As part of IF Oxford, on Sunday 9 October step away from the hustle and bustle of Oxford’s High Street into the tranquillity of the Oxford Botanic Garden, which is celebrating its 400th anniversary this year. Here, visitors will discover that plants, often the unsung heroes of the world, underpin many of our hopes for a cleaner planet and a better future.

Plants for the Future, a family-friendly event, has several activities running throughout the day, where visitors can learn about some of the astonishing ways plants can shape our future.

“Children love to plant seeds and are amazed by the enormous sunflower that will emerge, but don’t always think about the other ways plants can inspire us – plant science is so much more than identifying, growing and surveying plants,” explains Lauren Baker, Education Officer at the Oxford Botanic Garden, “and during the Festival we’re going to share some of their hidden wonders and what they can teach us.”

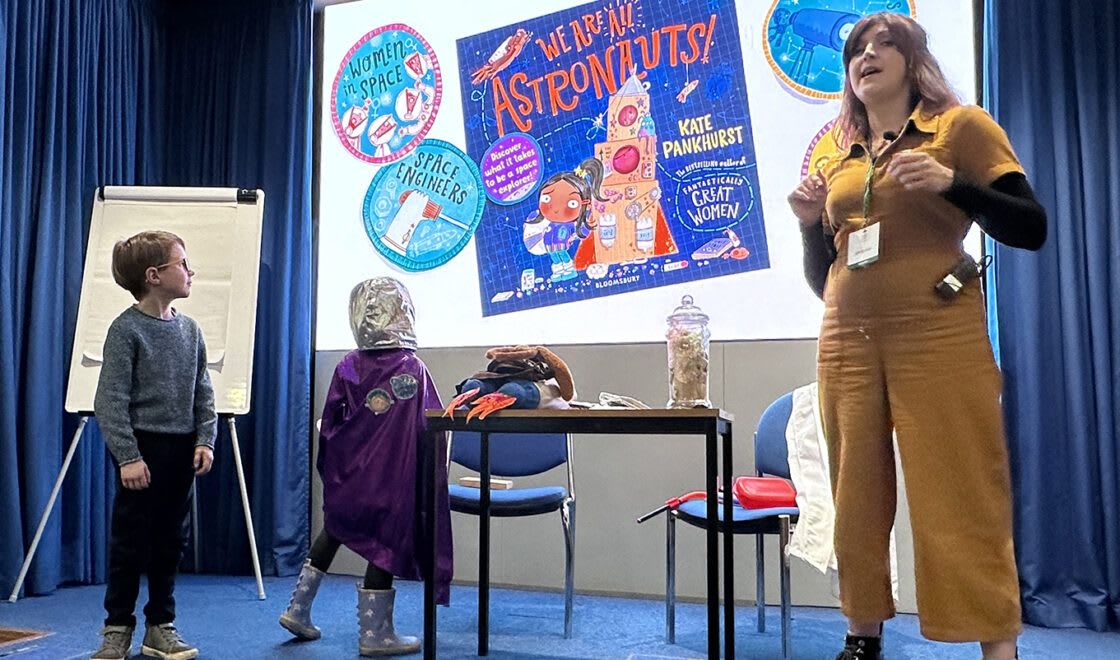

Did you know, for example, that humans are never going to venture further into space successfully without mastering the challenges of what we can eat when we’re there? If you were to carry the amount of fresh food needed for a year’s exploration on Mars (which has very toxic soil), the fuel requirement alone to get the spaceship off the surface of Earth makes such a trip currently unviable. That’s why astronauts make do with a lot of freeze-dried and vacuum-packed food, as it’s lighter and easy to store (although apparently not very tasty). For longer term space travel, astronauts need to be able to grow their food out in space, so around 80% of the experiments that are happening on the International Space Station today involve plants.”

