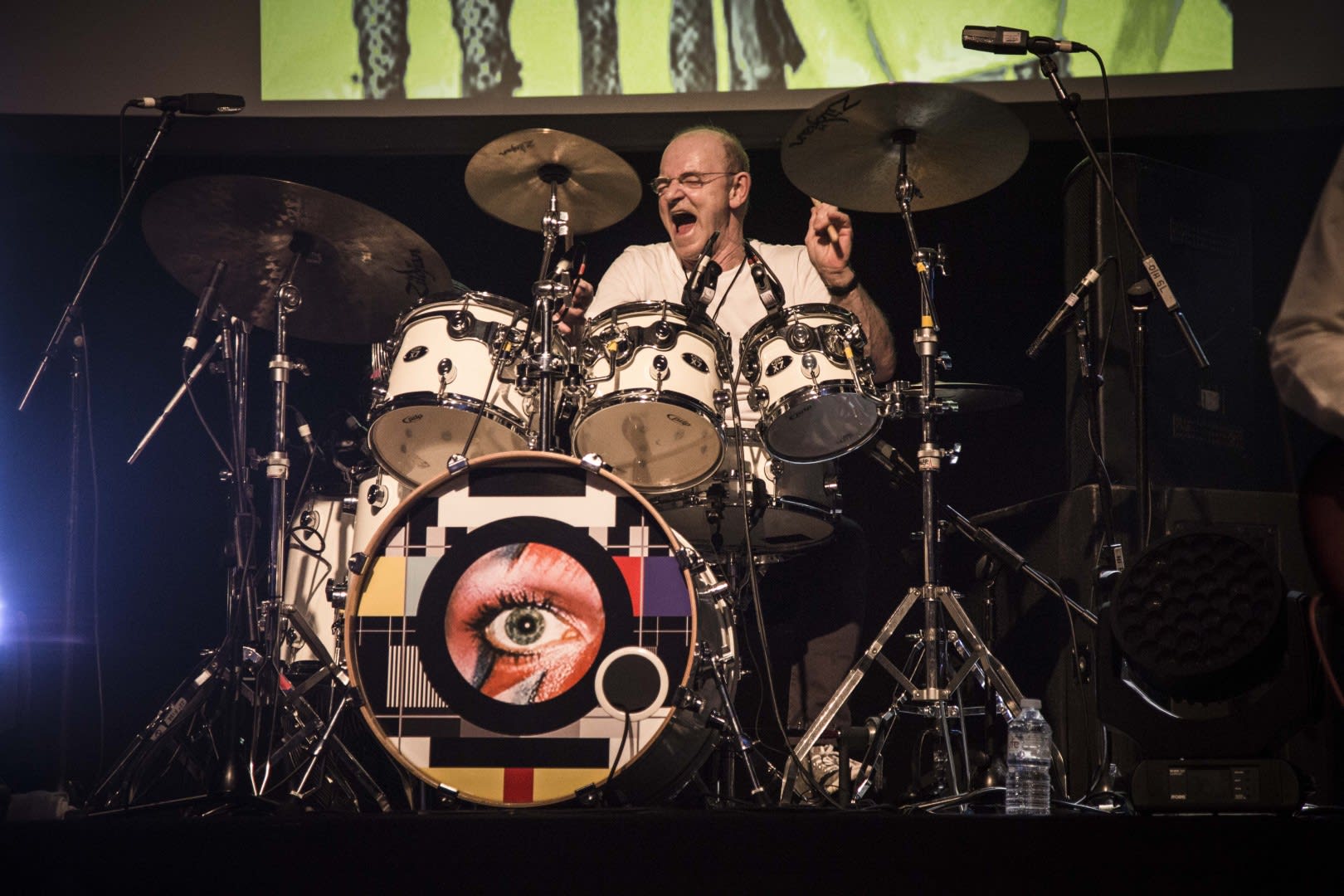

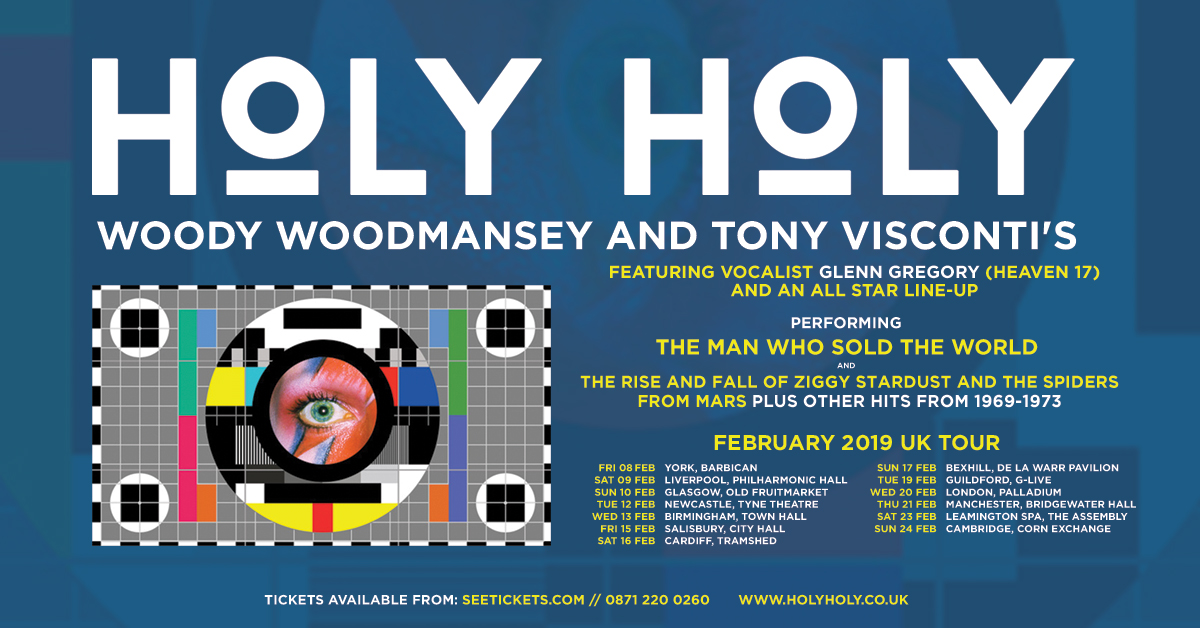

Holy Holy are the authentic sound of David Bowie’s early songs, starring Woody Woodmansey, Bowie’s drummer from 1970-1973, and Tony Visconti, Bowie’s long-time producer and bass player on The Man Who Sold the World. With an all-star band that includes vocals from Heaven 17’s Glenn Gregory, they head out on tour in February, delivering probably the closest thing to a Bowie gig you can get. Here, Woody tells us more about fandom, truth, The Man Who Sold the World, and the great man himself.

70s gig crowds.

There were a lot of sparkly faces with stars and bright clothes – it was like playing in a circus ring. They probably didn't see it, but they were as bright as us sometimes. To some extent in the UK – well, I guess everywhere – we pulled what people would call ‘the freaks’. That went from just ‘rebels’ that hadn't quite found their feet yet, to the real freaks that knew”¯they were freaks. We got them all. I remember – in America somewhere – we were out the back after a concert, having a drink, and we had kind of dressed down a bit. These three guys roller skated up to us with full-length dresses on. They had long hair, they'd sprayed their beards silver and they were wearing makeup and had bangles on. They just stopped in front of us, we looked up, and then one of them just went, “You guys are so weird.” It was surreal they were calling”¯us”¯weird – what can you say to that?

Devotion.

In the 70s we came offstage after a show, ran through security, and got into a limo to the hotel. There would always be a gathering at the hotel that had found out where we were staying, and sometimes we had”¯a bit of a party and invited them in, but most times you didn't really meet the audiences – you didn't do meet and greets and things like that. The degree [of devotion] has only really sunk in from doing meet and greets in the last four years – I don't think even David knew it. Holy Holy were on tour when he passed away and we'd spoken to him from stage on his birthday, and then a day and a half later he was gone. We said, “Okay, we've got to put these meet and greets in, it would be good for the fans.” And you'd meet people who would say, “I've waited nearly 40 years to say that I was going to commit suicide, and I got”¯The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars and it stopped me – I just want to say thank you.” Two brothers came up one night and said, “We got drafted to Vietnam, the only album we took was”¯Ziggy Stardust; we wouldn't have got through it and kept sane if it hadn't have been for that album.”

Writing Spider from Mars: My Life with Bowie.

