Customs and traditions are often things we accept without question. Why do we put candles on a birthday cake? Why is it called a honeymoon? What exactly is mistletoe?

Bonfire night is a bit different. The tale of Guy Fawkes and the Gunpowder Plot is fairly ubiquitous, and even has its own nursery rhyme enjoining us to ‘Remember, remember the fifth of November...’ From a fairly young age we know that the plotters wanted to blow up Parliament and their failure to do so was celebrated each year thereafter by burning effigies of Guy Fawkes. But who were the plotters, why were they trying to blow up Parliament, and how has the tradition lasted nearly 420 years?

Sectarian Origins

To understand what Guy Fawkes was up to in 1605 we need to scroll back to Henry VIII. After taking control of the English church in the 1530s, a period of religious tension ensued between Protestants and increasingly marginalised Catholics. When Elizabeth I took the throne, an uneasy compromise was established that required any public officer to swear allegiance to the monarch as the head of the Church and state. Indeed, it is thought that it was this settlement that prevented the leader of the Gunpowder Plot, Robert Catesby, from taking his degree from Oxford.

Famously unmarried, childless and unwilling to nominate an heir, Elizabeth I left a vacuum in which the simmering religious resentments of previous decades percolated with the politics of royal succession. Eventually, after negotiations led by Robert Cecil brought James I to the throne, the future of the monarchy was deemed secure, and the sectarian hostilities were quelled. At least to begin with, James appeared to be more moderate in his view towards Catholics, preferring quiet tolerance over overt persecution.

However, across Europe wars of religion were raging between Protestants and Catholics – a feature of which was the attempt to assassinate Protestant rulers. The removal of Kings was given a scholarly foundation in 1599 by On Kings and the Education of Kings by the Jesuit priest Juan de Mariana. He argued that there was a legal right to remove a tyrannical leader – so-called ‘tyrannicide’.

Plots

Before Fawkes and Catesby, others hatched plans to remove James from the throne and install a Catholic replacement. Two Jesuit priests planned the Bye Plot to kidnap the King and hold him hostage in the Tower of London to extract concessions. Concurrently, in the so-called Main Plot, a handful of Lords including Walter Raleigh, hoped to remove James and replace him with his cousin Arbella Stuart. Both plots failed and all conspirators were arrested. The two priests were executed along with George Brooke, an aristocrat connected to both schemes but James pardoned the rest of the schemers, again preferring mercy over punishment.

Despite this, the environment for Catholics was growing more hostile year on year. In 1604, having discovered his wife had been sent a rosary from the Pope, James denounced the Catholic Church and restarted the collection of fines from recusant Catholics. In his speech at the opening of parliament in 1604, he clearly established his desire not to allow Catholicism to proliferate in England and Scotland.

The Gunpowder Plot

The protagonists of the gunpowder plot, especially its leader Robert Catesby, had been trying to the overthrow the monarchy for years. Catesby had taken part in the Essex Rebellion in 1601 against Elizabeth. In 1603 he sent a delegation to Spain to try and convince King Philip III to invade England, promising the support of English Catholics. Among the men sent to Spain was Guy Fawkes, a committed Catholic who had been in the thick of the European religious wars for many years. Fawkes fought alongside the Spanish in its war against the Dutch Republic, and against France until 1595.

By 1604 it was obvious that no help could be expected from Philip III. In May of 1604, the five core conspirators met for the first time to discuss Catesby’s idea to blow up the Houses of Parliament. This would kill the King, who would be present at the state opening of Parliament, and also virtually the entire Protestant aristocracy, the Bishops of the Church of England, members of the Privy Council and senior figures in the judiciary. Their plan was to then install the King’s daughter, Elizabeth, as Queen.

The scheme developed throughout 1604, and more people were added to the plot. It isn’t known for sure how exactly the men gained access to the undercroft beneath the House of Lords. There are accounts from the confessions of Wintour and Fawkes that mention a tunnel to parliament from a house they were renting. However, no such tunnel has ever been found. It is established, though, that they found and rented the room, to which they began to stockpile with gunpowder.

