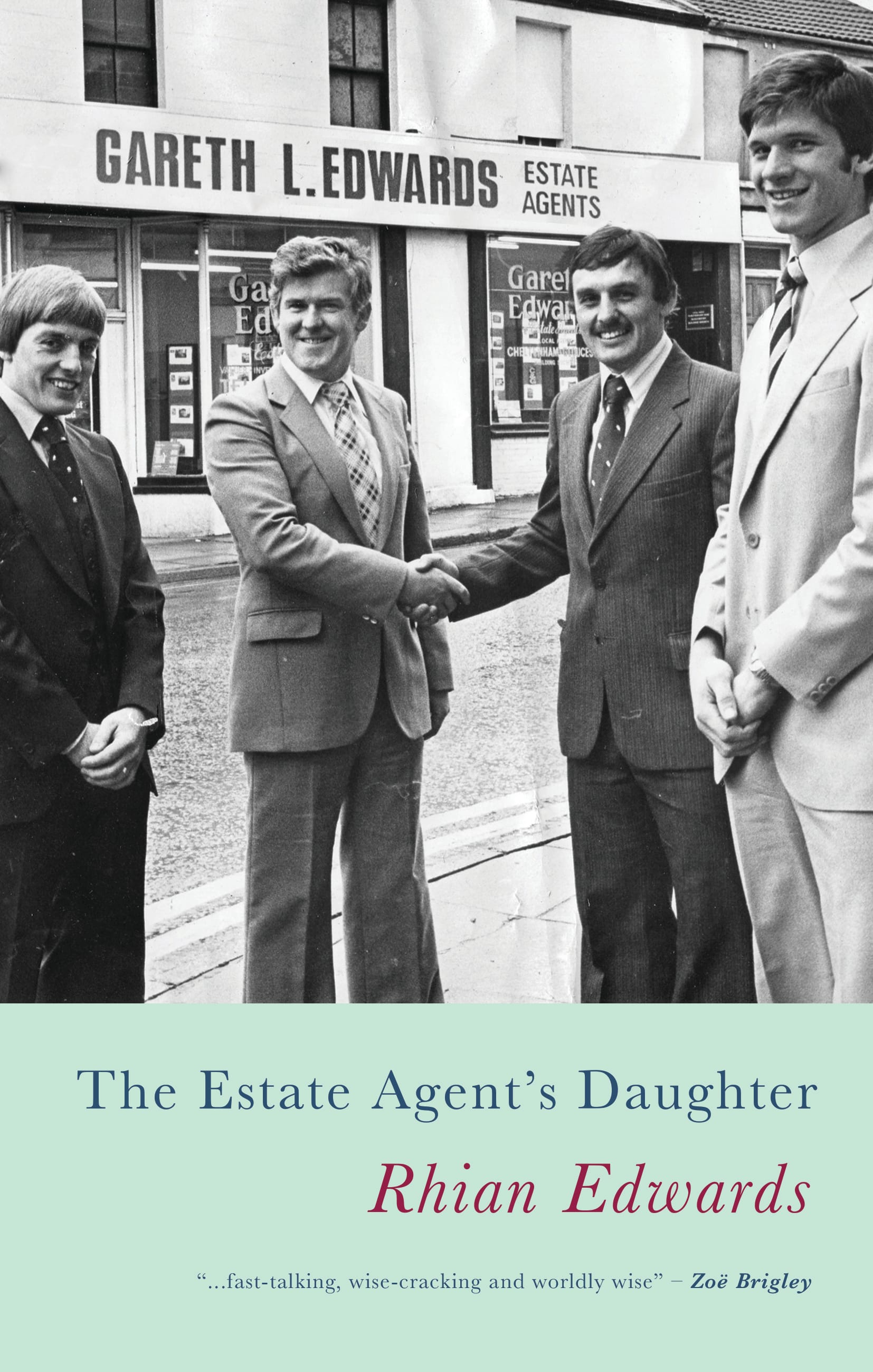

We speak to Welsh poet, Rhian Edwards following the virtual launch event of her new poetry collection The Estate Agent’s Daughter, the eagerly anticipated follow-up from her award-winning, Clueless Dogs.  We discuss the ways in which lockdown has impacted her writing while touching upon her new work and her journey towards becoming the writer she is today.

