultimate power lay with Cristian who was checking at each stage; calling instructions to a workmate outside the room who was performing final checks on the massive box which houses Machine 3 (M3), the largest pulsed power machine in Europe. Aha, I thought to myself, humans haven’t been replaced here quite yet.

It's a pertinent thought, as the success of First Light Fusion lies in their approach. The calculations needed to produce inertial fusion have all been the result of hundreds of simulations, produced by Machine Learning. Once likely contenders are identified, it is down to the humans to conduct the experiments that will lead to creating this new, exciting form of clean energy, right here in Oxfordshire.

It's a pertinent thought, as the success of First Light Fusion lies in their approach. The calculations needed to produce inertial fusion have all been the result of hundreds of simulations, produced by Machine Learning. Once likely contenders are identified, it is down to the humans to conduct the experiments that will lead to creating this new, exciting form of clean energy, right here in Oxfordshire.

Once we’ve all covered our ears, and a small bang has been heard, the crowds disperse. Everyone seems pretty happy, so I take it that the experiment has been a success. Ryan and I go back to the meeting room, and I try to grapple with what is happening here. He attempts to break it down for me: fusion creates intense heat, safely. At First Light Fusion they’re working to manipulate density and time to achieve temperature, and power – used to make energy – is formed by a combination of the three. The difference between fusion (what’s happening here) and nuclear fission is how the reaction to the creation of such intense heat is controlled. Fission is the method of splitting of atoms which is hard to control and dangerous. Fusion is the process of fusing atoms together, creating that same intense heat but safely, and should anything go wrong, the resulting steam simply turns to water and dissipates.

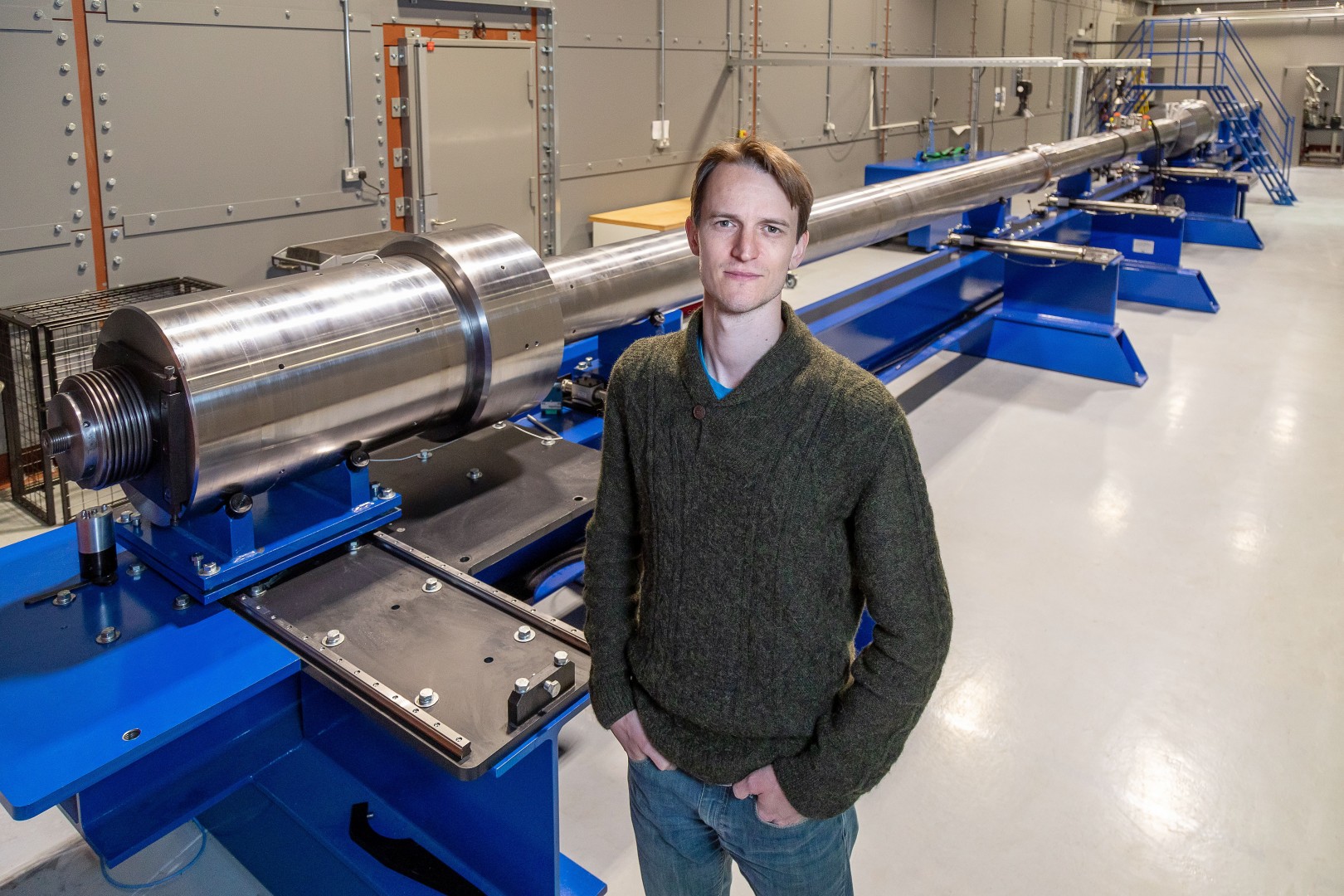

Whilst the Pioneer Park houses M3, First Light Fusion are already building its successor, Machine 4, at the UK Atomic Energy Authority’s site near Culham, the Government body responsible for fusion energy. A fusion power plant the length of a football pitch, and higher than the tallest church spire in Oxford. At this size, the energy produced becomes enough to become a real player in the energy markets. It's hard for me to grasp but eventually one of my “so, is it kind of like…” questions hits home. “So, is it kind of like you’re building a full metal jacket to house a small sun?”. Yes, kind of that. I think it’s about as near to understanding as I’m going to get, and Ryan has to leave me as the staff are gathering outside for a team photograph.

As I left, I checked Maps on my phone to find out when my bus was due. The location might have told me Yarnton but I knew I’d just visited the future.