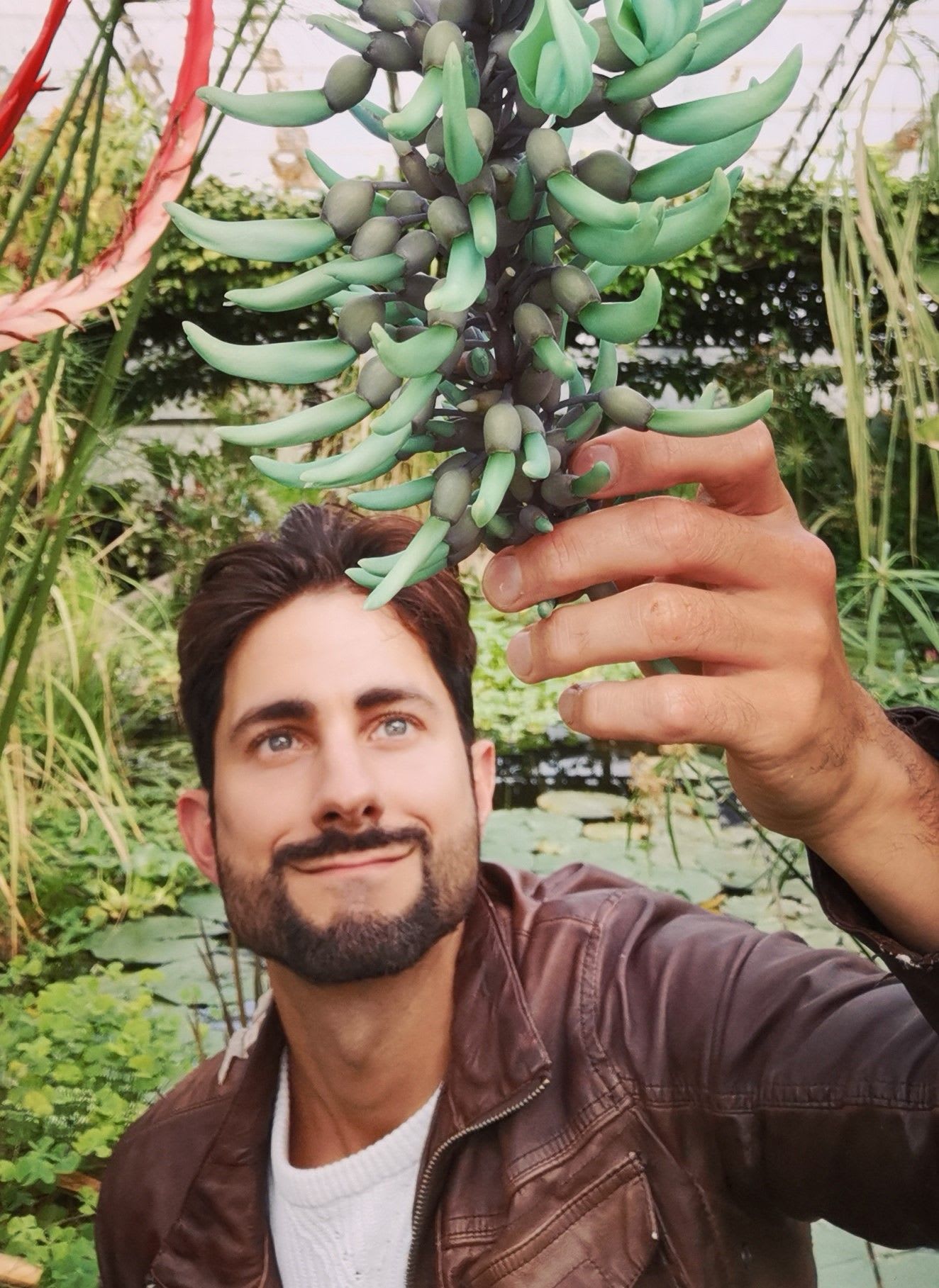

We are delighted to introduce Dr Chris Thorogood – Deputy Director and Head of Science at the Oxford Botanic Garden and Arboretum – who each month, will share with OX a carefully selected plant from the Botanic Garden’s extensive range. Not only do we have his engaging descriptions, but also examples of his work in the form of these exquisite illustrations.

‘Desert hyacinths’ (genus Cistanche) are some of the most astonishing plants I know. These botanical denizens of the desert grow across the desolate tracts of Asia and North Africa, where they sprout from the bare earth and sand. Leafless, and devoid of chlorophyll, these ‘plant pilferers’ are parasites that extract their nutrients from the roots of desert shrubs called saxauls and tamarisks. There’s nothing quite like stumbling across a desert hyacinth erupting out of the barren, seemingly lifeless desert. It’s like an explosion of colour.

Some desert hyacinths are traded around the world for herbal medicine or have historical importance as food plants. They have all sorts of perceived ‘trophy’ attributes (properties reputed to bestow longevity, stamina and even sexual vigour). Indeed desert hyacinths have long been a source of traditional herbal medicine, particularly their large, fleshy underground stems. In Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM), the plants are harvested and traded as products called ‘Rou Cong Rong’ or ‘Guan Hua Rou Cong Rong’. The plants have been used in China for more than 2000 years and they are still valued today as tonic herbs (functional health foods).

But despite the importance of these curious plants, little or nothing is known about the biology of most species, and they are difficult to identify correctly or cultivate. Together with scientists at the University of Reading, Royal Botanic Gardens Kew, and institutions in China and the Middle East, our research at Oxford Botanic Garden seeks to unravel complexity in this overlooked but important group of plants. Our work seeks to understand their species relationships: because if we don’t understand the diversity of species that exists, how can we adequately use or protect them?

Once we know more about the secret lives of desert hyacinths, we may be able to realise their untapped potential at a time of urgent need. They are now farmed successfully at scale in China to supply traditional herbal medicine at low cost. And there’s more: desert hyacinths can be grown alongside shelter forests which we need to plant to halt land degradation - a growing problem across the world’s deserts. Yes, these plants are more than explosions of colour in the desert: they are beacons of hope.