Dean Atta rings in the morning after a drag show at Kings Place, “a bit on the comedown from it. You get a lot of adrenaline when you do drag performances,” says the spoken word poet, “and then afterwards you’ve got the makeup on your eyes that you didn’t wipe off, I’ve still got nail varnish on – I’m like, ‘Oh yes… that was me yesterday.’” My nails are also painted, not because of a drag performance though, I don’t have that bravery. “What colour?” Red. “Nice, that’s pretty brave – maybe not in the workplace, but on public transport…”

He’s selective about when he does drag. “It was ok yesterday, but a previous time I experienced dysphoria afterwards and just felt a bit strange for a while. I have to get a handle on what that is and what that means for me, so I don’t do drag at every performance, I have to build myself up to it and make sure I’m going to have people there with me, who will look after me if I don’t feel so good after. I feel good when I’m doing it, I feel amazing, on top of the world, so empowered. People tell me I seem more confident, more funny, more of me, I guess. But is it me? Am I channelling something that isn’t me? I don’t know – drag raises a lot of questions, for me anyway.”

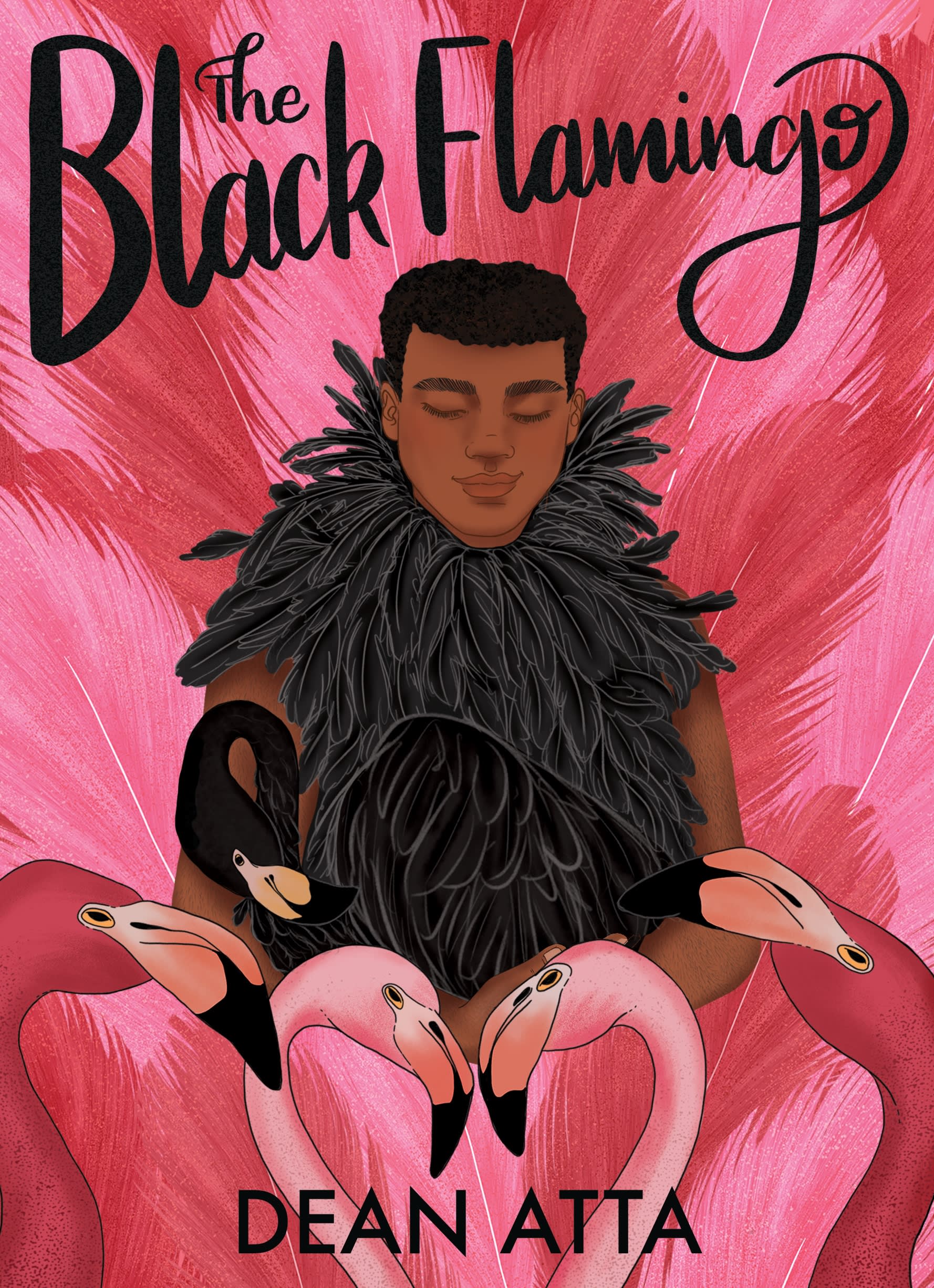

Last night’s gig was The Black Flamingo Cabaret, which shares its name with his first novel. Written in verse, The Black Flamingo follows a black gay teenager called Michael, as he discovers his true self. I listened to it on audiobook, as read by the author, which he says is the best possible way to experience it, “other than me coming there and reading it to you in person”. He recommends those reading off the paper, “even if it’s just a few pages”, to do so out loud. “You hear more, you appreciate more of the rhythm, and the words come across even stronger.”

The novel is “somewhat autobiographical” though Michael is a teen now as opposed to in the nineties and early noughties. This means he has more freedom, role models and vocabulary with which to address gender, sexuality and the intersections of being a queer person of colour. “I didn’t know what intersectionality was when I was a teenager, a teenager today is equipped with more tools and language to deal with and embrace their difference from the mainstream society.”

