There are some figures – cultural icons – who seem to occupy such a different reality that the idea of them being as human as the rest of us seems surprising. For several heady years, Penelope Tree defined the free spirit of the 60s, endlessly portrayed through a photographer’s lens, inevitably that of her lover, David Bailey.

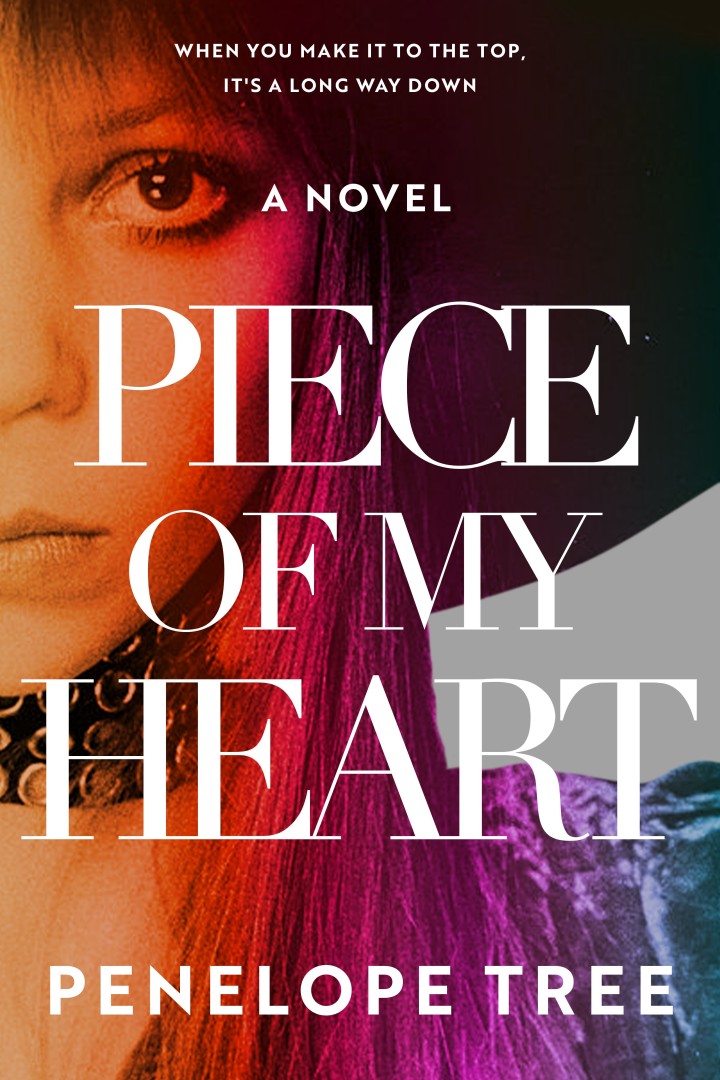

Feted for her distinctive look, her beauty was described as ‘alien-like’ in its otherworldliness, but it was more than her wide-side eyes or endless limbs which set her apart: it was her cultural impact. I met up with her in London to discuss her recently released novel, A Piece of My Heart, slightly concerned as to how I might establish rapport with someone I could only see as an archetype. I shouldn’t have worried. I planned with time to spare so that I’d could gather my thoughts in the posh hotel lobby before meeting her but she, too, was early. Instantly recognisable (beautifully dressed, tall and yes, striking) I went over to say hello and was straightway reassured by the warmth and compassion in her penetrating brown eyes and the calm, light precision with which she speaks.

1967 Penelope Tree © David Bailey

Her patrician beauty was first captured by Diane Arbus at age 13 but the prospect of a modelling career was vetoed by her father. Four years later at Truman Capote’s Black and White Ball, her slashed tunic dress caused a sensation by creating a fashion moment and her father relented. Encouraged by Vogue editor Diana Vreeland, she worked with Cecil Beaton and Richard Avedon before moving into David Bailey’s Primrose Hill flat as his muse and lover. There followed a dazzling career few years but ultimately, “the flame that burns twice as bright burns half as long” (Laozi). Late onset acne led to scarring which ended her career, or at least put it on pause. In the 2000s she returned to the runway and has worked for a number of labels since; Burberry, Fendi, Valentino.

