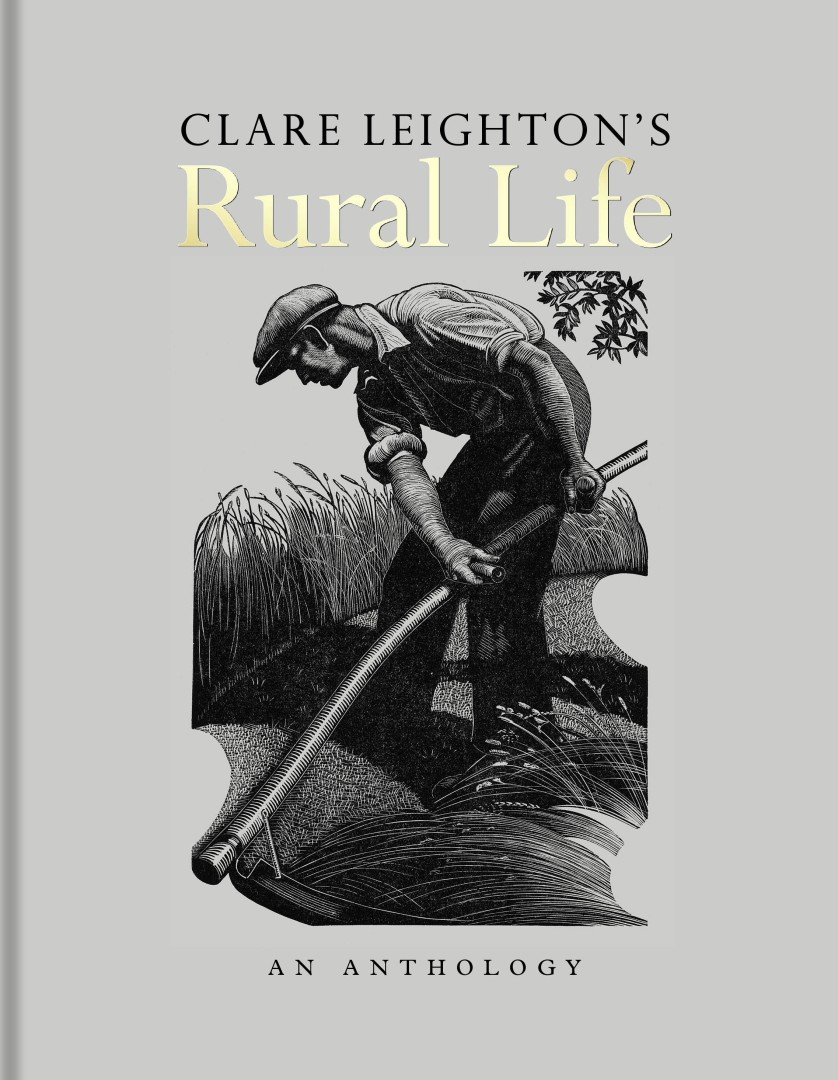

Clare Leighton (1898–1989) was one of the most prolific and highly regarded wood engravers of her time, leaving behind a body of work which reflected her experience of rural life in Britain and North America. During the 1930s, as the world around her became increasingly technological, industrial, and urban, Leighton portrayed rural men and women and the ancient methods they used to work the land that would soon vanish forever.

Her two best-loved publications, The Farmer’s Year and Four Hedges, reflect a passion for the British countryside. Less well known are her books illustrating and describing rural life in the United States of America, where she emigrated and became a naturalized citizen in 1945. Leighton also spent time in Canada with the logging community. Her wood engravings depicting lumberjacks in the snow-covered forests of Canada are some of her most evocative prints.

An anthology of her works, Rural Life (Bodleian Library Publishing, Autumn 2023) reflects Leighton’s lifelong fascination with the virtues of the countryside and the people who worked the land. Introduced and edited by her nephew, David Leighton, it includes beautifully reproduced extracts of her writing as well as her woodcuts.