At the end, Michael performs in drag, something Atta didn’t do until he was in his thirties. “I was just scared,” he says. “Maybe I was scared of femininity or what would happen if I expressed that. I was scared of violence more than anything, the violence I might experience if I were to be too feminine in the wrong place, because the world is not only homophobic, it’s misogynistic.” He gave Michael fewer fears and more fearlessness than he had at that age.

While his character’s first drag show was at a university night, his was at Royal Vauxhall Tavern, part of the Art of Drag course led by Michael Twaits. “It was such a powerful experience” he felt he had to write about, but in a university setting for a story far neater than his own. “Michael’s is much more like a fairytale, that’s what I say in the prologue: ‘This book is a fairytale.’ No one’s life will probably go this well but we can hope,” he laughs, “we can hope.” It’s quite traditional, I point out, to end a book with a performance. “Well, I’m hoping it’s going to be made into a movie, so I just thought that would be the best ending,” he says, the latter half of the sentence slightly obscured by more of his laughter. “I’m waiting for Netflix to call.”

The novel has taken him into schools in Sydenham, Southend and Bath, to “really receptive, teachers, librarians, and students”. He tells groups about how he started writing, at what point it became his profession, his spoken word performances, and The Black Flamingo from which he also reads a little to them. He’s then open to questions about the practice of writing or indeed the topics his writing covers, “whether it’s racism, sexuality or drag”. They’re smart questions, he says, there are those who will stay behind afterwards to ask him things they didn’t want to in front of their peers, and “teachers are really moved by how engaged everyone is. I’m glad schools are making space for these kinds of conversations, and librarians and English teachers are excited to have books like this in schools. It shows there’s a readiness for this and young people – regardless of their own sexuality – find it interesting, love a good story and will be open-minded to things. That gives me lots of hope for the generation I’m writing for.”

It seems to counter the less than encouraging attitudes aired during the Birmingham LGBT lessons row. “Someone reminded me recently that things make the news because they’re exceptional,” he responds. Outside of the city in the Midlands, “people are getting on with giving kids these important lessons and insights into how other people, or people like them, live. We hear about Birmingham, and any protests, because they’re not happening everywhere and they’re not happening all the time.”