I had about six publishers approach me and I kept turning it down because I thought David was probably going to cover that period extensively – why would I want to compete against him? Then I found out through the grapevine, and from him, that he was never going to do that. And I noticed there were at least half a dozen books out – it was ridiculous. They were written by people who just had no clue how we recorded, how we toured or what we did. They would just put their opinions down as truth, as though they were there. I went through a few of them going “that’s not true, that never happened, he wasn't there…” The next time I was asked, I said I’d do it, just to put the record straight.

Holy Holy.

It came about purely because the”¯Institute of Contemporary Arts”¯were doing a”¯Bowie Week,”¯showing films and playing albums. They'd sold out the nights, and they asked if I’d come and finish it off with an interview in front of the audience. It wasn't something I'd done before, they talked me into it, I thought I'd either hate it or enjoy it – I enjoyed it. [ICA] also put a band together to play Latitude Festival,”¯with Clem Burke from”¯Blondie, Steve Norman from”¯Spandau Ballet,”¯Bob Geldof's guitarist – known musicians. They said, “Why don't you come to the festival and just play a couple of songs as a guest?” I thought, ‘Yeah that'll be fun actually.’ It was quite surprising to watch a festival audience singing some of the songs that were quite dark; especially from”¯The Man Who Sold the World”¯period – they were singing them like pop music. I never thought I would be stood at the side of the stage watching Clem Burke play all my drum parts. I was going, “Oh no, not that one, I'd love to play that one…” I really did want to walk on and throw him off the drums – but he's a really nice guy so I couldn't do that.

But then he was touring with Blondie, and there were so many requests to do more [Bowie] concerts. They said: “Would you be the drummer in your own band?” I said, “Yeah, as long as I don't have to audition.” And it just built up from there.

I got Tony Visconti involved purely because I wanted to do”¯The Man Who Sold the World, [on which] he was the bass player and producer and I was the drummer. I asked Tony and straight away he said, “Yeah, wherever you're playing Woody, I'll be there.” I was a bit taken aback. I thought it would take me two hours to convince him, because I knew he was busy. He said, “I've done 12 albums with Bowie, and every album we talk about”¯The Man Who Sold the World”¯and how we regret never playing it live. It's always been on my bucket list.”

We actually did a live album at Shepherd's Bush on the first”¯Man Who Sold the World”¯tour Holy Holy did. Tony mixed it and said, “I've got to play this to David.” He said he was just grinning from ear to ear listening to the album, and dancing around the room. He said, “Tony, if we'd have toured that album, my career might have taken a different turn,” and that “it's also nice to hear somebody sing the songs as I intended to sing them.” I just thought wow, that's quite an acknowledgement; that's Glenn Gregory’s singing – he does an amazing job really.

Bowie.

I think before”¯The Man Who Sold the World,”¯he only occasionally did things that he felt were 100%”¯him – that reflected in the success before that time. The Man Who Sold the World”¯opened him up a bit musically, and [got him] into the rock feel he hadn't really been in before. Then after his trip to America, where he’d hung out with Andy Warhol and met Lou Reed and Iggy Pop, we were all listening to The Velvet Underground”¯and Iggy, and the jigsaw pieces started going together. When I first met him, you could see there was talent there and he was determined, but he hadn't quite sorted out the direction songwriting- and image-wise. When it started to come together, he just had this [mentality]: ‘That's what I want to say, and I want to say it like that. It either goes successfully or not, but I have to stick with what I think.’

He was genuinely into lots of different music. It wasn't a surprise, to us anyway, that he went into the funk thing, and he did a bit of soul and then electronica – he was at the forefront of a lot of that stuff. Then he kind of started jumping on the bandwagon a little bit, I thought, when he did drum'n'bass, because it had been out underground before then – but he grabbed that because he liked it. He had that ability to look at an area and go, “Oh, there's something about that particular genre that fits what I'm thinking.” And he would learn everything he could about that particular area.

He never stood still. I always admired the fact that he could go, “Okay, I've got a formula for hit singles and for doing albums that are successful. But I'm not going to just stick with that formula, I'm going to throw that out the window and apply what I've learned to a new genre.” Not many bands or artists are able to do that. He had the courage and integrity. I always thought he could write a hit single in any genre that he wanted at any time he wanted, he just didn't always want to. If having a hit single didn't fit his concept, he wasn't that bothered about writing one.

Holy Holy play Birmingham Town Hall 13 February, and London Palladium 20 February.