Those of you who are loyal followers and diehard fans of my writing (yes, both of you) may be accustomed to a focus on a newly established city centre restaurant, an old-guard rural dining pub with a new menu, or a hotel with an ambitious kitchen. This review, however, is not of one particular building – indeed, the following words may apply to your own dining room, if you are that way inclined.

In the past, I've always thought of the home-visiting chef as quite a bizarre concept, as for me, part of the appeal of spending your money on dinner is the atmosphere, the occasion, and the ritual of visiting a restaurant. But then – and I say this in total sincerity and not on any form of commission – Andrew McKelvey is not your normal chef.

At this point, it's worth talking about the story of the man himself. Andrew (or 'Mac' to his friends, customers, and everyone else) has had a ludicrously colourful career. After entering the trade at 16, Mac did the usual long, hard graft in restaurant and hotel kitchens around London, then moved to New Zealand. After six months on the other side of the world, he fell ill and had to return to the UK for what would be one of the first heart transplants performed after the introduction of crucial immunosuppressant drugs. After the life-changing and, at the time, perilously risky surgery, he got straight back in the kitchen, picking up techniques, methods and inspiration from a long list of high-end restaurants – often switching to a different employer after 9 months or less. The rationale behind his fast-paced career shifts was to remain nimble as a chef: "If I became a little bored and stopped learning from the people around me,” Mac tells me as he stands in his vast preparation kitchen in Woolstone, near Faringdon.

It has now been 34 years since the transplant, and Mac has more ambition, drive and fresh ideas than a chef half his age. So, a resounding medical success and a source of inspiration, but what of his art?

Whilst you can tailor Mac's service to fit your desires, it would be churlish not to start the evening with canapés, particularly when they are of such exceptional quality. Rich, dense tuna fillet came as a carpaccio, laid over coconut risotto and topped with a subtle wasabi purée and crisp shallot for textural contrast. A second carpaccio – of beef – was possibly the highlight, delicately served atop a preposterously moreish marrying of truffled celeriac and parmesan crisp. Fried quail's eggs were backed up with earthy wild mushroom purée and chives, and the most delicate of sea bass adorned a sharp pickled vegetable ceviche. The experience was nothing short of a delight.

Whilst you can tailor Mac's service to fit your desires, it would be churlish not to start the evening with canapés, particularly when they are of such exceptional quality. Rich, dense tuna fillet came as a carpaccio, laid over coconut risotto and topped with a subtle wasabi purée and crisp shallot for textural contrast. A second carpaccio – of beef – was possibly the highlight, delicately served atop a preposterously moreish marrying of truffled celeriac and parmesan crisp. Fried quail's eggs were backed up with earthy wild mushroom purée and chives, and the most delicate of sea bass adorned a sharp pickled vegetable ceviche. The experience was nothing short of a delight.

