The Snowman was aired on Christmas eve in 1982 as a showcase programme for the new Channel Four, dancing light-footed on our screens with festive cheer. Thirty years later, his companion The Snowdog made an appearance. Raymond Briggs is the original author, illustrator and the name most commonly associated with The Snowman, however it was Oxfordshire Artweeks animators Hilary Audus and Joanna Harrison who picked the original character from the pages of the book and brought him to life on film, later developing his canine companion.

“Back in the early 1980s, a colleague of mine Jim Duffy, had twin girls,” Hilary explains, “He’d been reading The Snowman to them and suggested it would make the perfect animated short: that was where it all started. We extended the original story to add the flying scene, the party at the North Pole with Father Christmas, and the scarf.

Joanna and I drew all the pictures, along with a team of other animators, and also had an incredibly important team of ‘renderers’ who coloured in all the drawings individually, adding colour and texture to each acetate layer. They worked with wax crayons which had to be kept in the fridge on rotation as they were warmed by the hand using them. Because each frame is hand coloured so is very slightly different to the one before it, when you watch The Snowman each scene appears to shimmer: it’s a wonderful effect that you can’t recreate with a computer.

We produce the animation using multiple layers. When we animated the barn owl, for example, the background was on paper, a branch on an acetate sheet, the passing motorbike and the body of the barn owl on two more, and the owl’s head – because it turns around – was on another.

In The Snowman, there’s a motorbike sequence that lasts a little over two minutes, with 12 frames to draw per second, that’s more than 1,500 motorbikes. Fortunately, some of them were very small!” she grins. “In total, we used 200,000 pieces of paper.

Thirty years on, the animation process has changed significantly. It was important though to keep that hand-coloured shimmer which threw up some challenges. We ended up scanning the drawings for each frame, breaking them down into shapes to be hand-rendered, and then added back in digitally.

Raymond Briggs never wanted there to be a sequel, but as Channel Four’s thirtieth anniversary approached, he mellowed. Joanna and I first had to decide what the narrative would be. The story needed to include loneliness and loss alongside friendship, whilst also being bright and uplifting for Christmas. We asked ourselves why the Snowman might come back, wrangled over whether to use a boy or a girl and pondered over what would have changed in the environment. A single parent family moves into the old house, and the sequel is more built-up. We also agonised over the possible inclusion of a flying scene that was both true to the original whilst different, but in the end, we opted to animate an old-fashioned aeroplane.

It took a little time though to get the design of the Snowdog himself right. Snuggly colourful socks made great dog ears, and then once we had our third character, the plot flowed easily.

We had considered other pets than a dog – there might have been a hamster instead!” chuckles Hilary. “But Joanna and I both have dogs at our feet in our studios so perhaps it was inevitable!

It was wonderful to create a character that I’d have loved as a child. I loved EH Shepherd’s illustrations of Winnie-The-Pooh; the Beatrix Potter characters, and Wind in The Willows were other favourites. I was always drawn to animals and would be given a new stuffed toy every birthday and Christmas. One year I received a doll instead, but she was rather a disappointment! My panda was the matriarch, and every night I slept with them all tucked under the blanket, from Selina Seal to a tin duck! It was in the days before central heating and I couldn’t bear the thought of them being cold.”

At school, Hilary was most interested in art and biology and with botanists for parents, imagined she might become a botanical illustrator. “My father was a very wise man,” she laughs. “and he wasn’t convinced, so he organised an afternoon of work experience for me at the Natural History Museum. I was expected to draw the exact likeness of a dried-up old fish: however, I wanted to add life and character to it. I was clearly better suited to animation!”

As a child Hilary also loved making three dimensional models from balsa-wood, including a version of the classic map of Winnie-The-Pooh’s Hundred Acre woods. Over the past decade, Hilary has increasingly worked with clay, creating stoneware animals in her rural studio. She revels in the shape and form of each creature, their elegant silhouettes and the sweeping curves of their anatomy.

