As First Imprints, an exhibition by Oxford Printmakers, opens later this month, Dr Jack Matthews, Museum Research Fellow at Oxford University Museum of Natural History, reflects upon the science that underpins it. “The fossils on which these works are based are natural prints in themselves. Geology and palaeontology are not just studies in time, but also process, and there are great parallels between the processes of printmaking and the way these fossils were made,” he explains. “The formation of both the fossils and the prints involved chemical changes, and the slow build-up of layers. The printmakers worked with researchers in the Museum to understand the science and to show it with artistic flair, and this exhibition is an assemblage of printing techniques and interpretations that brings these ancient organisms back to life in a fantastic and vibrant way.”

The 22 artists whose work is on show use their art to encourage the viewer to think more about the amazing story of how complex life began to unfold on Earth as told by the rocks beneath our feet. The earth is 4.5 billion years old and the first evidence of life on earth appears in the rock record a billion years later. For 2.5 billion years, life on earth was single-cellular until the appearance a billion years ago of the first multicellular organisms, albeit still on a microscopic scale. It took almost another 400 million years for the fossils of larger organisms that might have been viewed with the naked eye to be discernible, a transition which marks the beginning of the Cambrian era of prehistory. It is this transition upon which the Oxford Printmakers have largely focussed.

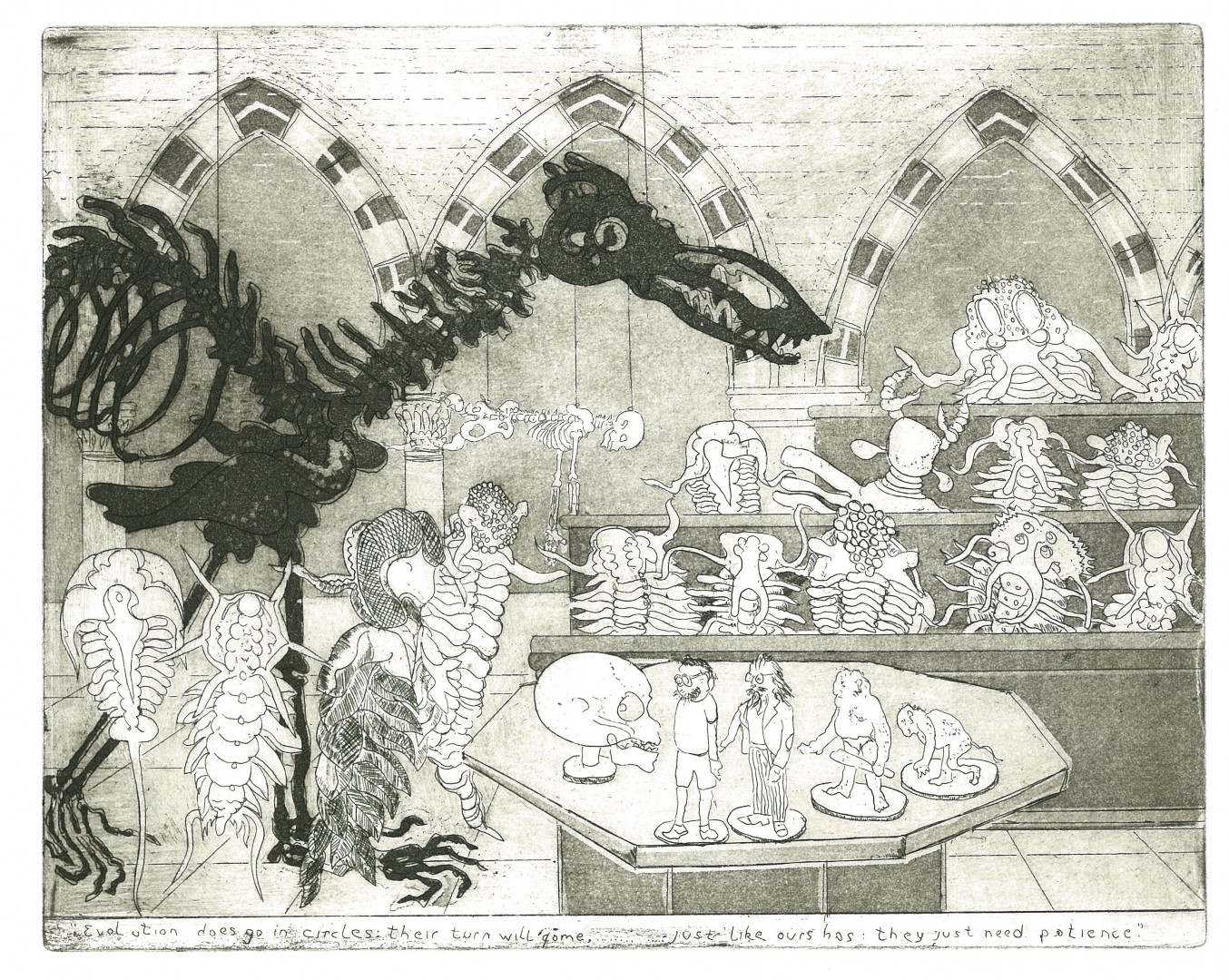

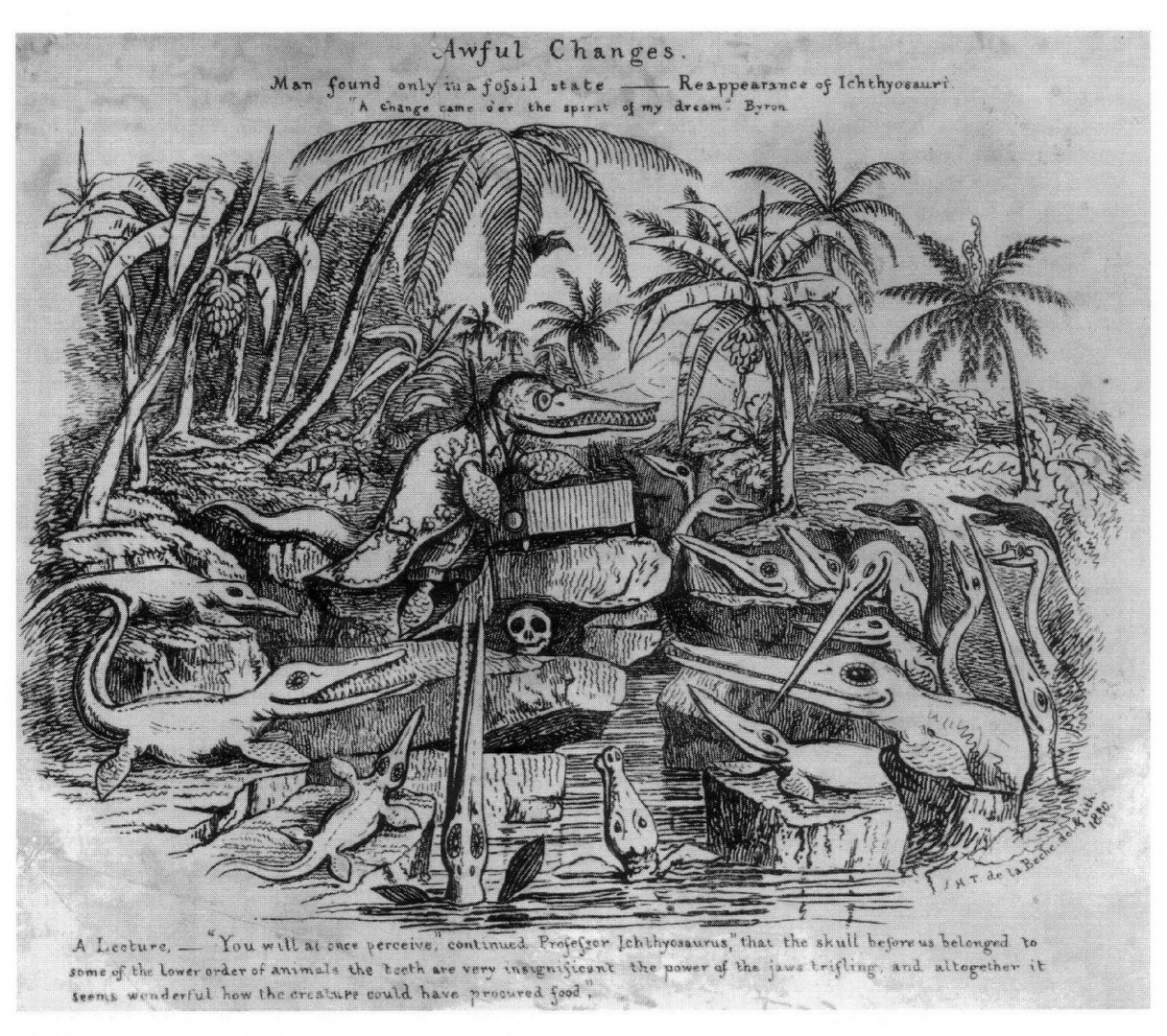

In the first few pictures of the exhibition, look out for an etching ‘Professor Trilobite’s Lecture’, a humorous role reversal of trilobites and humans. Consider the rationale behind this work and you’ll find yourself uncovering characters who lived and worked in Oxford 200 years ago, and their rivalries and debates over the key issues at the time. The print is a play on an earlier piece that showed a Professor Ichthyosaur, apparently a caricature of an Oxford University geologist in the first half of the 19th century, by his colleague Henry de la Beche. The two academics disagreed about whether time is best considered as a single-minded progression depicted in the rock, or a cyclical pattern, never reversible but regularly repeated. The Professor Ichthyosaur cartoon, itself a play on an earlier lithograph of the first geology lecture, and the new trilobite work by printmaker John Dew asks whether species that were close to extinction could come back if environmental changes occurred.

An intriguing piece by Sally Levell, the instigator of the exhibition, highlights the hypothesis of whether the globe was once a ‘Snowball Earth’ covered by ice from the poles to the equator during one or more extreme cooling events between its formation and the advent of multicellular life. In the deep blue ‘Proterozoic Glacial Sediments’, she includes a chemical equation and encourages an investigation of the changing mineral composition of the Earth’s surface. It’s a chicken and egg question apparently: does life change because of these alterations or does the sediment make-up alter because life is evolving?

Sally describes herself as a ‘hybrid’ – a geographer with a life-long love of art, an Earth scientist and a printmaker. “Rock is beautiful to look at and it has such a past and so many stories. I wanted to tell these in an artistic way that would pull people in to look and learn.”

While some of the pieces in the exhibition explain complex ideas; others are carefully-considered studies of the forms seen in the fossils, from fractal fern shapes to early fauna.

