"Perhaps among those who took to the greenwood in old time there had been two men like himself — two. At times he entertained the dream. Two men can defy the world." EM Forster, Maurice

A confession: initially, this article was meant to be about my research into the real queer history of the Edwardian era, and how that research informed my own books. I am a writer of fantasy and romance foremost, and other genres (historical fiction, murder mysteries) only as necessary to create a wonderful playground for the first two. I'm not a historian – I write sex scenes and magical adventures! I'm also a scientist: the last time I attended a class with 'history' in the title, I was thirteen. Then I remembered that I had, in fact, done quite a lot of research for my trilogy, but much of it was in the form of reading other books. So, I wondered: could I write about Maurice?

EM Forster's Maurice was written in 1913 and published posthumously in 1970. It is a novel entirely about the experience of being a homosexual man in Edwardian England. It features a romance that crosses class boundaries to an extent that the time period would have found extremely scandalous (even apart from the whole gay aspect) and it ends happily. In fact, it's known as one of the earliest queer romances in Western literature to do so.

I think Forster is a wonderful author, with a knack for sympathetic but merciless observations of his characters' foibles and inner states, and I adore Maurice. If you can find an edition with the author's 1960 afterword, in which he writes poignantly on how societal attitudes have changed since the book's creation, I wholly recommend it. There's also a 1987 film adaptation starring James Wilby's floppy hair, Hugh Grant's neurotic little moustache, and Rupert Graves' bum.

My own books are about queer people living in a slightly alternative version of England in 1909: the slightly lies in the existence of a hidden world of magic-users. Everything else about the society of the time – including its attitudes towards queer people – is the same.

Every era of queer history has its traumas. My first exposure to queer-centric media, formative in my own coming-out in my teens, was the TV show Queer as Folk (US version; apologies). It had soap-opera-worthy relationship dramas, and friendships, and a great deal of sex, silliness, and dancing. All of those were a scaffold for plotlines about problems facing the queer community in the early 2000s, such as HIV+ stigma, and the fight for marriage equality. Community being the operative word there.

Maurice, set a century before Queer as Folk, is about the experience of queerness without community. About knowing yourself to be different but for a long time being unable to name how. It's about internalised homophobia, and the awful pressure of being something that society and church and family and friends all do not want – and cannot fathom – you to be.

And, it shows with ghastly effectiveness the terrible soul-chasm of loneliness that comes with this: the miserable desire to contort and suppress your true nature, if that means not being alone. There are glimpses of potential community within the book, but Maurice is not at a point where he can recognise, value, or be anything but repelled by, more overt or flamboyant versions of queer masculinity. So, he turns away.

But he does have a stubborn streak and – once he's waded through various trials – a persistent longing to find a life-defining love, a partner in joy and desire. As the quote at the top of this article shows, he too finds himself casting glances backwards through history in search of fellows. An example to look to, that would say ‘yes, despite the pressures of the world, you and people like you can find one another and be happy’.

I am writing romance; all of my characters end up happily in love. I am writing fantasy with intrigue; frankly, the characters don't have time for too much agonising. They have conspiracies to unravel, and— to veer abruptly sideways into musical theatre (I am queer, after all) and quote Pippin—magic to do.

I made the very conscious decision to scrap crises of faith, uncertainty of one's sexuality, and self-hatred entirely. I used the need for secrecy to add to the 'us against the world' situation that serves a romance plot so well, and also to emphasise the exquisite surprise and delight when a kindred spirit is recognised. (In A Marvellous Light, the main characters first realise their shared queer nature because they're both familiar with an anonymous writer of gay erotica. It's not exactly catching sight of a rainbow flag pin on someone's lapel, but hey, whatever works…)

I want my books to heal the central wound of Maurice-the-character, by allowing people existing within Maurice's time to find a queer community. So I gave my characters self-acceptance and then put them on a path to being surrounded by people like themselves: a family formed by danger and adventure, but most of all by liking and by love.

We can't ignore the past. We can't stop telling stories about how hard it was – and how hard it still is – for many. Those stories are vitally important. But I'm writing for the times when we want to stretch our own hand back into the past and say: I'm sorry you were alone. Here's a dream for you. Here's a dream for all of us.