We discuss the ways in which lockdown has impacted her writing while touching upon her new work and her journey towards becoming the writer she is today.

How was your virtual launch event in June?

It was somewhat surreal. It was the first time I had ever used Zoom, so the audience appeared like silent hostages. But it was good to unleash the new material.

Has lockdown given you more time to write, or have you found yourself preoccupied with other things?

Strangely enough, I found I had less time to write. I find it hard to write when I have my daughter in the house. I also blame homeschooling – by the time we had got through the day’s syllabus, we were always smack bang into dinner and bed routine and I’m usually asleep before my daughter is. I need to train myself to be one of those 5.30am risers who does her yoga, meditation, gratification journal and poetry before her daughter rises. But I don’t know if this is all part and parcel of my procrastinatory and evasive attitude towards writing.

You started your writing as a singer/songwriter, why did you make the move from this area?

I never felt I had ‘permission’ to write poetry until I visited the Poetry Café in London in my twenties and met a bunch of poets in Soho that had just come back from the longest-running open mic in the UK. I was fascinated that such a scene existed, that there were willing performers and even more surprisingly a willing audience. They invited me to come along the following week and so I did. The terrible admission is, I was surprised by how much bad writing people were confident to perform. Although I didn’t know much about poetry, I knew what bad writing looked and sounded like. My career in poetry was forged from total  arrogance. I thought, ‘I can write better than some of this’. I wrote one poem, which was meant to be my first and last. I performed it at the open mic at the Poetry Café in January 2003 and was absolutely buzzing afterwards. Niall O’Sullivan and James Byrne approached me immediately and asked if I would like to do a feature-length set at their night Young Blood in the February. And so, I had to come up with 15 minutes more material. That’s how I regarded poetry at the time. I then bought a pocket diary and listed every single open mic night in London. I made a CD and sent it off to Apples and Snakes and Express Excess. I had the bug. One Sunday, I read at four different poetry events. Also, on a completely parsimonious note, there was more money in poetry gigs than music gigs at the time.

arrogance. I thought, ‘I can write better than some of this’. I wrote one poem, which was meant to be my first and last. I performed it at the open mic at the Poetry Café in January 2003 and was absolutely buzzing afterwards. Niall O’Sullivan and James Byrne approached me immediately and asked if I would like to do a feature-length set at their night Young Blood in the February. And so, I had to come up with 15 minutes more material. That’s how I regarded poetry at the time. I then bought a pocket diary and listed every single open mic night in London. I made a CD and sent it off to Apples and Snakes and Express Excess. I had the bug. One Sunday, I read at four different poetry events. Also, on a completely parsimonious note, there was more money in poetry gigs than music gigs at the time.

What are the main differences between these two forms?

My lyrics are far simpler than my poems – they have to be. My poetry is quite dense, but so long as you’re just reading it or just listening to it, you stand a chance of deriving the meaning and sense. With music, there’s far too much going on, you have the melody, the timbre of the voice and then the lyrics. That’s the order in which I listen to songs. To have complicated lyrics thrown in as well, I fear may estrange the audience somewhat.

When you were growing up, do you recall having any poetry or poets who inspired you?

I remember listening to Under Milk Wood ad nauseam as a child and rather loving the musicality and richness of the language and even the humour, not to mention Richard Burton doing the narration. I know I’m torturing a cliché to be another Welsh poet inspired by Dylan Thomas, but that was the acceptable poet that was allowed into the house during your childhood. School pretty much squeezed the joy out of poetry and reduced it to a science of line breaks, alliteration and assonance. I was once read an article in the Huffington Post where a poet failed an exam on her own poem, which pretty much confirms much of my feeling towards the way poetry is taught in schools. However, I did love Ozymandias by Percy Shelley. I remember that was one poem that really resonated with me, which I stuck in my special box where I kept my cheeky pack of menthol cigarettes and my few adolescent love letters.