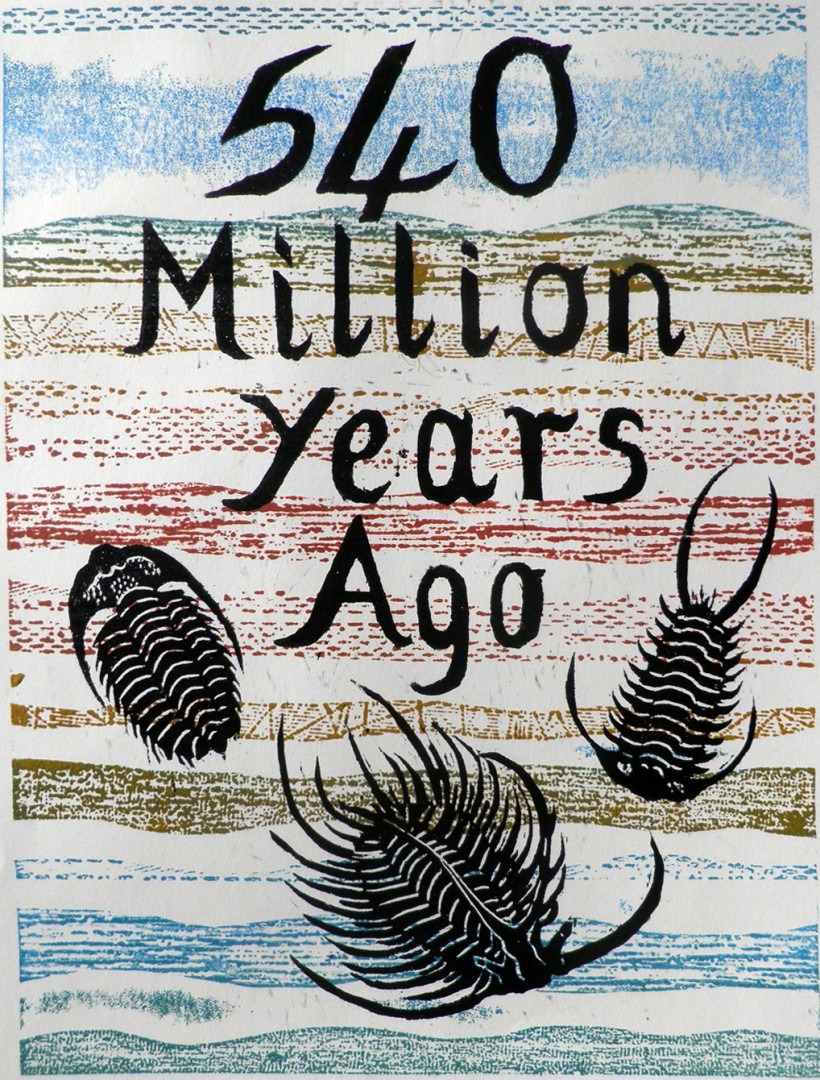

Margot Bell, most known for her prints of mythology and legend, is showing wood-cut trilobites alongside a bold statement of the mind-boggling time-line, the relief print behind hinting at the many layers of the Earth’s crust laid down over the years. “It is unbelievable that such creatures were swimming in the seas 450 million years ago,” she says. “Their complex structures show that evolution has already progressed far from the simple cell structures which were early life forms.”

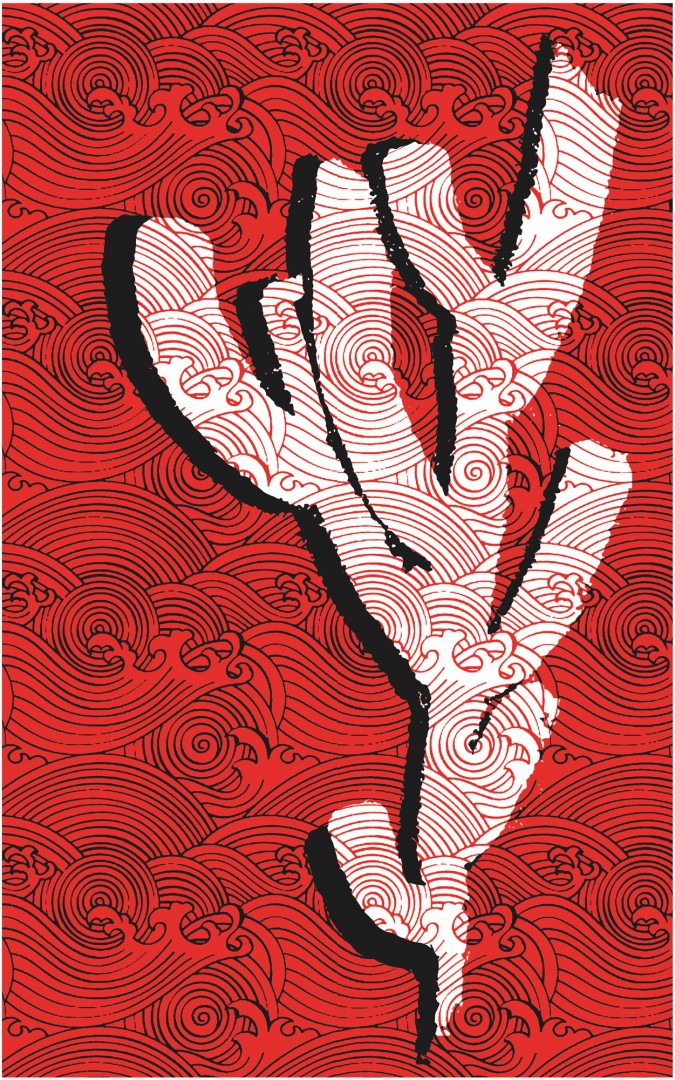

Look out too for Claire Drinkwater’s depiction of the bilaterally-symmetrical organism ‘Dickinsonia’, dark creatures on a rust-red background richly textured with filaments. “In spite of the clear impressions it leaves in the rock, the exact nature of this soft-bodied organism still provokes much discussion,” she explains. “I wanted to give the sense of this enigmatic outline embedded and preserved in sandstone.