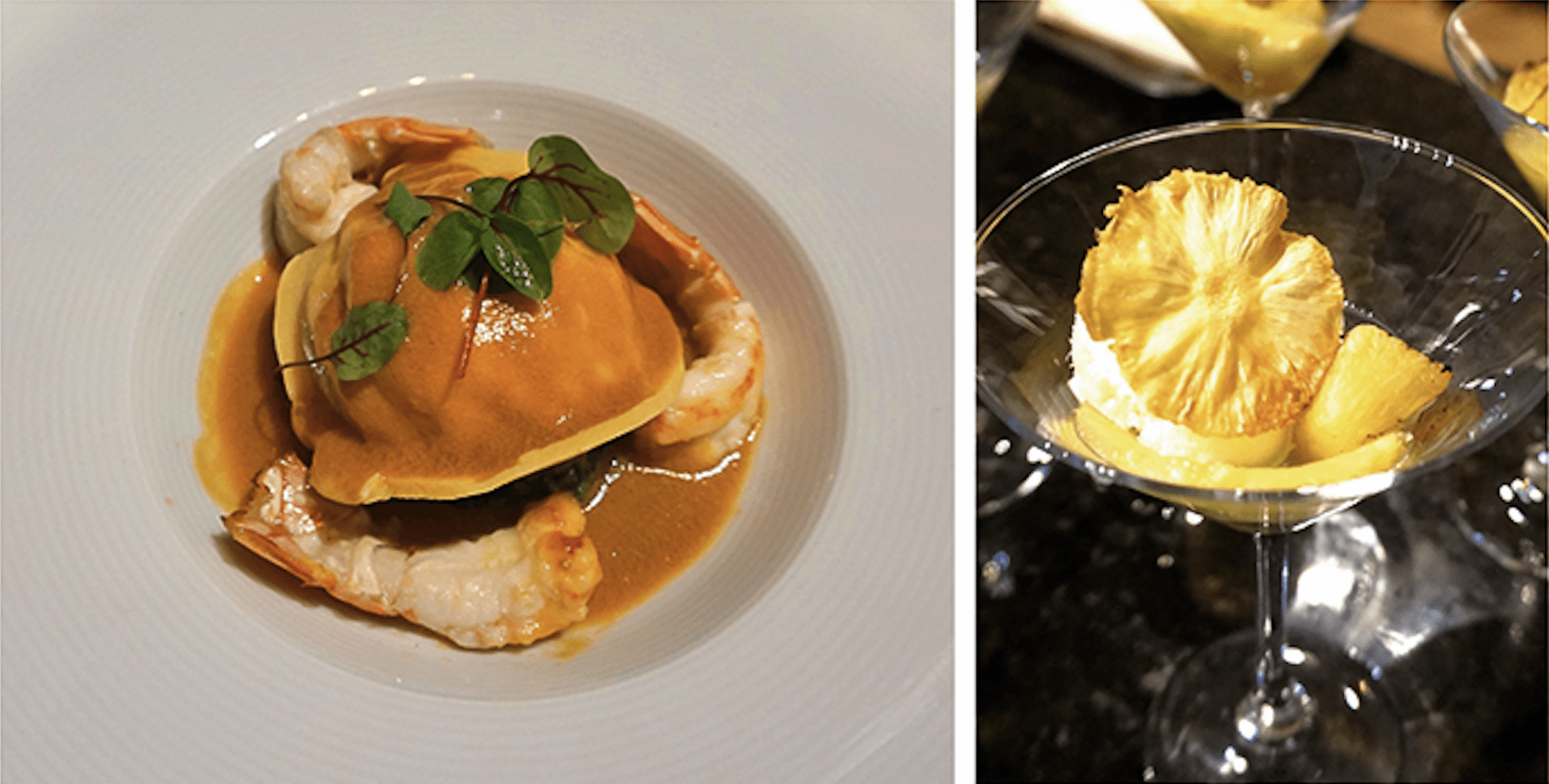

With appetite suitably whetted and a few glasses of champagne deep, it was time to get stuck into the main menu. A single, meaty scallop was given the quiet lift it deserved by celeriac ‘noodles', wasabi crème fraiche and leafy seashore vegetables, and a velvet-smooth sea bass and prawn mousseline ravioli only needed a splash of shellfish bisque and a sautéed langoustine.

Perhaps one of the most impressive aspects of the service is how quiet and relaxed Mac's process remains throughout – no noisy kitchen dramas here.

Perhaps one of the most impressive aspects of the service is how quiet and relaxed Mac's process remains throughout – no noisy kitchen dramas here.

Life is worth living...

Mac's main course was close to unimprovable. A lean cannon of lamb was rolled in smoked

garlic and rosemary and served a beautiful shade of pink, yielding to the knife and impossibly flavoursome. Fondant potatoes were tender and roasted shallots were sweet.

One depressing aspect to the evening was the slow realisation that everything else that comes out of my kitchen is, from now on, going to seem wholly unimpressive. Mac's pre-dessert and dessert proper were perhaps the best showcases of the two sides of his prowess: one forward-thinking and imaginative use of ingredients, and one stone-cold classic as a display of culinary technique. The former was pineapple, four ways: a translucent-thin slice of raw fruit, in a martini glass, is joined by roasted pineapple pieces, Mac's own pineapple sorbet, and a delightful pineapple crisp. The latter was the favourite of anyone with good sense: tarte tatin, with the soft butter-caramelised apple giving way to crisped pastry – the kind of dish that affirms that life is worth living.

By the time we reached the end of the menu, I entered my kitchen expecting to witness a battlefield of cooking equipment, ingredients and the usual post-dinner disarray. To my astonishment, the surfaces were spotless, Mac's equipment was already back in the boot of his Range Rover, and after a handshake and a grateful farewell, he'd disappeared as quickly as he'd arrived.

After retiring for a digestif or six, I'd rarely felt more impressed or satiated. Comparing this sort of experience to restaurant dining is an unfair comparison - transforming your own home into a bon vivant's paradise for an evening is an entirely separate craft. And with Mac at the helm, there are few more enjoyable ways to spend your money.