We hear from Yatir Linden, a materials scientist and a pioneer of chocolate made without the high-sugar content of modern brands, and Aaron Torres, head roaster at Ue Coffee Roasters, a Witney-based company who handcraft specialist coffee to perfection, to discover the secrets of some of our favourite things to eat and drink.

Chocolate

Yatir Linden is a chocolate maker. Whereas a chocolatier takes readymade chocolate to create their designs, a chocolate maker builds the recipe and using a machine, grinds the ingredients themselves. This is the story of his Jericho-based micro-batch chocolate lab.

When I was in my early twenties I was involved in competitive endurance sport in which my performance really benefitted from a healthy lifestyle. I wished to eat well and even the chocolate in health shops contains 30-40% sugar. Butter, sugar and cream combined taste delicious but in large quantities aren’t necessarily good for you. Sugar for example is not only abundant, it’s addictive too. And although you can bake a cake from scratch at home and adapt the ingredients to make the end result healthier, it wasn’t really possible to make chocolate at home. And everyone loves a chocolate treat!

To make chocolate you first need to grind down the cacao beans or nibs (shards of cocoa beans), a process that takes at least a full day to grind the particles to a level of fineness that is imperceptible for one to notice. However, it has become possible over recent years because the automated machinery you need – unless you are going down the laborious pestle and mortar route – became smaller and more affordable. This stone-grinder which is the only option (at the moment) for small-scale chocolate making, was a revelation to me! From then, over five years I learnt to make chocolate from scratch, largely by trial and error.

To make chocolate you first need to grind down the cacao beans or nibs (shards of cocoa beans), a process that takes at least a full day to grind the particles to a level of fineness that is imperceptible for one to notice. However, it has become possible over recent years because the automated machinery you need – unless you are going down the laborious pestle and mortar route – became smaller and more affordable. This stone-grinder which is the only option (at the moment) for small-scale chocolate making, was a revelation to me! From then, over five years I learnt to make chocolate from scratch, largely by trial and error.

My wife and I began playing with the ingredients and in 2016 set up the Linden Chocolate Lab with the intention of more than halving the sugar content of chocolate and reducing the proportion of added sugar in the finished bar from the industry average of 30-50%. Even in 70% dark chocolate the average sugar content is usually 30%, and we have reduced this proportion in our chocolate to only 15-16%, even in white chocolate. It had never been done before.

Actually, when you reduce the sugar content, the natural flavour of the chocolate comes out more strongly, and now we combine the traditional batch-making methods of small artisan chocolatiers with the healthy ambition of the vegan and raw chocolate makers to create chocolate that is healthy and yet still tastes delicious.

We’re called the Linden Chocolate Lab because making good chocolate is a science – it’s a very meticulous, measured and precise process. Even as a child I was always interested in the structure of things and as a youngster I chose to study materials science as a kind of midpoint between chemistry and engineering, and everything I learnt applies to chocolate, from its crystalline structure to the way butterfat in the milk reduces the melting point of white chocolate – just as salt reduces the freezing point of water, as we know when preventing roads from becoming icy in winter. Chocolate’s also a polymorph, which means it can take on different crystal forms when it solidifies from liquid form.

We’re called the Linden Chocolate Lab because making good chocolate is a science – it’s a very meticulous, measured and precise process. Even as a child I was always interested in the structure of things and as a youngster I chose to study materials science as a kind of midpoint between chemistry and engineering, and everything I learnt applies to chocolate, from its crystalline structure to the way butterfat in the milk reduces the melting point of white chocolate – just as salt reduces the freezing point of water, as we know when preventing roads from becoming icy in winter. Chocolate’s also a polymorph, which means it can take on different crystal forms when it solidifies from liquid form.

I enjoy playing with flavours, and finding the perfect balance of spices is a real challenge. Our range includes both classic flavours like caramel and more unusual ones like pink peppercorn, which is sweet with a bit of kick. Some of our flavours such as chai masala and spiced coffee have multiple ingredients to get the taste just so, and I’m particularly proud of them as they’re hard to make.

You can join Yatir to hear more about chocolate making as part of IF Oxford, the science and ideas Festival (The surprising science of chocolate, Thursday 8 October).