Did you know, for example, that humans are never going to venture further into space successfully without mastering the challenges of what we can eat when we’re there? If you were to carry the amount of fresh food needed for a year’s exploration on Mars (which has very toxic soil), the fuel requirement alone to get the spaceship off the surface of Earth makes such a trip currently unviable. That’s why astronauts make do with a lot of freeze-dried and vacuum-packed food, as it’s lighter and easy to store (although apparently not very tasty). For longer term space travel, astronauts need to be able to grow their food out in space, so around 80% of the experiments that are happening on the International Space Station today involve plants.”

In the 2015 film Martian (directed by Ridley Scott), Matt Damon plays a solitary astronaut trying to grow enough potatoes to stay alive on Mars. “It’s highly unlikely NASA would have allowed him to take potatoes in the first place,” laughs Lauren. “He’d have been much more likely to have taken rocket and tomato seeds, maybe a nice bit of beetroot. The science of growing food in confined spaces, like on the ISS and in vertical farms which are usually indoors with crops grown in stacked layers, is equally useful on Earth to maximise growth in a restricted footprint and to increase food productivity.

By studying the plants in the Botanic Garden and elsewhere around the world, scientists are also learning useful lessons for engineering on both micro- and macro-levels.

“Photosynthetic organisms have been around for 2.4 billon years: that’s more than half of the Earth’s lifespan and more than a billion years before the earliest animals. Humans’ time here is a mere blink of an eye as far as the Earth is concerned” continues Lauren. “Because they’ve had so much longer to overcome numerous environmental challenges, it shouldn’t surprise us that plants hold the solutions to many of the challenges we still face; we just need to take the time to look.”

Dr Chris Thorogood, Deputy Director and Head of Science at Oxford Botanic Garden and Arboretum, studies parasitic and carnivorous plants including the Nepenthes pitcher plants; tropical carnivorous species with dangling pitcher-shaped flowers. “It’s a group that’s very diverse: for those people who are aware of how Darwin noted that finches in the Galapagos Islands with different shaped beaks evolved for different purposes, they’re the plant equivalent. Some digest insects, others have evolved to digest leaf-litter (“the ‘vegetarians’ of the family”) and another is nicknamed the ‘toilet’ pitcher plant because it has a very sweet sugary substance on its ‘lid’. Shrews lap up this sap which includes a rapid-acting laxative, and the plant then gets its nitrogen for free from the shrew’s faeces which it expels there and then. Other varieties encourage small bats to rest in them and get nutrients from their guano [excrement].”

Dr Chris Thorogood, Deputy Director and Head of Science at Oxford Botanic Garden and Arboretum, studies parasitic and carnivorous plants including the Nepenthes pitcher plants; tropical carnivorous species with dangling pitcher-shaped flowers. “It’s a group that’s very diverse: for those people who are aware of how Darwin noted that finches in the Galapagos Islands with different shaped beaks evolved for different purposes, they’re the plant equivalent. Some digest insects, others have evolved to digest leaf-litter (“the ‘vegetarians’ of the family”) and another is nicknamed the ‘toilet’ pitcher plant because it has a very sweet sugary substance on its ‘lid’. Shrews lap up this sap which includes a rapid-acting laxative, and the plant then gets its nitrogen for free from the shrew’s faeces which it expels there and then. Other varieties encourage small bats to rest in them and get nutrients from their guano [excrement].”

The rim of this plant, the peristome, although ridged and rough when stroked in one direction, is exceptionally smooth when stroked in the other. This super-hydrophilic surface is usually wet, because the species grows in the rainforest, and it is the most slippery natural surface ever discovered. It’s great for the plant because insects can’t help but aquaplane and slide into the plant’s ‘stomach’. It’s great for materials science, too, because engineers have looked at the structure in microscopic detail and see parallel lines even at a cellular level. By recreating this surface to mimic its structure, engineers found they could control the flow of minute water droplets very precisely and this has nanotechnology applications for inkjet printers and antifog glasses, lenses, and windows.”

