"If you talk to a man in a language he understands, that goes to his head. If you talk to him in his language, that goes to his heart." – Nelson Mandela

Beyond the language barrier, we can take Mandela’s statement to reflect how our choices of words can affect the way in which we are understood. We change our tone based on time, place and situation. In some cases, we have to convey tragedy, failure and disaster – but how? Should it be glorified and romanticised, or remain factual and impassive?

On a national level, politicians use speeches to carry the weight of catastrophe. The wrong words can trigger wars, violence and chaos, the right ones can inspire and unite. From “I have a dream” to “We shall fight on beaches”, leaders have inspired during times of pain.

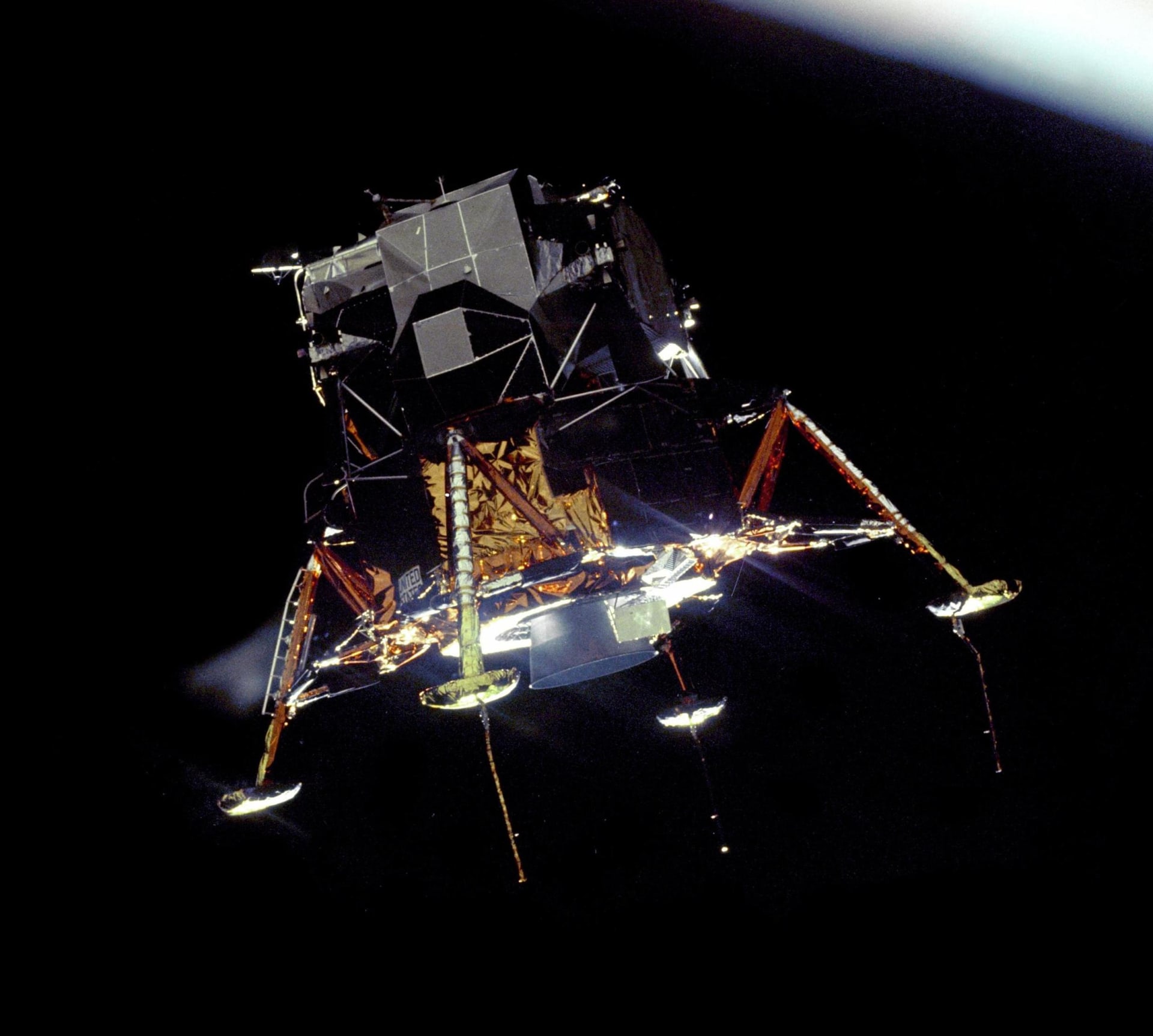

“Because of what you have done the heavens have become a part of man’s world,” were the words said by Nixon to the 1969 Apollo 11 space crew after the successful moon landing in what was termed the ‘longest-distance phone call’. Armstrong’s words as he stepped into history scarcely need repeating – “That’s one small step for man. One giant leap for mankind.”

Armstrong’s famous words actualised a dream laid out by President Kennedy in 1962. Kennedy’s speech, delivered at Rice University, elevated the importance of space discovery and transformed it into a nationwide dream: “We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard.”

But what if the giant leap ended in failure?

President Nixon had a speech prepared for this prospect. Written by William Safire, the unreleased speech titled ‘In Event of Moon Disaster’ is a lyrical, poignant announcement of a would-be Apollo 11 tragedy which begins, “Fate has ordained that the men who went to the moon to explore in peace will stay on the moon to rest in peace.”

Safire explained the realities of what the ‘Moon Disaster’ would actually involve: “If they couldn’t [complete the mission], and there was a good risk that they couldn’t, they would have to be abandoned on the moon, left to die there … the men would have to either starve to death or commit suicide. So, we prepared for that with a speech that I wrote and the President was ready to give that.”

As such, the speech sought to glorify what would have been a miserable, drawn-out fate for the astronauts through images of heroism and humanity: “In ancient days, men looked at stars and saw their heroes in the constellations. In modern times, we do much the same, but our heroes are epic men of flesh and blood.” Safire’s ability to convert tragedy into linguistic beauty adds to the prevalent idea that the astronauts would be leaving a legacy (rather than simply dying).

Space itself is beyond human comprehension, even 50 years later. To compress the distance between the worldly and the stellar through words, as Safire does, creates an unbreakable connection between the astronauts and the rest of mankind: “For every human being who looks up at the moon in the nights to come will know that there is some corner of another world that is forever mankind.”

If it had been too factual or too harsh, mankind’s tentative forays into space could have crumbled and with it the poignant realisation of the microscopic capabilities of man, poisoning a newly hopeful society.

The techniques used to such great effect in this speech-that-never-was go back far beyond modern history to Aristotle and his Three Proofs. The concept suggests that successful persuasion is comprised of credibility (ethos), emotion (pathos) and logic (logos).

Within Nixon’s would-be speech, pathos is achieved by the use of mournful yet reflective imagery, with nods to stars, bodies and memory. Its credibility (ethos) is derived from the authority of the office from which it was given, while the reality for these astronauts – trapped in space, awaiting death – is evoked without evasion. It is perhaps this complementary triangle of rhetoric that cause us to feel such a loss, and to be persuaded in the belief that: “In their exploration, they stirred the people of the world to feel as one; in their sacrifice, they bind more tightly the brotherhood of man.”

It is, after all, merely strings of words that have the capability to shape the world; to start wars and end them, to inspire movements and quell them – or, simply, do absolutely nothing.