Dan Vo is a Victoria and Albert ambassador and founded the volunteer-led LGBTQ+ tours at the museum. During lockdown, the museum queerator and LGBT+ History Month patron has been instrumental in #MuseumFromHome, for which he’s interviewed a plethora of museum workers. Here he talks about the initiative’s ‘one-minuters’ – minute-long videos about specific artefacts – and stresses the importance of museums giving a voice to minority groups, as their collections move online.

What is a museum queerator?

It’s a title that’s obviously a bit silly but it’s stuck. Effectively, I get to work with many collections around the country and look for the queer history in them. I tell the stories of LGBTQ+ people across places, time and culture – there’s a wealth of them contained in every single collection. We’re looking for queer stories already on display, that aren’t told at the moment or are hidden. There’s a principle three as to what we put on an LGBTQ tour (that I would do at the V&A, the University of Cambridge Museums or Amgueddfa Genedlaethol Caerdydd National Museum Cardiff. You can start with an object by a maker that was LGBTQ+, it could be the subject they’ve depicted is LGBTQ+, or it could be about the male gaze, the queer gaze or the queer eye – the community looking at something and saying, ‘we can see a part of ourselves reflected in this object, so we’ve made it part of our story.’ (I always like to start off with the statue of David because that’s a great example where all three circles on this Venn diagram intersect very neatly.)

It’s a title that’s obviously a bit silly but it’s stuck. Effectively, I get to work with many collections around the country and look for the queer history in them. I tell the stories of LGBTQ+ people across places, time and culture – there’s a wealth of them contained in every single collection. We’re looking for queer stories already on display, that aren’t told at the moment or are hidden. There’s a principle three as to what we put on an LGBTQ tour (that I would do at the V&A, the University of Cambridge Museums or Amgueddfa Genedlaethol Caerdydd National Museum Cardiff. You can start with an object by a maker that was LGBTQ+, it could be the subject they’ve depicted is LGBTQ+, or it could be about the male gaze, the queer gaze or the queer eye – the community looking at something and saying, ‘we can see a part of ourselves reflected in this object, so we’ve made it part of our story.’ (I always like to start off with the statue of David because that’s a great example where all three circles on this Venn diagram intersect very neatly.)

What would your job title have been before we reclaimed the word queer?

An LGBTQ+-urator?

Not as catchy…

Growing up in Melbourne, I felt comfortable using the word queer because there are so many organisations in Melbourne that had already reclaimed it by the early 90s – the Melbourne Queer Film Festival, Midsumma Festival. When I first arrived here about ten years ago, it was a shock for some people that I was using it so openly. It has been used more and more now, especially by younger people who feel it is a good umbrella term that they’re comfortable with.

How are you coping with lockdown?

I’m on my own, but I’ve been doing a Twitter Live every day for #MuseumFromHome. That’s keeping me sane and engaged with lots of different museum professionals. It’s helped with the routine as well; it gets me out of bed, showered, I put on my undies… the important things in life continuing. I need to do a shout-out to Sacha Coward who’s inspired so many people to do the one-minuters – contributions from all around the world from all sorts of different collections.

You did your own one-minuter about the Speedo, an interesting item with a queer history.

It is one of the most iconic pieces of Australian fashion and I challenge you to think of a Pride somewhere in the world where a Speedo is not present. It’s visually such a striking piece of fashion and it was created by a gay man, Peter Travis. He was a bit of a polymath; he wasn’t just a fashion designer, he was also a ceramicist among many things. He was the first Australian to have work collected by the V&A – something he was incredibly proud of.

What impact has Covid-19 had on your industry?

There are a lot of us museum freelancers whose bread and butter is audience engagement. Until recently that has very much been focused on face-to-face; get people into the museum and engage on that level. There are many of us now who have to quickly pivot because suddenly months of well-planned work has halted, so a lot of us are recalibrating at the moment. But the principles of engaging with somebody face-to-face are very much the same digitally. We’re also there at the moment as a reminder to the organisations that at the heart of everything we do, we still need to think about diversity and representation. It might be quite easy for an organisation to go, ‘here’s a splash of all the things you can still get at home’, but it’s still important to cover stories of LGBTQ+ people, but also intersectional elements like people of colour, working-class stories and people with disabilities. As collections suddenly go online and aim to engage digitally, it’s important we remember that the minority voices should be given a space and amplified as well.

You’re now a patron of LGBT+ History Month.

Yeah, and that’s a huge honour and one that I’m going to do my best to uphold. About the same time I started the tours at the V&A, I was involved with the team at Schools OUT who founded LGBT+ History Month 15 years ago. I was involved with a national museum that was recognising LGBTQ+ stories and heritage, and working with Schools OUT which is about going into schools and challenging homophobia, biphobia and transphobia through education. My work with LGBT+ HM has often been behind the scenes, helping with things like media strategy and developing resources. It’s a really amazing grassroots organisation and Sue Sanders is amazing as the figurehead. It has inspired so many different organisations to open up their minds to the way in which they engage with LGBTQ+ history.