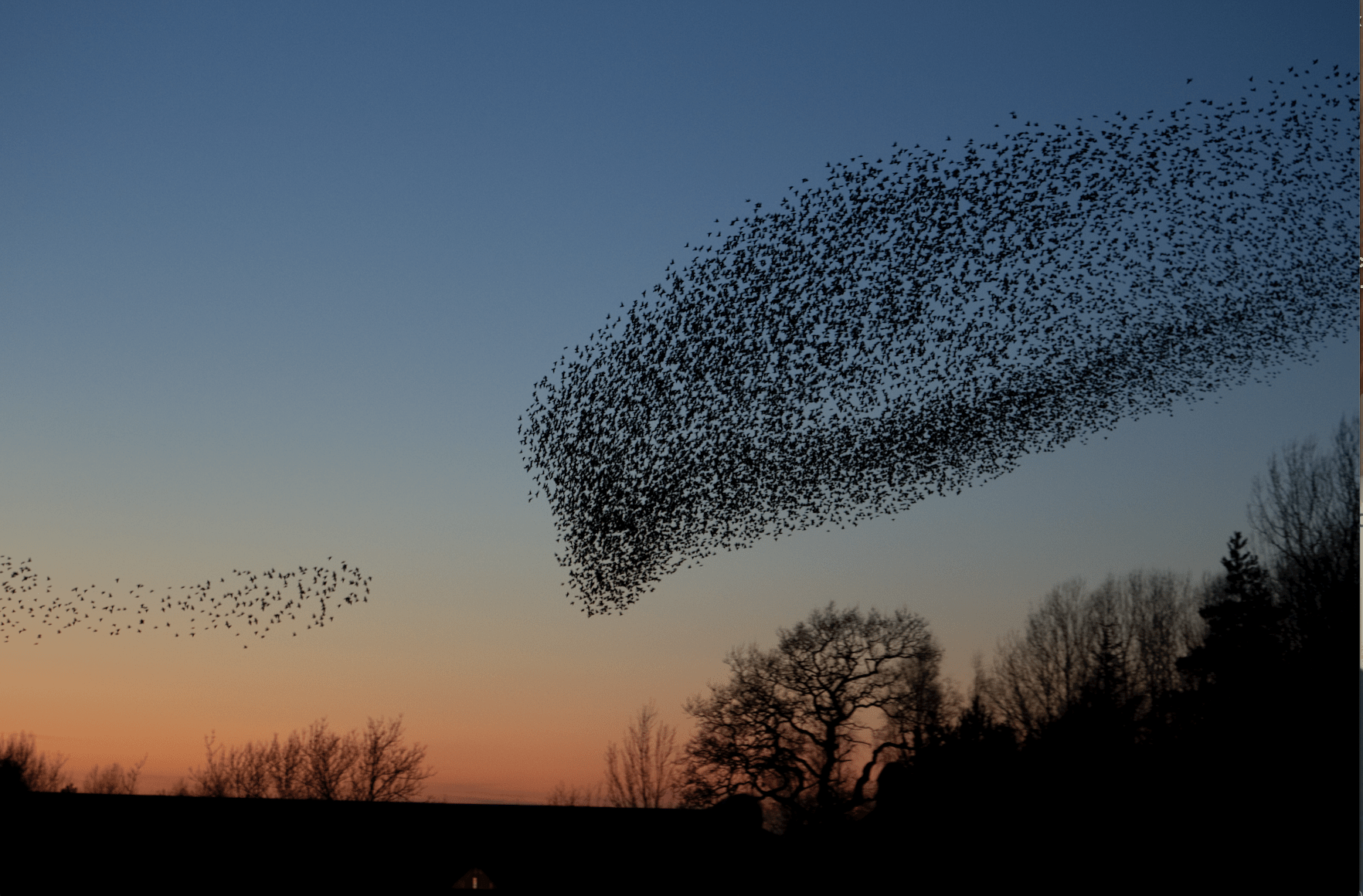

As an animator, she explains, she studied hours of videos, freeze-framing the different ways animals move, studying horses galloping, to birds flying from every angle. Over the years, this developed into an instinctive feel for the underlying musculature and the way the limbs move which translates directly into sculpture. With a naturalist approach, Hilary’s birds and animals include those seen in the English countryside, alongside fantasy birds with spots and sock heads and other beasts.

Unusually, perhaps, Hilary adds most of the colour to her pieces after firing. This careful composition is a contrast to many ceramicists, who love the serendipity of experimenting with glazes and colours in the kiln, and a mark perhaps of her animator roots.

Hilary’s studio is in a charming spot, overlooking a large wildlife pond bursting with waterlilies and marsh marigolds, water mint and dragon flies which she tames from a bright green rowing boat evocative of Ratty and Mole’s in Wind in The Willows. The pond is home to several species of newt, including the rare great-crested variety, and it once housed a water vole, an endangered species.

“I was sorry to realise recently, how many of the animals I have captured in clay are on the endangered list; the puffin, the curlew, the rock-hopper penguin and the hedgehog too. I’ve always been an eco-warrior,” she says, “and so all the proceeds of my sculpture, on show for Oxfordshire Artweeks each year and in several galleries around the south east, go to RSPB and WWF.”

An exhibition of some of the original illustrations from the book and film The Snowman and The Snowdog are on show at Henley’s River and Rowing Museum (until 19th January 2020).