Josephine Trotter is up in London for her weekly life drawing class. Throughout her long career she has kept up this essential practice with a discipline which defines both her character and her paintings.

But first, a boiled egg. With a flash of immaculately manicured scarlet nails, she removes a feather from the shell of the egg which was laid by one of her hens back in the Cotswolds. Five minutes later she emerges from her capsule kitchen. She stops in her tracks. “I might paint that one day,” she says, fixing her gaze on the balcony doors overlooking the Chelsea garden square below. She has been coming to this flat for 60 years but it is as if she is seeing the view for the first time, allowing me to glimpse the “absolute bolt in the head” she experiences when reacting to a motif in nature.

Trotter is just back from the Tate Modern, where she saw the Cezanne exhibition for the sixth time. Cezanne has been an enduring influence, the artist whom she admires most. As a student she was taken by Maurice Feild, a teacher at the Slade closely associated with the Euston Road School, to the British Museum to copy Cezanne’s original drawings. “They were pulled out of drawers and put in front of us,” she recalls. And she is still learning. “I gleaned more every time I went back [to the Tate] - not to see the whole exhibition but various paintings, to study the way he puts paint on, the deliberate brush strokes, his innate sense of structure. He is particularly strong on negative spaces.”

Trotter is just back from the Tate Modern, where she saw the Cezanne exhibition for the sixth time. Cezanne has been an enduring influence, the artist whom she admires most. As a student she was taken by Maurice Feild, a teacher at the Slade closely associated with the Euston Road School, to the British Museum to copy Cezanne’s original drawings. “They were pulled out of drawers and put in front of us,” she recalls. And she is still learning. “I gleaned more every time I went back [to the Tate] - not to see the whole exhibition but various paintings, to study the way he puts paint on, the deliberate brush strokes, his innate sense of structure. He is particularly strong on negative spaces.”

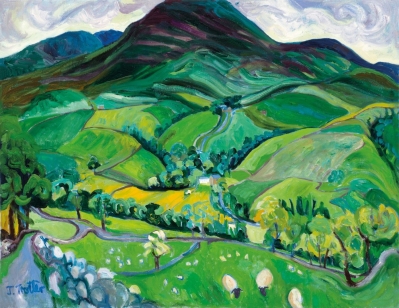

Trotter was especially drawn to Cezanne’s paintings of Mont Sainte-Victoire, each one different. Her equivalent iconic landscape is Brailes Hill, the second highest peak in Warwickshire, which she can see from her home outside Hook Norton, and to which she returns again and again. “Brailes Hill is hugely important to my work because I have painted it from every angle and in every light’” she says. “It’s part of my life, really.”

Although Trotter has painted all over the world, it is the landscape of the British Isles which she finds most compelling. “I don’t have to have a clear blue sky as occurs in Europe or India because I like the way the clouds skitter across the landscape and the changing light which is reflected, really, from the clouds. I love Worcestershire and Herefordshire – the red brick which is intrinsic to that countryside against the greens, like a beautiful Jersey cow.” British stock against British landscape is, she believes, “second to none” and another subject close to her heart is churches - “the jewels of Great Britain”.

“I am very interested that Great Britain is very small compared to other countries and yet every bit of it is totally different. Wales is strong and hilly; Scotland more misty and a different light. Northumberland is very powerful and the shapes of the fields and hills are different again in, say, the Marlborough Downs. I like the valley where John Nash painted the River Stour. The fact that he lived there and painted there at Wormingford, that can’t help but seep into your soul.”

“I am very interested that Great Britain is very small compared to other countries and yet every bit of it is totally different. Wales is strong and hilly; Scotland more misty and a different light. Northumberland is very powerful and the shapes of the fields and hills are different again in, say, the Marlborough Downs. I like the valley where John Nash painted the River Stour. The fact that he lived there and painted there at Wormingford, that can’t help but seep into your soul.”

Trotter’s feeling for landscape is grounded in human anatomy, the contours of the countryside to her mind akin to large nudes. She remembers a particularly joyful occasion painting the Blue Howgills, in Cumbria, which was “really like doing a big life painting”. Here, again, her life drawing – first taught to her by the distinguished post-war artist Euan Uglow – comes into play. As Ann Dumas, Curator at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, and Curator of the Museum of European Art at the Museum of Fine Arts, in Houston, Texas, puts it: “Spontaneity is everything yet it belies [Trotter’s] thorough grounding in technique and innate sense of organisation and structure, which underpin the strength of her paintings.”

Trotter paints en plein air at a single sitting, and never reworks the canvas in her studio afterwards. Lunch is a can of Guinness. Painting for her is a physical business and such is the level of absorption that she pays no attention to sitting properly or breathing. After about seven hours she “can hardly move.”

Whether it’s the cows outside her kitchen window or the windfall apples beneath her feet, Trotter doesn’t have to go far for her subjects. She has just finished a small painting of leeks for the Chelsea Arts Club’s charity auction (title: Animal, Vegetable, Mineral). “I love painting leeks,” she enthuses, “but if you go into a shop they’re horribly truncated both ends and I wanted wild and hairy both ends.” Luckily FarmED, a nearby centre for farming and education, was able to dig some up for her. She shows me the painting. As ever, her use of colour is sensational. “I think that it would be wonderful to do up a room totally leek-coloured,” she says. “You start from pale creamy white to almost white and go through to slightly stronger yellowy greens and then you get into the beautiful blue – there’s a lot of Prussian blue in the wild tops of the leaves that spring out all over the place.”

It was at Chelsea School of Art, from which she graduated in 1961, that Trotter discovered colour. Feild had insisted on a very limited palette and taught her to grind her own paint but, at Chelsea, “colour came bursting out of [her]”. She found inspiration in the early 20th century colourists – Matisse, Derain and the Fauves - and recalls the guilt she felt when she bought five different green paints in tubes for the first time rather than mix her own. And then, of course, there is Van Gogh. “His last years were his best - so joyful despite his mental anguish,” says Trotter, whose own paintings are often appreciated for their joyful quality.

It was at Chelsea School of Art, from which she graduated in 1961, that Trotter discovered colour. Feild had insisted on a very limited palette and taught her to grind her own paint but, at Chelsea, “colour came bursting out of [her]”. She found inspiration in the early 20th century colourists – Matisse, Derain and the Fauves - and recalls the guilt she felt when she bought five different green paints in tubes for the first time rather than mix her own. And then, of course, there is Van Gogh. “His last years were his best - so joyful despite his mental anguish,” says Trotter, whose own paintings are often appreciated for their joyful quality.

Last summer Trotter had her 25th solo exhibition in London but she is not complacent. Perhaps her secret lies in constantly seeking out new challenges. After watching the Queen’s funeral, she transposed the emotion she felt onto canvas and released a limited edition print; she recently staged a white still life in her studio as an exercise in observing the subtle differences in all the whites (“the same as you get with all the greens in the landscape”); she spent last weekend painting a large canvas of the copper stills at nearby Cotswolds Distillery.

Besides her work ethic, it is Trotter’s strong convictions that set her apart: whether she is alighting upon a particular vantage point from which to paint a landscape or naming her Scottie dog (Presley), she is decisive and emphatic. “It’s a terrible crime,” she declares with characteristic certitude, “if you are given a talent, whether it’s music or writing or painting or teaching, and you don’t use it. I’ve always felt I have a talent but it comes from out there, passes through me and then, when I die, goes on to someone else.”

It is time for her life drawing class. With a flourish she gathers up her canvas, slings a bag of paints over her shoulder and sets off in her fluorescent trainers. “Lots more work to be done.” she declares.