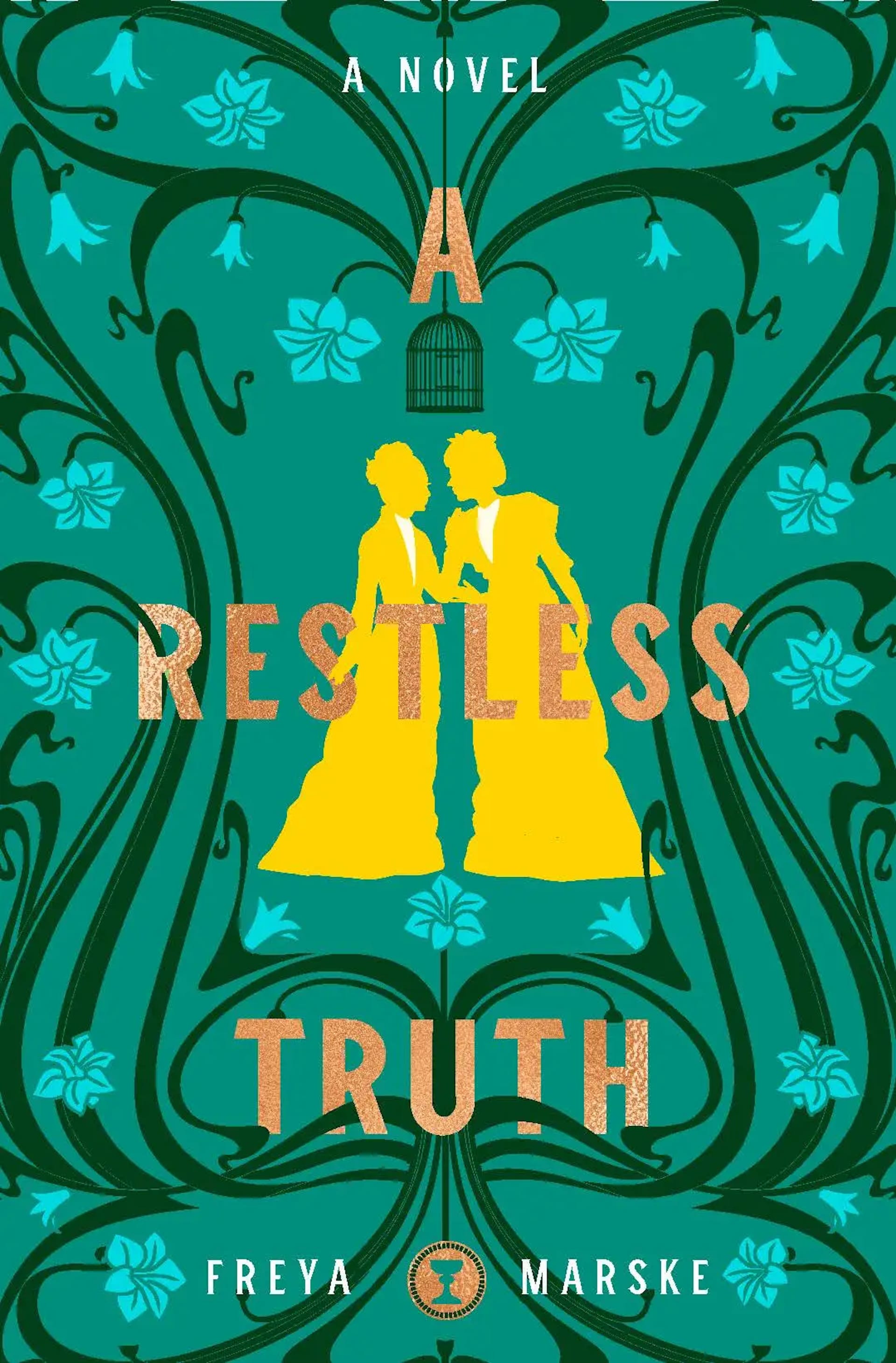

Freya Marske’s new book A Restless Truth – sequel to the instant Sunday Times Bestseller A Marvellous Light – is a fantastic fantasy feast for the imagination.

Maud Blyth has always longed for adventure. She’d hoped for plenty of it when she agreed to help her beloved older brother unravel a magical conspiracy. She even volunteered to serve as an old lady's companion on an ocean liner. But Maud didn't expect the old lady to turn up dead on the very first day of the voyage. Now she has to deal with a dead body, a disrespectful parrot, and the lovely, dangerously outrageous Violet Debenham. Violet is everything Maud has been trained to distrust, yet can’t help but desire: a magician, an actress and a magnet for scandal. Surrounded by open sea and a ship full of suspects, Maud and Violet must learn to drop the masks they’ve learned to wear. Only then might they work together to locate a magical object worth killing for – and unmask a murderer. All without becoming dead in the water themselves.

A Restless Truth is available from panmacmillan.com and all good bookshops