Elsewhere in the engineer’s toolkit, other plants that can be seen in the Botanic Garden have provided the inspiration for colossal building projects. The Amazonian waterlilies can grow up to six feet in diameter, with ribs radiating from the centre, enabling them to support incredible weight compared to their relatively very thin structures. These were the inspiration for the Crystal Palace built to house the 1851 Great Exhibition – an elegant and economical design in glass with transverse and longitudinal iron girders modelled on the waterlily leaf.

Elsewhere in the engineer’s toolkit, other plants that can be seen in the Botanic Garden have provided the inspiration for colossal building projects. The Amazonian waterlilies can grow up to six feet in diameter, with ribs radiating from the centre, enabling them to support incredible weight compared to their relatively very thin structures. These were the inspiration for the Crystal Palace built to house the 1851 Great Exhibition – an elegant and economical design in glass with transverse and longitudinal iron girders modelled on the waterlily leaf.

“This kind of thinking can be applied to many buildings,” comments Lauren, because the global cement industry represents 8% of all carbon dioxide emissions: “If engineers used plant structures as inspiration when designing multistorey carparks, for example, there could be substantial space increase inside whilst cutting down on the amount of concrete required, – and even a 10% reduction would have a real impact on its carbon footprint.”

Plants are also the inspirational backbone of Singapore’s garden city; an initiative to use sustainable designs for the built environment. The entire city is transformed into a botanic wonderland as plants flourish from the ground to the tops of buildings: a green model that reduces the city’s negative environmental impact. “Amazing things happen when you marry design and science,” Lauren adds.

“Singapore’s garden city is a showcase of incredible building designs which use plants creatively. Architecturally, structures are engineered to consider the needs of the plants – for example, providing enough space for the roots of trees – and also to support the huge weight of the biomass, both as it grows and when it rains (as the plants and soil soak up the water). Not only does planting reduce carbon dioxide emissions; it also keeps the ambient temperature from rising within buildings.

“Singapore’s garden city is a showcase of incredible building designs which use plants creatively. Architecturally, structures are engineered to consider the needs of the plants – for example, providing enough space for the roots of trees – and also to support the huge weight of the biomass, both as it grows and when it rains (as the plants and soil soak up the water). Not only does planting reduce carbon dioxide emissions; it also keeps the ambient temperature from rising within buildings.

As part of the IF Oxford event, visitors will be able to see the Merton Borders – an innovative planting scheme exploring climate change and rising global temperatures in urban planting. Designed by Professor James Hitchmough from the University of Sheffield, and using plant species from the central plains of America, southern Europe and South Africa, the Merton Borders are nearly 1,000 square metres of landscape planted to illustrate what the UK plants would be like if the British climate continues to become drier and drier with monsoon-like episodes of occasional heavy rain. These beds are both naturalistic and ornamental, a dramatic immersive section of the garden. Here, the striking flowering spikes of giant fennel tower over grasses that waft in the wind to recreate the feeling of being in a South African fynbos (fine bush) shrubland habitat. It’s a world apart from the herbaceous borders which are home to traditionally popular garden plants which need watering twice or even three times a day in the height of summer. Blooming beautifully with far lower water requirements, the Merton Borders show us what we can all do to make our gardens more sustainable from a water-use perspective.

“We’ll be exploring sustainable fashion, too, during IF Oxford,” continues Lauren. “The Chelsea Flower Show included its first textile garden this year which was exciting to see: everything in it could be used as a fibre, a dye or as part of a cloth-making process, and it’s being relocated to Oxford, to Headington School for their textile students to use. Meanwhile, at the Botanic Garden, we have numerous plants essential for the textile world, such as indigo and turmeric which are traditionally used as dyes, and there’ll be some surprises, too, as we encourage people of all ages to rethink damaging fast fashion habits.”

Plants for the future, Oxford Botanic Garden, Sunday 9 October, 10.30am – 3.30pm