Matthew Kelly, David Yelland, and Philip Franks talk Alan Bennett and The Habit of Art with Sam Bennett

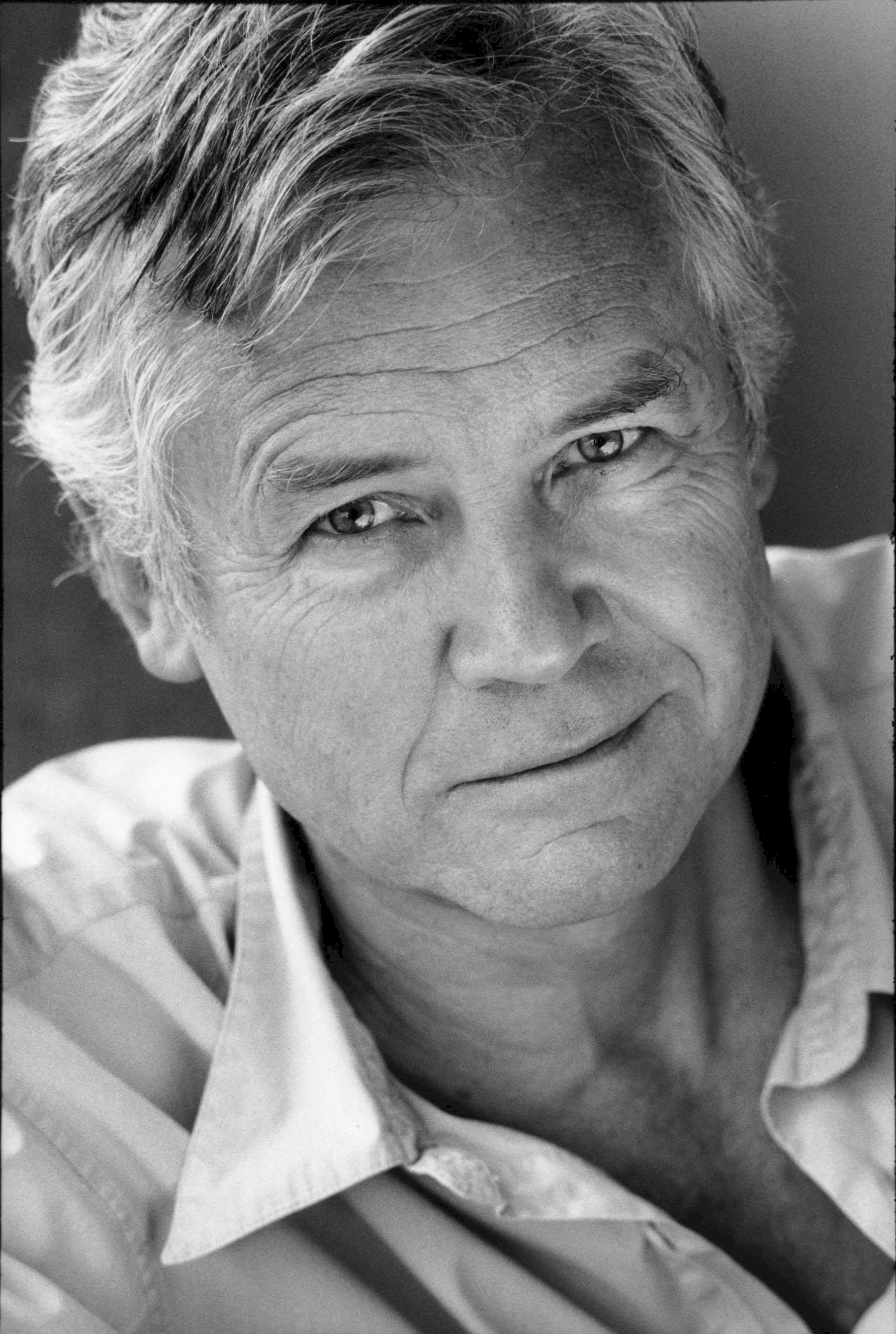

Matthew Kelly

When Meghan Markle and Prince Harry got married, self-confessed television addict Matthew Kelly started watching Suits, in which Markle plays Rachel Zane. “It’s marvellous,” he says in the Randolph's Worcester Room. “I’m on series seven, episode three,” he continues in a rich and somewhat mystical tone. “Do you know how many hours’ telly that is?” The last time he checked – back when he was enjoying series six – he saw that he’d spent over 100 hours of his life watching Suits.