The following extract on cider-making in October is reproduced with kind permission by Bodleian Library Publishing

October - Cider-making

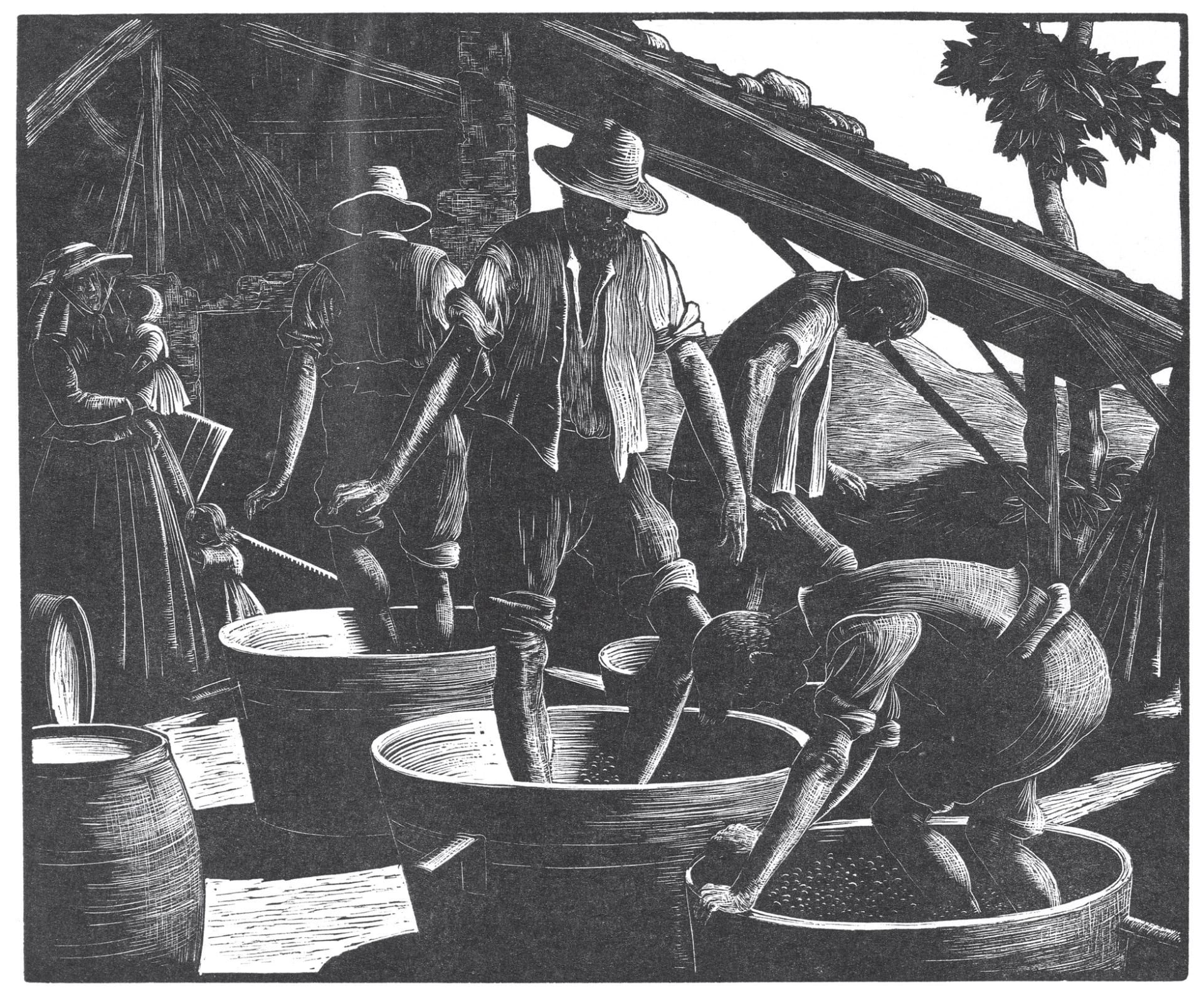

Round and round in a Devon barn plod two old men throughout the golden hours of an October day. Our eyes, accustomed to the bright sunshine outside, can at first see nothing in the deep shadow of the barn but vague shapes moving with regular tread to the sounds of creaks and wrenchings and clanks. Out of the background of these sounds comes a little trickling gurgle, like a running stream. As we grow used to the gloom, shapes solidify out of the dark of the barn. The light catches the screw of the enormous wooden cider press, its edges smoothed and softened by age. The same light sparkles upon the metal bands of the tubs. Shafts of gold dart through the walls of the barn at odd places, where the woodwork has decayed, picking out here the haft of a spade, there a pile of pressed apple pulp or a dust-filmed bottle.