He’ll be in Birmingham this month for SHOUT Festival (“Bring on the protest, nah, I’m joking”) where he’ll deliver a workshop on “creating your alter ego in poetry”, exploring mythology, superheroes and drag personas. “There won’t be any makeup or fashion lessons from me, it will all be about writing, using your imagination to write a persona that could do things you couldn’t do as yourself.” Nobody will have to read out what they pen, though participants who want to can, “sometimes you just need to write something that’s for you and you only, and that’s fine.”

In the same month, he’ll also be appearing in our region. With LGBT History Month taking place in February – themed Poetry, Prose and Plays – it launches mid-November at Pitt Rivers and Museum of Natural History. Here, his plan is to perform, “but there’s a nice section in the book which namechecks lots of black queer writers and performers – I may talk about some of them, what they mean to me personally. There are so many people that have paved the way for me. When you get some relative success, people think you’re the first of this or that, and we all know that’s never true.” There’ll be those in that list, he says, whose queerness has not been included in their history. “You’ll be like, ‘Oh, they were queer? That’s not really in their work.’ No. Whoever published them was selective about what they published.”

He uses the word queer, as I do to describe myself and members of the LGBTQ+ community, in the name of reclamation. I’ve heard it said that this is no different to a black person using the N word, but it’s actually very different, isn’t it? “I don’t know,” he doesn’t hesitate. “It’s different from our point of view, as those who have reclaimed.” That might not be the case for “those who had it thrown against them, along with fists and kicks from homophobes”.

I’ve asked him about this in consideration of his 2012 poem, ‘I Am Nobody’s N*gger’, where black artists’ use of the abhorrent term is condemned. It did apparently change minds. “People came to me and said, ‘I’d never thought about it that way and I’m going to stop using it,’ and several rappers and poets that were using the word did stop around that time as well.” But he’s “kind of given up on the N word. I think, ‘Let people have it.’ I’ve moved past that. There are bigger fish to fry. It’s about dealing with the structural institutional racism rather than in-fighting with black people.”

He’ll still not utter the word (“nothing would convince me to”), but so long as black people aren’t directing it at him, “you’re free to say what you want about yourself or amongst your friends. I just think people should not be surprised when white people then want to use it too, and I think that’s really the worst use of the word; even if they’re trying to be in with the black people, or singing along to a song, it never feels ok. If we could eradicate that word, I’d be happy. But I think it’s quite deeply entrenched with some people now, and they have reclaimed it for themselves. It doesn’t mean they’ve reclaimed it for me.”

He’s moved house and country recently, settling with his partner in Glasgow, where the “wonderful” queer bookshop, Category Is, stock The Black Flamingo, host author events and LGBTQIA+ inclusive yoga on Saturday mornings. “That’s one of the spaces I’ve been attending quite frequently. There are also quite a few cabaret nights I’ve been going to, we recently had the Scottish Queer International Film Festival – I went to some events attached to that.” The more things you attend, he says, the more you bump into familiar faces. “The same people start popping up. I haven’t made best pals but I could go somewhere on my own and probably see someone I know, even though I’ve only been there a few months – I’m starting to feel quite comfortable.” The first time he and his partner have lived together, “it’s been an interesting move, but I think it was the right time in my life for something like this.” He’s often back in London, he’s been traveling the UK with the book, which he’ll also discuss at this year’s “very cute” Shrewsbury Festival of Literature. “I’m nesting,” he says, “but as with any good nest, you can always fly out of it. So I do, I’m still getting out and about as much as I always have, but Glasgow’s now home.”

That’s a sound enough ending for me – ready when you are, Netflix.

The Black Flamingo is out now (Hachette Children’s Group). The LGBT History Month launch takes place 15 November, Pitt Rivers and Museum of Natural History.