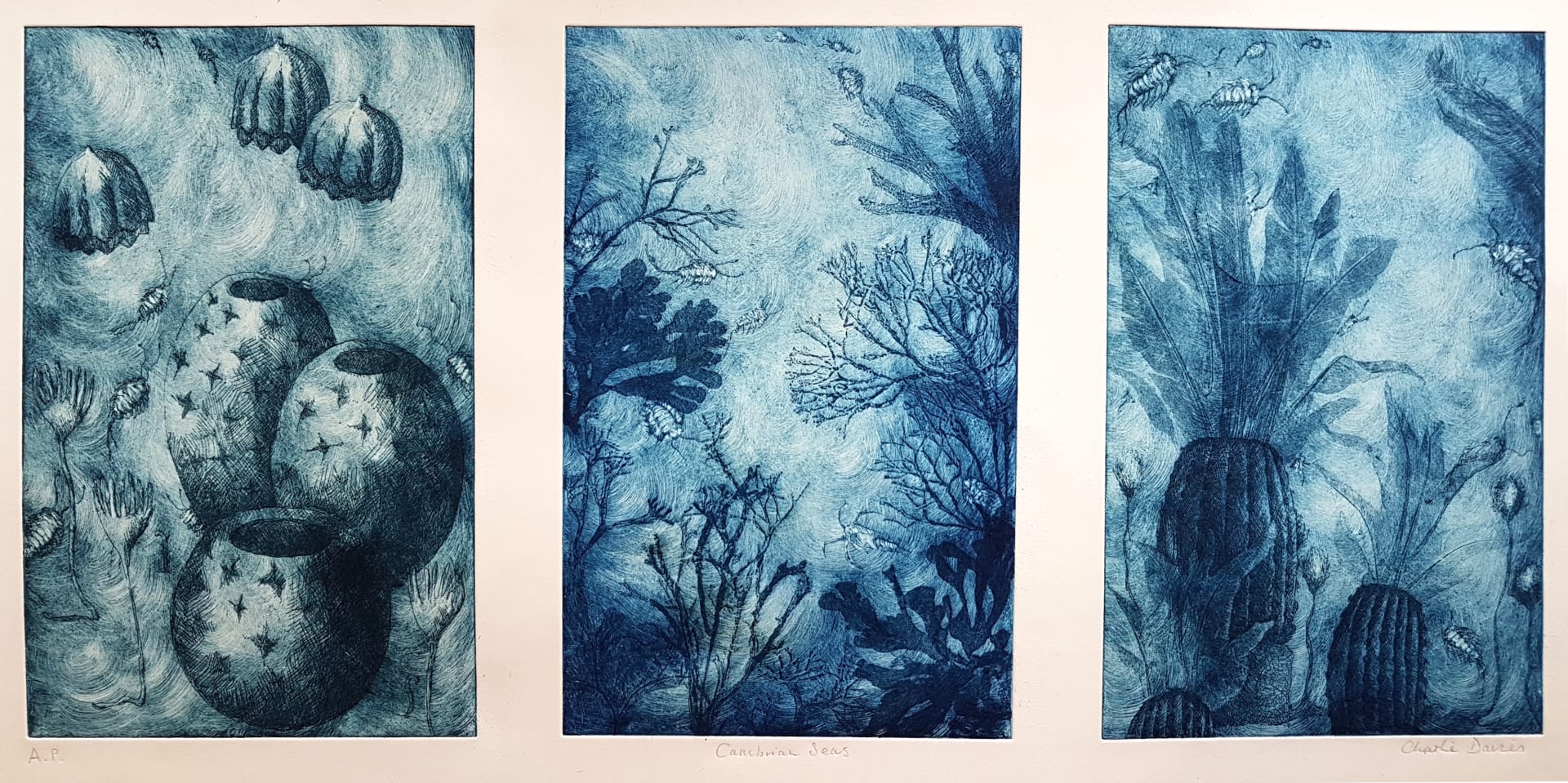

“Looking at fossils preserved in rock,” she continues, “it is easy to forget that early life forms all evolved in a marine environment.” Elsewhere in the exhibition she presents early animals against the blues of turbulent water and a triptych by Charlie Davies also evokes the mood of the underwater scenery of the Cambrian era and a real sense of the community of animals that inhabit it.