Round and round trudge two old men, leaning heavily on the winch. The red Devon earth cakes their gaitered legs and smears their clothes. They are themselves mere upright pillars of this earth, and when they talk to each other, in unintelligible grunts, their speech has an earthy sound.

As hour after hour the winch turns the screw, the sacks of apple pulp flatten and diminish, and after a time the trickling gurgle of juice grows feeble and uncertain. Creaking and groaning, the press plays a sleepy bass to the grunts of the two old men and the shuffle of their earth-caked boots. Age is upon it all; we are outside of time. These men must have been trudging round and round before our grandsires were born; and they will be trudging still when we ourselves are dead. Only the shifting of the sunlight on the floor of the barn shows us that time has not paused. While we watch, the sun quits the metal band of one of the tubs and strokes the basket of unpulped apples by its side. In the blackness of the barn it catches at the wooden cogs of the enormous wheel that the donkey turns to crunch and pulp the apples, reducing their crimson and green and yellow variety to a uniform brown mass. Hens stray into the cider barn, each one bringing in front of her a little purple shadow. They peck at the apple pips among the men’s feet. As the day goes on, the smell of the apple pulp grows sickly in its sweetness. Still the old men trudge.

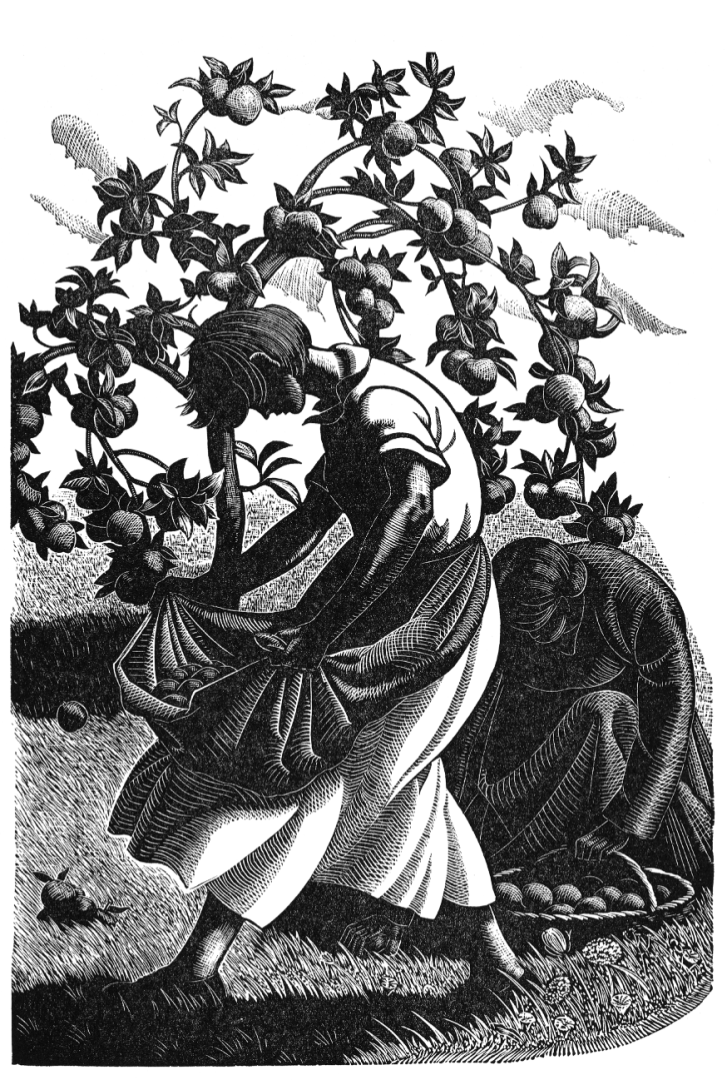

Outside in the sunshine everything shimmers. Gold falls in splashes on the branches of the elm, and the beechwoods are turning a burnt brown. Scarlet berries spot the hedgerows, converting the red of the Devon earth to a dull crimson. Away on the open stretches of Dartmoor, the wind is already bleak and unfriendly and the ponies huddle for warmth at night under the stunted bushes; but here in this soft land of shelter, where, round and sudden as a child’s imaginings, rise the little wooded hills, the autumn is still kind in its touch. It is gentle and golden, and if a few leaves have started to fall from the trees, it must have been by accident. There is as yet no hint of winter, for the film of frost upon the ricks vanishes when the sun rises. When it beats upon the hedgerows the dewdrops disappear from the spiders’ webs that bind one curl of traveller’s joy to the next.

Outside in the sunshine everything shimmers. Gold falls in splashes on the branches of the elm, and the beechwoods are turning a burnt brown. Scarlet berries spot the hedgerows, converting the red of the Devon earth to a dull crimson. Away on the open stretches of Dartmoor, the wind is already bleak and unfriendly and the ponies huddle for warmth at night under the stunted bushes; but here in this soft land of shelter, where, round and sudden as a child’s imaginings, rise the little wooded hills, the autumn is still kind in its touch. It is gentle and golden, and if a few leaves have started to fall from the trees, it must have been by accident. There is as yet no hint of winter, for the film of frost upon the ricks vanishes when the sun rises. When it beats upon the hedgerows the dewdrops disappear from the spiders’ webs that bind one curl of traveller’s joy to the next.