Do you think there’s a conflict between the page and performance poetry worlds?

There is a conflict, but I think the Berlin Wall is coming down on that one. Picador have recognised the value in publishing performance poets like Kate Tempest, John Cooper Clark and Hollie McNish and I’m sure sales figures have soared as a result. Penned in the Margins and the late Ugly Little Press also recognised the value in publishing performance poets. By the same token, many performance poets transcend both the stage and page and the poetry wholeheartedly warrants its presence in print. One of the original Faber poets who combines stage and page is Hugo Williams, a hugely charismatic stage presence with collections that have won him the T.S.Eliot prize, the Queen’s Medal for Poetry. Not to mention, Dylan Thomas and his evangelical style of reading his poetry. Similarly, the change is happening in the opposite direction. You’re finding page poets like Caroline Bird and Helen Mort both recognise the value of learning their poems off by heart to truly engage an audience. Page poets are starting to invest the effort in learning their poems by rote, rather than staying safely behind the fourth wall of their paperback, like it’s some kind of forcefield against a discerning audience.

You’ve spoken before about the importance of someone’s hometown and how the relationship they can have with it shapes them as a person, in which of your poems would you say this is most prevalent?

Counting Boards, Bridgend, Return of the Native, Alison, Free, No Obligation. The truth is I was at my happiest and safest when I lived in Bridgend and I would always come back here if I was unhappy or broken, recharge and then return to my unhappy or broken life in Derbyshire or London. I’m a small-town girl, I always have been and always will be. I tried to be something else, especially when I settled in London. I always felt somewhat out of my depth, over compensated and suffered from tremendous impostor syndrome, which I still do, to a tremendous extent. When returning to Bridgend I feared I would be recognised solely as my father’s daughter and constantly be judged according to that status, however it enabled me to live more like an adult, to enjoy a slower pace of living, a five-minute commute to work.

This collection in particular touches on some very personal topics, do you find it cathartic to express your feelings into poetry, or do you ever feel vulnerable when coming to publish something so personal?

While I appreciate poetry can be a form of therapy for people, it is the act of writing and shaping a poem that is therapy, regardless of what it is about. It energises me in a way that only performing a poem on stage does, (which I truly miss in this ‘new normal’). It’s about the beauty and the music of the words being strung together or even making an ugly topic beautiful. There are certain subjects in my life I avoid entirely that I don’t wish to discuss in tremendous detail, particularly the details of the domestic violence that occurred during my mercifully short marriage and intimate and intricate details about my daughter. I’m mindful that one day my daughter will read these poems and I’m wary of making her or her father a central theme. Melissa Lee Houghton once said, “You’re innocent. And my poems aren’t innocent”. I don’t feel vulnerable – it’s what I do. I don’t mind laying myself naked on the page, because I don’t take myself all that seriously and recognise the ridiculousness of myself. In fact, I think it’s the self deprecation of my poetry that resonates with people. It makes me and my poetry more human.

Do you have any favourite writers at the moment?

I love poets with a sense of humour, who combine tragedy with an innocent, infantile lens. Hugo Williams is a consummate favourite of mine. I was recently introduced to Tony Hoagland, who I absolutely adore. I love Joe Dunthorne too. Emily Cotterill is one to look out for. I call her the Shane Meadows of poetry. She has an idiosyncratic Midlands vernacular in her work that gives her a fully fledged and unique poetic voice, which defies all the rules.

What’s next for you?

I’m taking a new collection sabbatical, I’m ‘resting’ or avoiding the laptop again. Hopefully when my daughter resumes school, I can buckle down again on my day off. I’m even planning on putting my daughter in a one-hour arts club after school on a Thursday, just so I can have that one-hour to write in a coffee shop. I’ve got a working title for the third collection, which is Out of the Will. This feels like a natural successor to the Estate Agent’s Daughter, given that it is a constant threat made by the eponymous Estate Agent.

Rhian Edwards’ newest collection, The Estate Agent’s Daughter is now available.