Matt Smith has his installation at Oxford’s Pitt Rivers, Losing Venus, about the effects of British colonialism on queer lives around the world – we can’t wait to see it when the museum reopens.

I am so glad you mentioned it – I was with him on the opening night. Matt’s work is really enticing and comes with real academic heft. The ceramics in Losing Venus are really remarkable – I think that’s what he’s best at making. You want to get up close and have a look, then you’re suddenly almost slapped with the topic. You go away and think really deeply about the consequences of things like that.

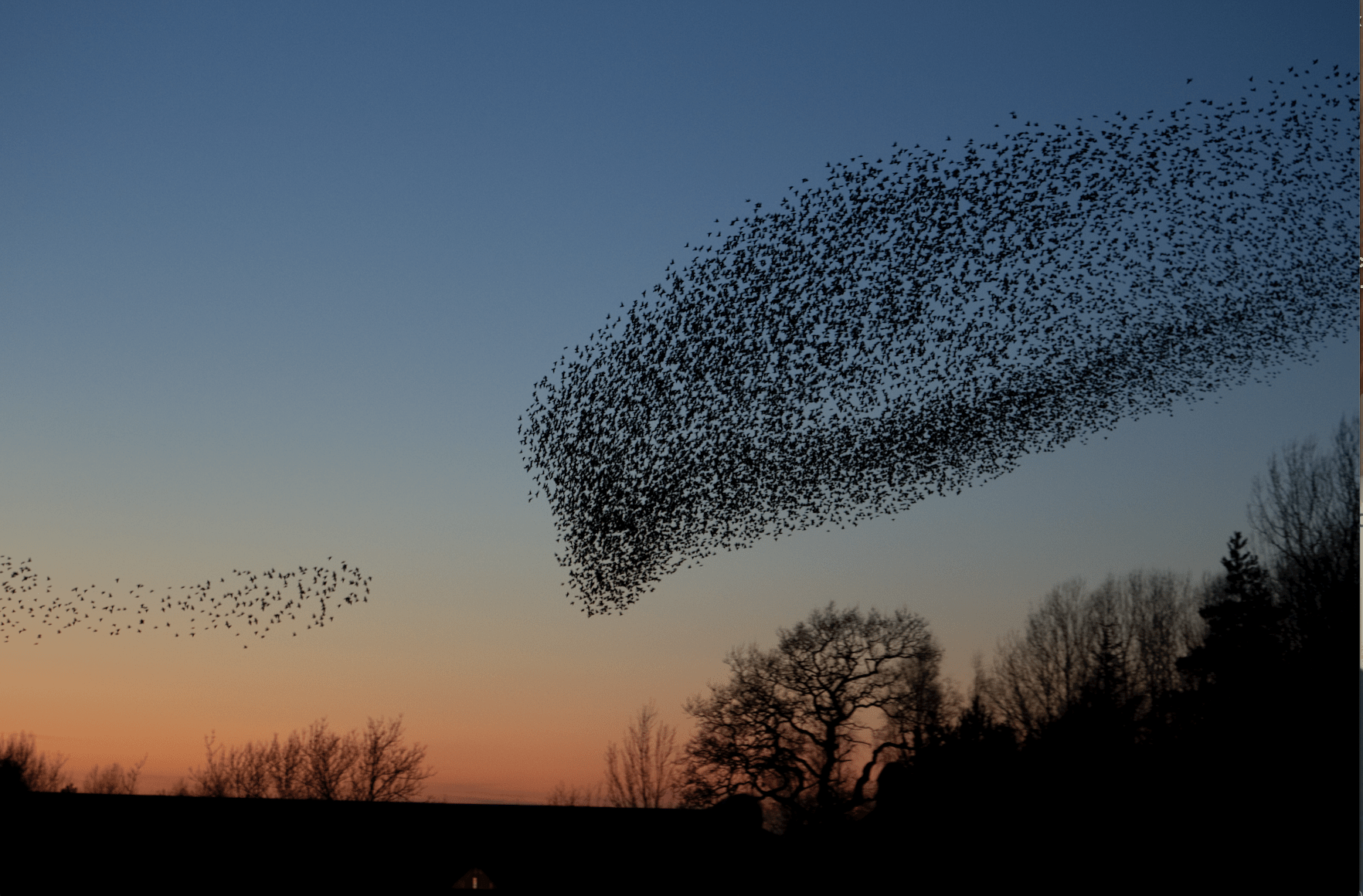

Photography © William Pearce

Also, when Pitt Rivers does reopen, one of the things worth visiting Oxford for will be the Beyond the Binary exhibition. The team have worked really hard for over a year to pull everything together and it really does look at that idea of intersectionality. There’s going to be a telephone box in the trans colours [a nod to the city’s pro- and anti-trans sticker conflict]. That represents an ongoing challenge that is there right now. The museum has pinned its colours to the mast: we have said we are pro-trans. In fact, the trans colours were projected onto the museum’s façade at one point. A collection like the Pitt Rivers – which you usually associate with old things from around the world – can still have a really important role in the contemporary debate, saying, ‘we want to support trans people. Trans men are men. Trans women are women.’ For many years afterwards, museums will look back and say that was a good example of how to do museums right.