During the intervening years she has lived largely out of the spotlight. There have been two subsequent significant relationships, and she is mother to two children. She has become known for her charity work, most considerably as Patron of Cambodian-based Lotus Outreach which works with local grassroots women’s organisations. She struck me as a person who looks forward, not backwards and yet we were together to discuss A Piece of My Heart which set in the late 60s/early 70s. The story is instantly recognisable to those familiar with Tree’s own; the main protagonist is a young girl, Ari, who lives within the upper echelons of British society and is catapulted to fame after being championed by Diana Vreeland. After meeting charismatic British photographer Ramsey she moves into his Primrose Hill flat, and their tumultuous relationship is played out in public view.

Why now? I ask. “In my early 60s my relationship broke up. I moved to the country where I was living on my own. There were no more excuses; I knew there was a book about that time, and I wanted to make sense of it for myself. I know people like books where the protagonist loses everything” – riches to rags, I suggest – “Yes, I had lost what I gained, and it took some time to get over the pain of that, but through the pain I became my own person with my own values”.

Ari’s story obviously mirrors Tree’s own, but it is compressed. A Piece of My Heart is a fully immersive read which stands in its own right as a page-turner even if you’re unfamiliar with the legends and myths surrounding Bailey and Tree. Without wanting to spoil the end, it did strike me that this was the point at which ‘Ari’ diverged from Penelope. “Writing allows you to compress timelines, so the protagonist works things out quickly whereas in reality it takes ten years of therapy – or whatever. I wanted to write [my story] as fiction to allow that to happen.”

One thing I’ve reflected on in the various interviews I’ve conducted is how much of art is autobiographical, from a piece of literature to a painting or even a song. I’m always fascinated by how it must feel to create a piece which comes from a place which is so deeply personal and see it mutate as it takes on its own significance once it becomes public property. “Correcting proofs changes your attitude to what you’ve written, it becomes a job and once it goes off to the printer it’s not yours. I won’t read it, not yet, not for a couple of years.” And what does your family think, have they read it? “My family…like it. My children read a lot of novels and I think they’re proud. They always say ‘but you’ve never told us any stories’ at which point we both roll our eyes, and laugh at the fact that when your children are young, the idea of their parent having had a life is unimaginable, even when your mother is a bone fide icon.

And so age equals wisdom? “As you get older you see things in cycles, and it gives you a sense of peace.” Is that happiness, I wonder aloud, and there follows quite the philosophical discussion about how our concept of the ideal changes as we grow: “Back then it was hedonism rather than happiness; driving around in a car with no roof, seeking extreme experiences of life and fun.” I suggest that contentment is massively underrated or seen as settling but perhaps it is the secret to a happy life, but she disagrees: “You always have to keep aspiring to be in the present, it’s the biggest healer I’ve found. Whatever you’re going through, if you’re present and you sit with it and experience it, it moves on faster. That’s the skeleton key to being happy, or present; being in the moment”.