The wood pigeons begin to haunt the lanes where the oak trees drop their harvest; their crops are swollen with acorns. The red squirrels prudently bury their store of nuts and acorns. The trees rustle as they leap and run. They look like flaming autumn leaves that have detached themselves from their branches. In the village thin spires of smoke, of the colour of a blue Persian cat, rise vertically into the sky; for rakes and brooms are at work upon the refuse from cottage gardens, and bonfires bring with them the smell of the fall.

Through the sleepy glow of the October afternoon the two old men in the cider barn trudge round and round, grunting to each other from time to time. The sun has now swung over to the far end of the cider press and catches new forms and objects, leaving in shadow the cider barrels that earlier in the day it had emblazoned. A cat emerges from the shade, lazily stretches herself, and takes her seat in the path of the sun. Nothing else has changed.

Outside in the farmyard the sun has moved above the roof of the cowshed opposite and gilds the figure of the man thatching a rick. Over everything it throws soft-edged shadows, lilac against the gold of the autumnal light.

In the fields the root crop is being harvested. We have grown accustomed throughout the summer months to their bitter acrid green, and as the men ‘get off’ the mangolds there is a dull, uniform look about the landscape that more than anything else tells of approaching winter. By the Lower Farm they are lifting beet. The men go down the ridges, drawing the roots from the soil. With the economy of movement that characterizes all work on the land, they cut off the leafy tops of the beets as they stoop, and throw the roots in a line. The cart follows them, accompanied by two men who rapidly and rhythmically lift the beet with both hands and fling them into the cart. It looks like the first sketch of some old folk dance. Now the long autumn twilight falls; mists cling to the fields, and flaming sunsets fire the countryside, tree trunk and waggon, hayrick and ploughboy alike. The sun, which in the summer evenings burnished the roof of the farmhouse as it set, halts now in the south and ends its dwindling path behind the village church.

Down the lane comes a crowd of schoolchildren. Purple-stained mouths and hands reveal that they have been blackberrying on the common. They hurry home in the darkening twilight.

Against the sunset sky the cider barn stands dark and dignified. The sun no longer blazes on metal and shiny surface; there is a brown mellowness reflected from the crocus glow outside.

The gloom emphasizes the stateliness of the barn. It stands like an old cathedral; the leaping wooden beams in the high roof are its vaultings; the cider press its altar. The gloom deepens for its unhallowed vespers. Bats drop from its roof and rush with a shrill cry into the dusk.

Night falls on two old men, still trudging.

Clare Leighton’s Rural Life An Anthology, edited by David Leighton is due to be published by Bodleian Library Publishing on 19 October.

Order your copy at bodleianshop.co.uk