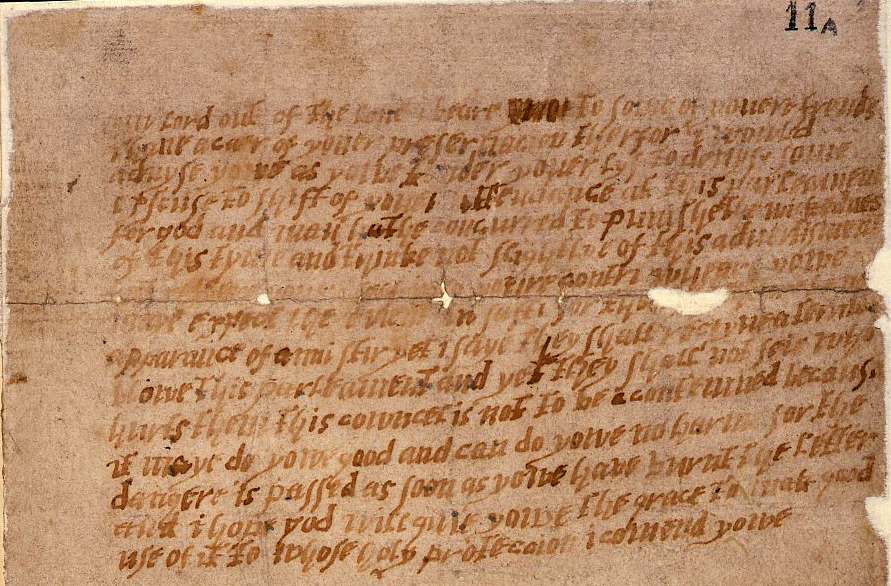

The Monteagle Letter

A central concern of the plotters was the murder of innocents, especially Catholics. One such Catholic Lord, Monteagle, came into the possession of an anonymous letter warning him to stay away from Parliament on the opening day, ‘for God and man hath concurred to punish the wickedness of this time’. Once the King returned to London from a hunting trip on 1 November, he was shown the letter.