“I have spent the last few years of my printmaking practice working on soft-ground etchings where you take imprints from natural objects and use the impressions to make an etching plate. It seemed the perfect natural progression for me to use the same technique when inspired by these rare and beautiful early fossils,” Charlie says. “I began by using modern seaweed to create an image and then introduced underwater visitors.”

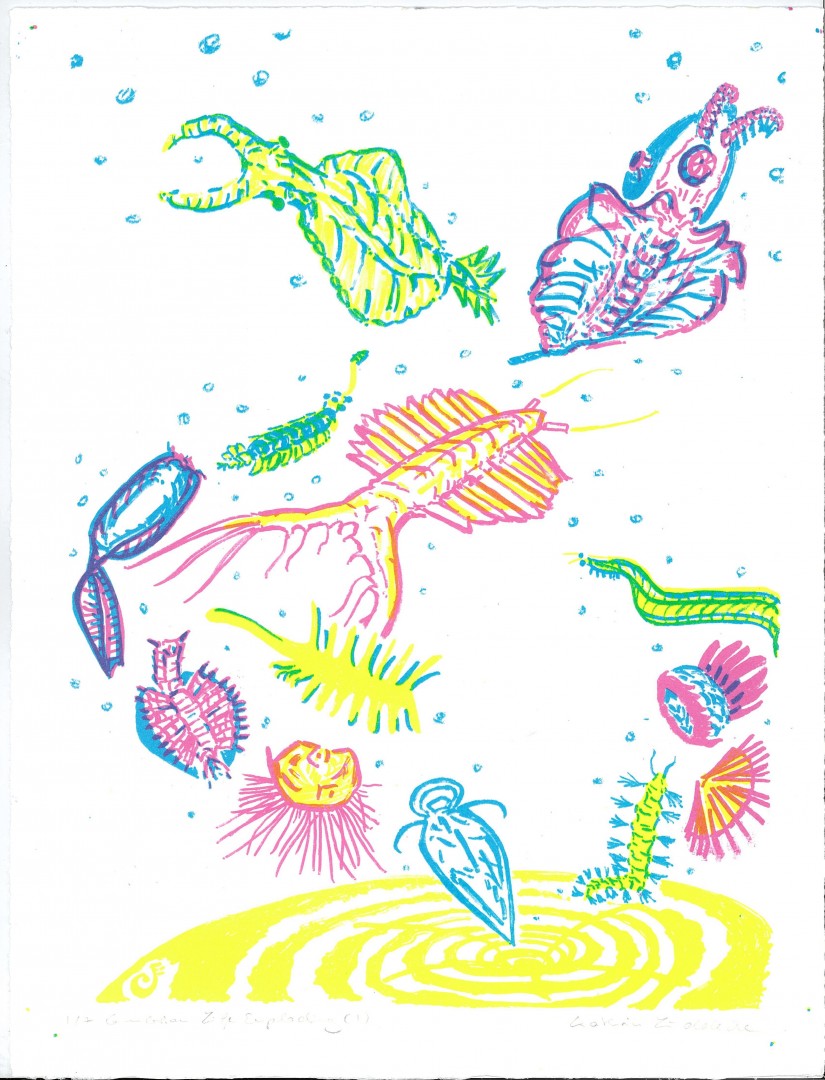

‘Cambrian Life Exploding’ by Kathrin Luddecke

The Cambrian explosion of early animal life appears in the landscape beneath our feet as a huge diversification in the shapes and permutations of animals and their body parts. This is depicted by Kathrin Luddecke in a wonderfully-cheerful screenprint. “I was most struck by the shorthand used of the ‘Cambrian Explosion’. The idea of all the various and wonderful forms we’ve been able to discover through their fossilised remains bursting out of the pre-Cambrian like underwater fireworks immediately came into my head.”

In equally bright and bold inks, printmaker John Stephens employs a Warhol-esque approach to a ‘walking cactus’, an underwater form similar to an insect about 7cm in length. His colour combinations catch the eye as he speculates that this organism hasn’t been seen for 500 million years.