Insofar as his own performing goes, the only time I’ve seen him onstage was at Liverpool’s Everyman Theatre in 2014, as Sir Toby Belch in Twelfth Night – the production that reopened the theatre after a lengthy rebuild. Kelly was actually a member of the Everyman’s 1974 company, alongside Nicholas Woodeson who also returned to the theatre for Twelfth Night in the role of Malvolio. For that show the pair of them shared a dressing room. “I said to him, ‘Nick, if they’d said to you 40 years ago that you’d be back here 40 years later peddling the same old sh*t, what would you have said?’ He said, ‘Shoot me now.’”

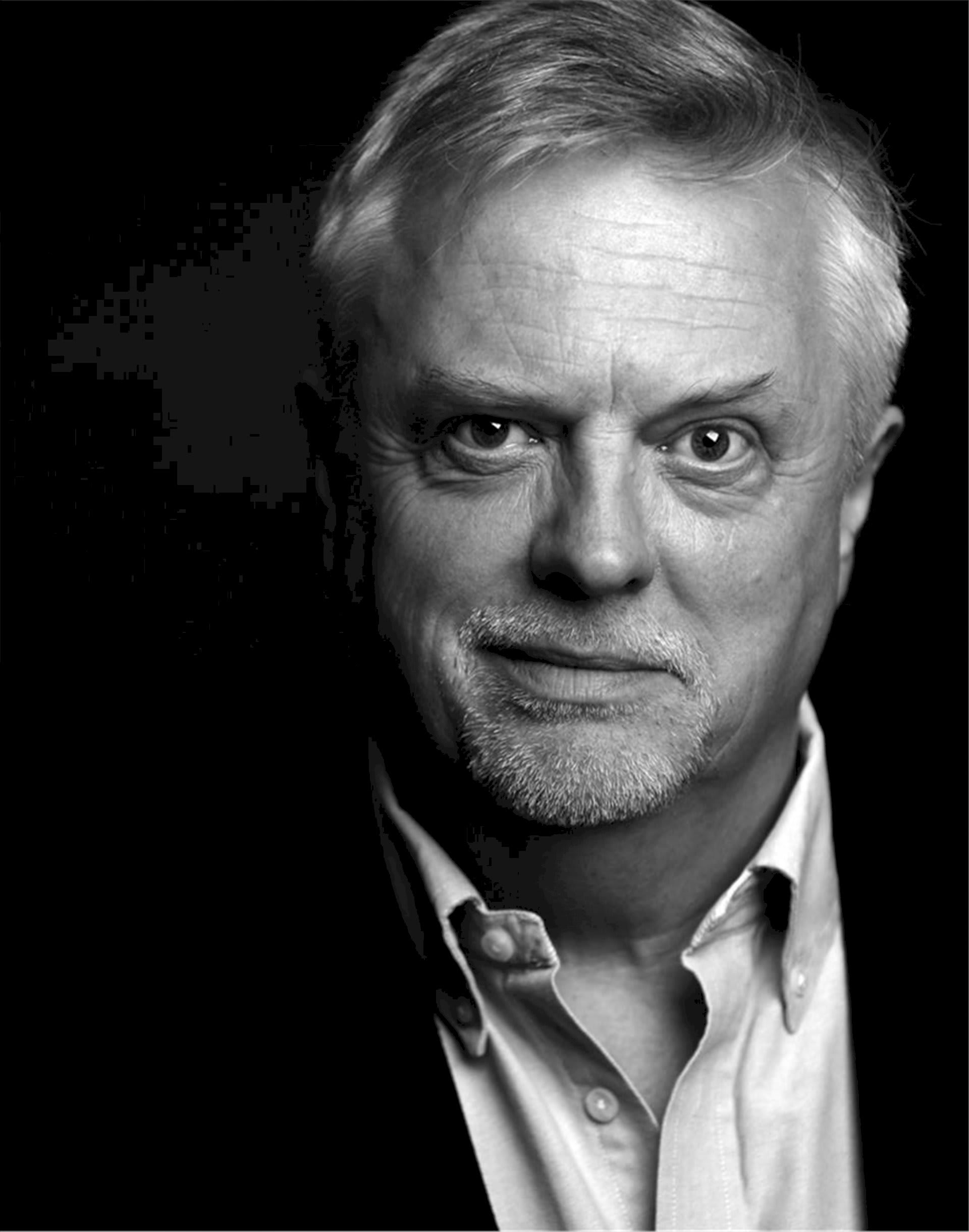

David Yelland

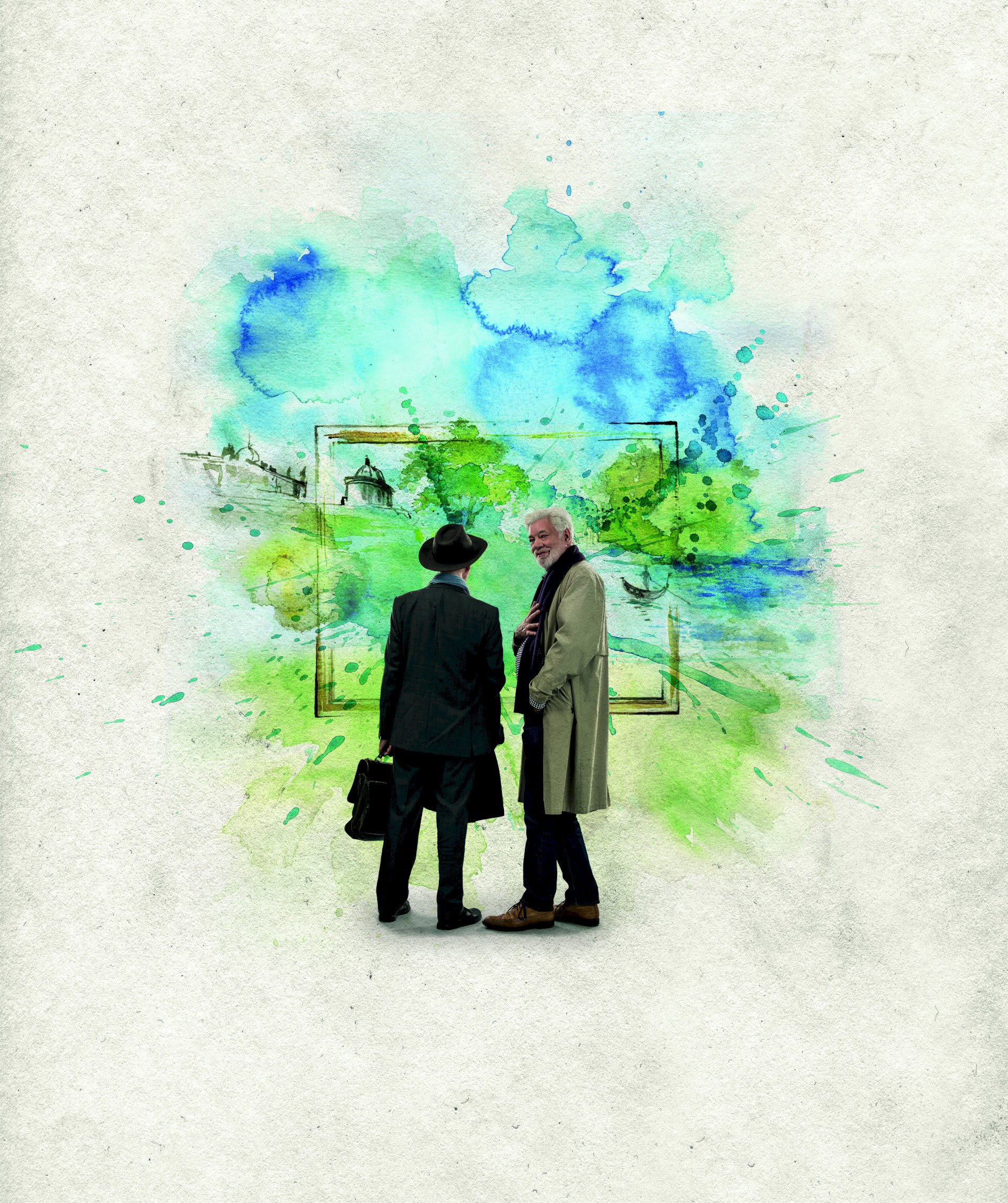

Next to him on the sofa is David Yelland. Both are starring in the first revival of Alan Bennett’s The Habit of Art, touring to Oxford in September. Kelly will portray WH Auden and Yelland Benjamin Britten in a fictional meeting between the poet and the composer. “Bennett’s a wonderful writer,” says Yelland. “There’s a particular angle he takes to whatever subject he is tackling, and I think his take on these two extraordinarily brilliant creative people is fascinating.”

“It's funny and moving,” his co-star states, “sometimes at the same time. He also talks a lot about sex in a very earthy manner – you're kind of relieved when people talk about sex like that.”

After hearing Kelly say that the two sitting before me don’t have to retire because “there's always some old f*cker to play”, I ask if they’re both as busy now as they’ve ever been as actors. “I was doing a tour of Pride and Prejudice,” Kelly (who “does very well for work”) says, thinking back to when said tour stopped in High Wycombe and a producer came to see him. “She wanted me to do this play – it was opening in Dundee. I said, ‘No, I don't want to do it, I don't like the play.’ She said, ‘Oh please come and do it.’ I said, ‘I really don't want to do it.’ She said, ‘Oh please, please come; I can't get actors to tour now.’ And I thought: 'That’s how I get the work.’ I thought I was brilliantly talented – I was so upset.” Did he do the tour in the end? “Did I heck – Dundee, are you mad?” I should maybe mention he then praises the Scottish city – or at least part of it. “I would quite like to go there because it’s got that fantastic V&A. It's shaped like a boat, it's beautiful, it's stunning, it's reviving Dundee, yeah, it's a masterpiece of architecture – I don't know what's inside.”