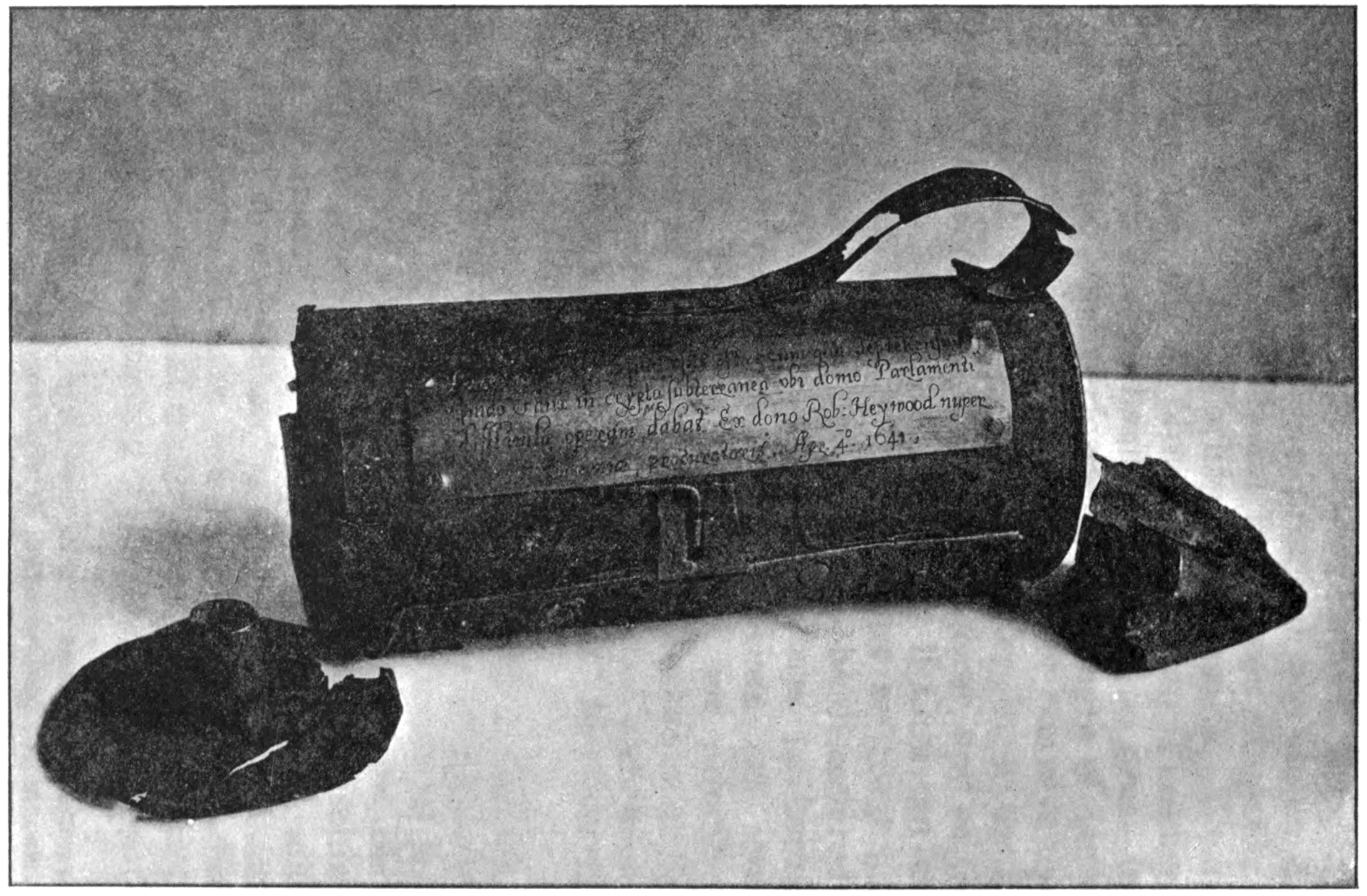

James focused in on the line, ‘For though there be no appearance of any stir, yet I say they shall receive a terrible blow this Parliament; and yet they shall not see who hurts them.’ He believed this to be a reference to some sort of planned explosion and ordered a full sweep of the Parliament buildings. The undercroft was searched twice. Fawkes was found next to the gunpowder, hidden under firewood that he claimed belonged to his master. Returning to the undercroft late on the night of 4 November, Fawkes was discovered once more and arrested. The lamp he was carrying at this fateful moment is now in the Ashmolean Museum.

A Tradition is Born

The whole conspiracy was rolled up in the weeks following 5 November. Many of the plotters, including Fawkes, confessed under torture and were duly executed. Fawkes managed to escape the agony of being quartered by jumping from the gallows, breaking his neck and ending his suffering.

In the new session of Parliament, the Observance of 5th November Act was passed, remaining on the books until 1859. The day was originally infused with fervent anti-Catholic rhetoric. ‘Gunpowder Treason Day’ as it was known, was used to invoke the threat of Catholicism. Addressing the House of Commons on 5 November 1644, Charles Herle claimed that Catholics were tunnelling "from Oxford, Rome, Hell, to Westminster, and there to blow up, if possible, the better foundations of your houses, their liberties and privileges".

Over the next 420 years, the tradition of lighting bonfires has travelled in and out of fashion. For a significant part of its history, Guy Fawkes night has been accompanied by significant disorder. In Lewes and Guildford, annual rioting terrorised the local populations, demanding a coordinated response from police. By the Victorian era, the anti-Catholic fervour had largely gone from proceedings, and effigies that were burnt began to include other unpopular political figures. In the modern era, figures from pop culture and the news have been burnt on Guy Fawkes bonfires.

This year, if you’re looking at the fireworks in a muddy field, pause for a second and think of the men who thought they were about to usher in a new age from a dank cellar under parliament.

Bonfire Night Celebrations in Oxfordshire

Friday 1 November

Didcot Fireworks Spectacular, 4-9pm, Loop Meadow Stadium, Didcot

Saturday 2 November

Oxford Round Table Charity Fireworks Display, 4.30-9.30pm, South Park, Oxford

Wallingford Bonfire and Fireworks, 6-8pm, Kinecroft, Wallingford

Tuesday 5 November

Kidlington Fireworks, 6pm, Stratfield Brake Sports Ground, Kidlington

Wolvercote Fireworks, Barbeque and seasonal treats from 5pm, fireworks from 7pm, The Plough, Wolvercote, Oxford

Saturday 9 November

Abingdon Bonfire & Fireworks 2024, 4-9pm, Abingdon Airfield, Dry Sandford, Abingdon-on-Thames

Thame Fireworks Display 2024, 5pm, Chinnor Rugby Football Club, Thame