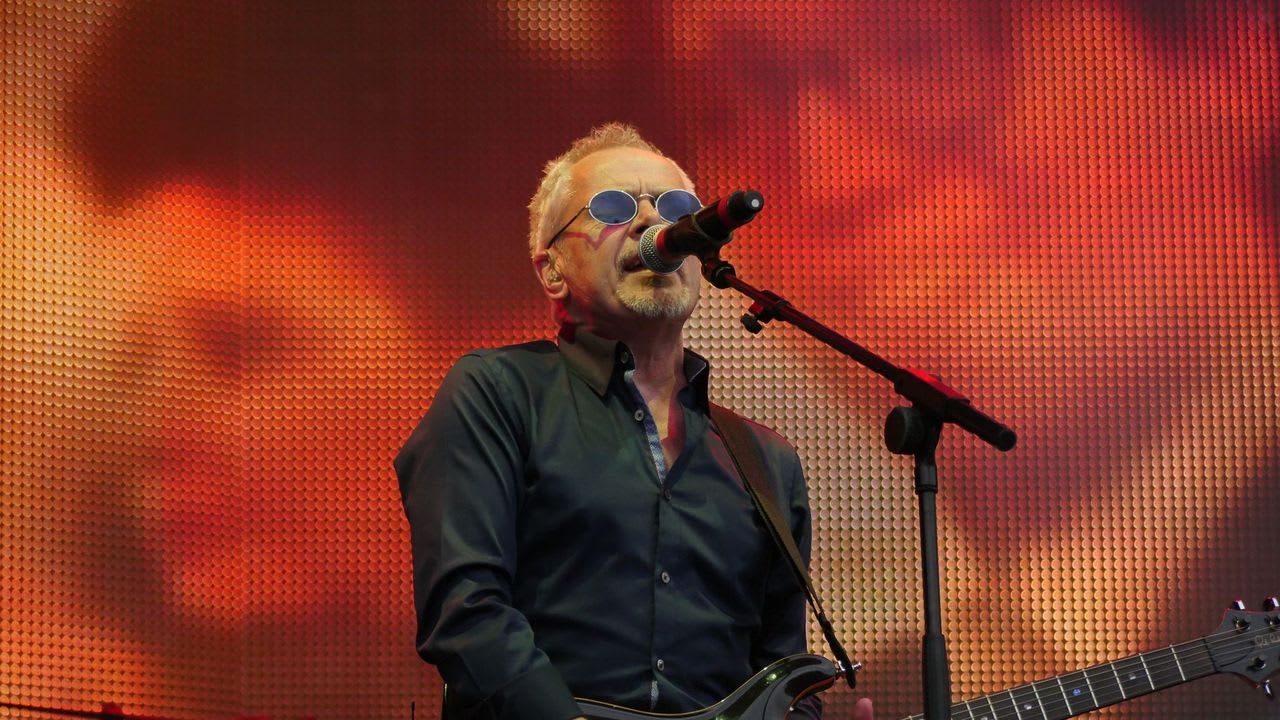

© Fenton Bailey

What is so striking in A Piece of My Heart is how Ari determinedly seeks out counterculture. Although her family come from a place of privilege once Ari strikes out on her own she finds her place with Australian ex-pats living together in a London flat. Moreover, as the novel progresses, Ari is increastingly drawn to Eastern philosophy and what has come to be broadly termed, a hippy lifestyle. Was this another instance of art imitating life?

“Hippies stood for all the good things, like racial equality. I was wanting to be something; I can’t say I was free and peace, and all that hippies represent.” And the Aussies? “I got to know the Aussies in the 60s. Everyone knew everyone. Around Chelsea, Kensington, even Knightsbridge, you just ran into each other.” Her crowd as depicted in the book are clearly identifiable as founders of the ultimate counterculture magazine, Oz, and Cindy, who styles Ari’s early shoots? She’s based on the fashion pioneer, Jenny Kee “still a very big deal and a buddy”.

1970 Penelope Tree & The Wigwam © David Bailey

In addition to peace and love, the 60s are also notable for the emergence of female voices and it was at this time that the second wave of the feminist movement started gaining momentum. Was this something that impacted on her? “Back then it was not the sisterhood…other women were no-go areas. I had girlfriends, but mostly my hackles were raised when they threw themselves at Bailey”.

That said, one thing I had been fascinated about her prior to our meeting is the extent to which she has been defined by the men of the era. Search her up online and you’ll read what Bailey, John Lennon and Richard Avedon all said Penelope Tree and yet, it seems that it was the women who ultimately supported her. “It’s a good observation. I had four female mentors I couldn’t have done without. They helped me do so much. Other than Diana Vreeland none were in fashion, but each was inspiring. However, I had to learn to look at life through my own lens.”

Which is exactly what she is now doing. Literally.

A Piece of My Heart (Moonflower May 2024) is out now in Hardback and Kindle formats.