____________________

Yatir is offering OX readers a 12% Linden Chocolate Lab discount, both online and in-store! Just use the code: OXMAG

_____________________

Coffee

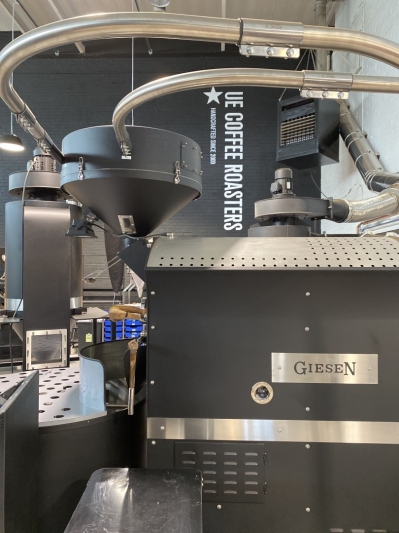

Aaron Torres, head roaster at Ue Coffee Roasters, grew up by a coffee expresso machine in Zaragoza, Spain, where his parents ran a café. Then having studied chemistry at university, he was keen to pull his two passions together. He trained to become a certified barista, before moving to Oxford in 2016 to both develop his language and put his roasting skills to good use for refined Oxfordshire palates.

A great cup of coffee is all about science. There are many chemical reactions throughout the whole process of roasting and brewing.

Of course, it all starts with the beans themselves, the seeds of coffee cherries, and even the soil in which the coffee plants are grown has an effect on the chemistry of the beans. We’ll roast each type of bean slightly differently to bring out the best taste. There are 100 different types of coffee bean but mostly only two of these are sold in supermarkets, Coffea arabica and Coffea robusta, and the prices of these are fixed globally. The other types are much more exclusive specialty coffees and that’s what we work with. There’s so much more variety!

We source our beans from all around the world, and it is important to us that the farms treat their staff properly, and schools are provided for the employees’ children, and so on, so that we are supporting the social development of these places.

We source our beans from all around the world, and it is important to us that the farms treat their staff properly, and schools are provided for the employees’ children, and so on, so that we are supporting the social development of these places.

Here in Witney we receive the raw agricultural material from these farms – green beans in jute sacks. The beans are 70% cellulose, a tough vegetable fibre that doesn’t dissolve, and first we roast the beans to break it down. It’s only then that we can release the flavour from the other 30% of the bean, a rich mix of sugars like fructose and glucose and acids, including citric acid. It’s the combination of these sugars and acids that makes coffee taste the way it does.

While roasting there is a Maillard reaction, when the sugars begin to caramelise, and that’s what gives coffee its sweetness. Even the timing of opening the roaster after the roasting process makes a difference because it alters the amount of carbon dioxide in the bean, which affects the flavour and texture. It is the carbon dioxide, for example, that gives an espresso its body, or crema; that rich, aromatic froth on the top of a shot of espresso.

While roasting there is a Maillard reaction, when the sugars begin to caramelise, and that’s what gives coffee its sweetness. Even the timing of opening the roaster after the roasting process makes a difference because it alters the amount of carbon dioxide in the bean, which affects the flavour and texture. It is the carbon dioxide, for example, that gives an espresso its body, or crema; that rich, aromatic froth on the top of a shot of espresso.

Then during the brewing process, we extract the sweetest part of the coffee. As with any chemical reaction, it is by measuring all the variables precisely – from the quantity of dried coffee and the amount of water, to the temperature of the water and the length of time it is brewed – that we achieve the sweetest and most balanced flavour in every cup. Under-extraction will make the finished drink rather sour, and extracting too much flavour makes the coffee bitter. And so, we find that perfect balance for a delicious coffee. We always use filtered water as a cup of coffee is 98% water after all, so the chemistry of the water will alter the coffee too.

We have three machines at Ue Coffee Roasters – the smallest of which roasts just 100g of green beans at a time. I enjoy experimenting with the different variables to work out how to get the best tasting coffee from each type of bean. South American beans tend to be mild with a chocolatey-sweet taste; African coffee has a complex and lively flavour with more fruity and floral aromas; whilst Asian varieties have spicy notes of cloves or tobacco, nuts or pepper.

You can hear more about the science of coffee, from the cultivation and harvesting of the coffee beans, through the selection and roasting processes, to the grinding, brewing and tasting experience in a digital event as part of IF Oxford, the science and ideas Festival (The art and science of coffee, Saturday 3 October).