Yelland has got a bit choosier about roles as he’s got older. “You don't necessarily want to do everything that comes your way, whereas when you're just starting and nobody knows who you are at all, you kind of have to take whatever's going.”

Philip Franks

Soon after, I’m informed Kelly has another interview to give, and that The Habit of Art director Philip Franks will be taking his place. But he doesn’t have to disappear just yet. What career advice would they give their 20-year-old selves? “Only do it if you love it,” Yelland promptly comes back with. “To thine own self be true.”

“Oh that’s a good one,” says Kelly. “I would say to other actors who are starting out, there's a difference between want and need. If you want to do it, you might do it; if you need to do it, you will do it. And what you must do is everything. Go in amateur shows, semi-professional shows, tatty shows, just for the experience of being onstage. The trick is confidence, it's not a confidence trick, it's a trick of confidence, and you get that confidence by doing it over and over again. Does that help?”

I tell him it’s been a pleasure, that I’m sorry he’s got to go, and that I personally don’t know where in the room he’s going. Nowhere right now, seemingly. “Keep going.”

I return to The Habit of Art and ask whether either of them have seen the play before. Neither has. “I think,” Yelland tells me, “that to some extent it's a disadvantage, and to some extent it’s an advantage – you don't have preconceptions.” Kelly has time to tell me he was at college with Richard Griffiths who acted as WH Auden during the play’s premiere at the National in 2009, before the time for him to go really does arrive.

"Come and see the show"

“Come and see the show,” he departs with, “and we'll meet in the bar afterwards for a bevvy – I'm always in the bar afterwards, it's the law.””¯

His director soon fills the space he’s left on the sofa next to Yelland who’s worked with Philip Franks twice before. “He’s a brilliant director,” he says. “The fact that he is also a brilliant actor enables him to hone in on what an actor needs at a particular time. It's a tremendous plus, because all actors – it doesn't matter how well-known – need immense reassurance, and an actor directing understands that.””¯

Franks says, “It’s absolutely not about coming in and thinking 'I could do it like this' and wanting to get up and prance around – I never feel that as a director. What I try and do is create an atmosphere in a room where actors feel relaxed and secure enough to risk a little bit more than they might ordinarily. If you feel that you're somehow”¯being tested by a director, then chances are you'll clench a bit and just do what you know you can do; whereas if you feel free and a bit giggly, you might well try and do something that goes a bit outside of your comfort zone. Without being too precious about it, actors don't respond very well to cruelty or insult, who does? While some directors would think they would, I don't think that. I like a happy room, where people are pleased to be there and where they look forward to turning up for work, and where the egos are less than the joy of making something as a group.””¯

The Habit of Art

Regarding The Habit of Art specifically, I wonder in what ways it’s relevant. “We all have our emotional relationship with our work,” he says, “and it is about that. We all,” he resumes, “whether we admit it or not, are intrigued and exercised by the relationship our sexuality has with who we are in the world; how we express it, how it effects what we do, particularly in a creative industry; whether your sexuality inhibits you or whether it allows you an expression you might not otherwise have had. It deals with that.”

Other themes include success and failure, and playing “the long game” in a creative trade where people believe success or failure to be instantaneous. Such immediacy, he says, is not so in the case of those crafting for the long haul. “It's what we do over a period of many decades, and that has its ups and downs, and its pains as well as its pleasure. Alan Bennett knows that inside-out, but he also knows it with a profound sense of humour. He is witty to the core of his being, so it's not doomy or sentimental or self-indulgent or miserable, it's always funny. But it's piercing and humane and investigative – all of which are completely relevant. You don't need a degree in music or poetry to know who these men are. This is one man, Auden, who feels himself to be at the end of his life and a forgotten man. And another man, Britten, who is absolutely at the height of his creative powers but staring death in the face and also has a very complex relationship with his sexuality that makes him profoundly uncomfortable but, you could say, applies the pressure that turns the coal of experience into the diamond of art.””¯

The Play

The play is “not a hard watch”, he says, “but it requires you to think – art should be tough, challenging and make you think.” The Habit of Art is not about “just sitting back and having your buttons pushed like at a musical. And anyway, a good musical like a Sondheim, Fun Home or Hamilton gets you absolutely engaged and thinking. What you want from the theatre is to be sitting forward in your seats, don't you?”

I believe so. And hopefully this particular offering has its audiences as hooked as Matthew Kelly is by Suits.