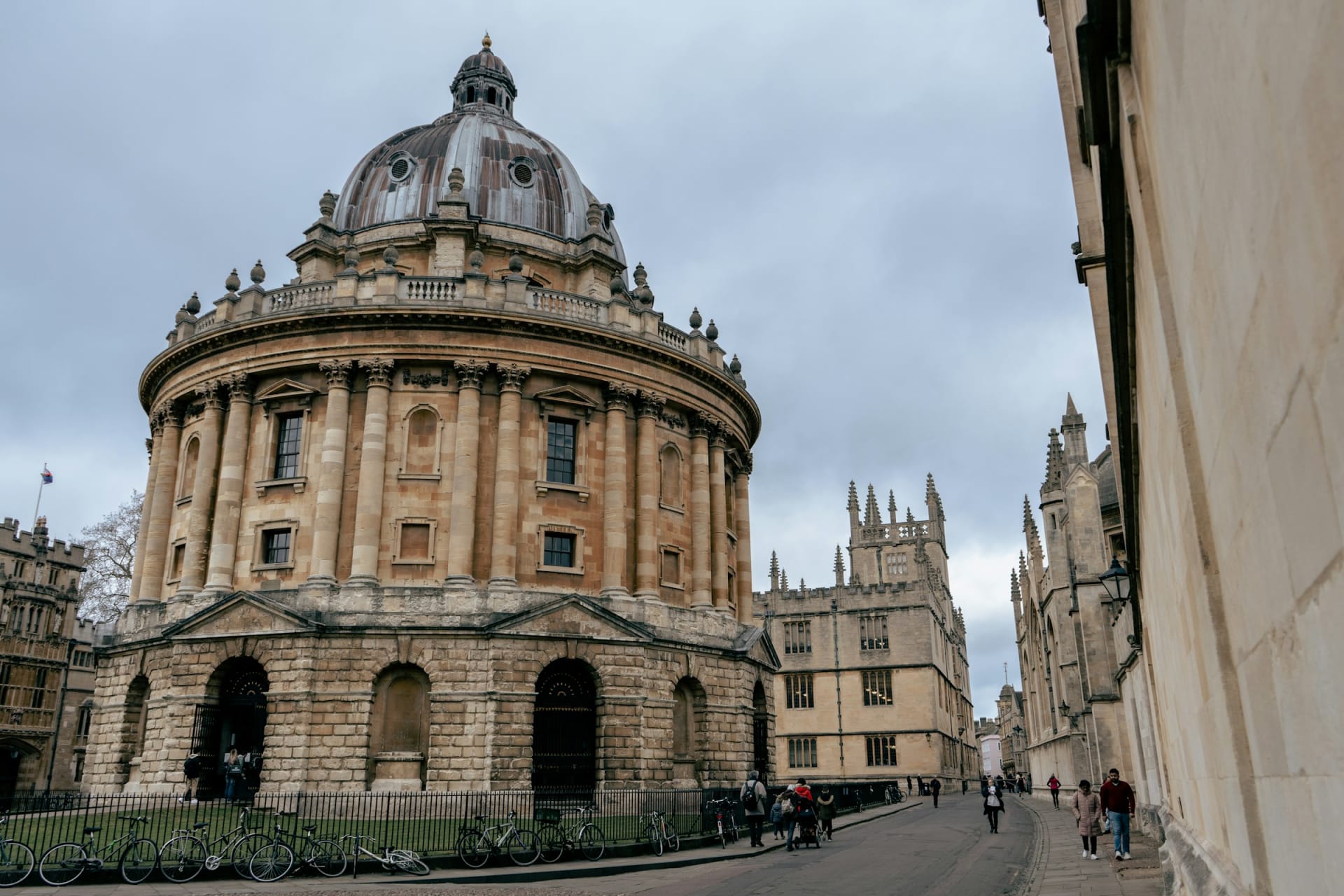

You can enjoy First Imprints and see a variety of printing processes including etching, aquatint, screenprinting and collography during IF Oxford, the Science and Ideas Festival. The exhibition is open on various dates between 19-28 October at the Oxford Printmakers’ workshop, Tyndale Road, Oxford. Visit if-oxford.com for times and further information on other festival events.

The Oxford Printmakers have also collaborated with Oxford University Museum of Natural History for First Animals which runs until February 2020.